Just as Helen possessed the face that launched a thousand ships, Orpheus, the legendary musician and poet, charmed a thousand hearts with his music.

“Orpheus with his luted made trees

And mountain tops that freeze

Bow themselves when he did sing:

To his music plants and flowers

Even sprung; as sun and showers

There had made a lasting spring.

Every thing that heard him play,

Even the billows of the sea,

Hung their heads and then lay by.

In sweet music is such art,

Killing care and grief of heart

Fall asleep, or hearing, die.” (Shakespeare, Orpheus)

Alas, this ability to kill grief, in true Ancient Greek fashion of the cruelty of fate, did not extend to himself or his beloved. Upon losing his new wife, the beautiful and graceful Eurydice, to a nest of vipers, Orpheus ventured into the Underworld in a desperate attempt to get her back. His music charmed the coldest and darkest of hearts in Hades, who agreed to relinquish Eurydice from his realm upon one condition: that Orpheus did not look at her until reaching the sunlit earth. Unable to hear Eurydice’s footsteps behind him, Orpheus convinced himself that the gods had fooled him, as they so often did in their powerful and playful ways. Eurydice was in fact with him, although in the shape of a shade, as she was returning into the light to become a full woman again. Tragedy strikes, when only a few feet away from the exit, Orpheus loses his faith and turns to see Eurydice, losing her forever to Hades. The story has enchanted the imagination for thousands of years as such moving talent has been defeated, and such heroic love snatched away.

Roelandt Savery, Orpheus Charming the Animals with His Music (1610)

Northern paintings haven been, for centuries, unjustly crystallised into many’s imagination as gloomy-coloured; so much so that Rembrandt’s painting has been erroneously named The Night Watch- age has been unkind; it had originally stunned with its bright sunlight. The delight in exuberant colours and exotic species (Rembrandt had a stuffed crocodile amongst his personal collection) has been given full expression in the life-long wanderer Savery’s painting. The elephant raises its trunk in symphony with the exalting tunes as the often beastly and savage lion stands transfixed. All in nature comes, bewitched and besotted.

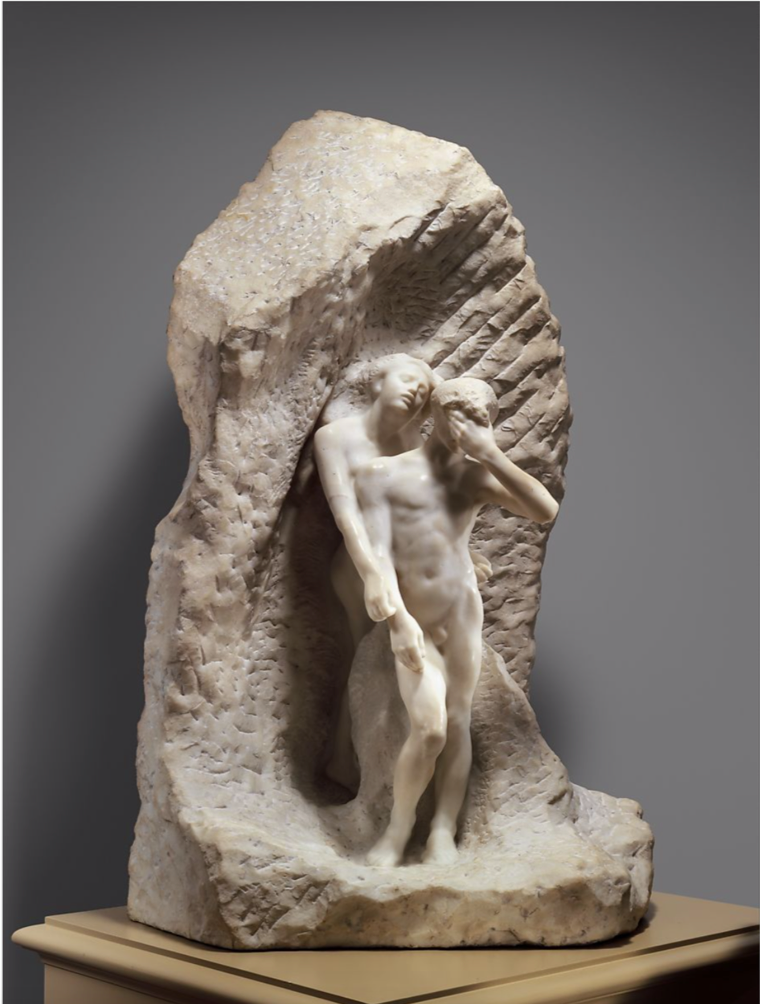

Rodin, Orpheus and Eurydice (1893)

Eurydice, in her ghoulish, spectral form, floats behind Orpheus, reaching the underworld’s entrance. Orpheus, in a fateful moment, hesitates and loses confidence. An instant later, he will glimpse her, and Eurydice will vanish forever. Rodin captures a moment foreboding infinite tragedy. Yet both figures seem to levitate, forever in floating motion. One lingers gluttonously at this pause, wishing it would last forever.

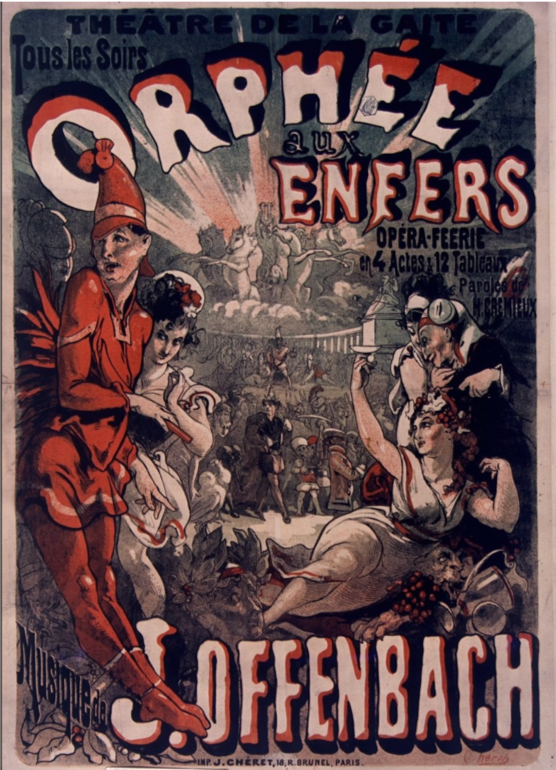

Jacques Offenbach, Orpheus in the Underworld (1874 production in Paris)

Ever keen to mock, the Parisian stage turned the ancient legend into political satire. Liberally alluding to the lechery of Napoleon III’s court, Offenbach found his way out of financial difficulties with this box office hit by lampooning the ancient legend. In this, Orpheus is no longer the son of Apollo, but a buffoon of a rustic violin teacher, who is only too glad to have his wife abducted to the underworld. Alas, public opinion bullied him into trying to rescue Eurydice. Here, the gods are despicable, and promiscuity runs ripe in the divine and mortal alike.

Christoph Gluck, Orfeo ed Euridice (1762)

Hermes may have invented the lyre that was to enthrall generations in the Classical world and the Middle Ages, and gifted Apollo with the divine patronage of music; but Orpheus, the ultimate musician, perfected it. Gluck bid farewell to the overly complex music of opera seria and succeeded with a heart-rending score of sublime simplicity in both the music and drama. The score went on to influence major German operas subsequently, with variations on its plot- the underground rescue mission in which the hero is compelled to control and conceal his emotions- finding their ways in works such as Mozart’s The Magic Flute and Wagner’s Das Rheingold. Gluck concentrates on the madness and folly of love–eager to retrieve Eurydice and forbidden by the gods to either look at her or tell her what is going on (the latter condition an invention of Gluck’s), Orpheus encounters a panicked Eurydice who takes his refusal to even look at her as a sign that he no longer loved her. Orpheus eventually gives in to Eurydice’s mournful cries in an outburst of desire, only to lose her forever. The gods, cruel and omniscient as they are, know the fragility of love only too well. The lover is always greedy and made insecure by the tiniest’s coldness on the part of their beloved. Eurydice is depicted as a silly girl obsessed in love, and Orpheus, although less silly, cannot toughen his resolve in the face of her beseeching sorrow. Gluck poetically encapsulated Ovid’s verdict, “his sole fault was to love her.” There is truth in Plato’s worry that music is the most infectious form of communication, so much so that the political philosopher proposed to ban it in the training of his ideal city guardians. Here, one gets a taste of perhaps what Savery’s lucky animals got to enjoy- the supreme force of music penetrating every sinew in one’s body.

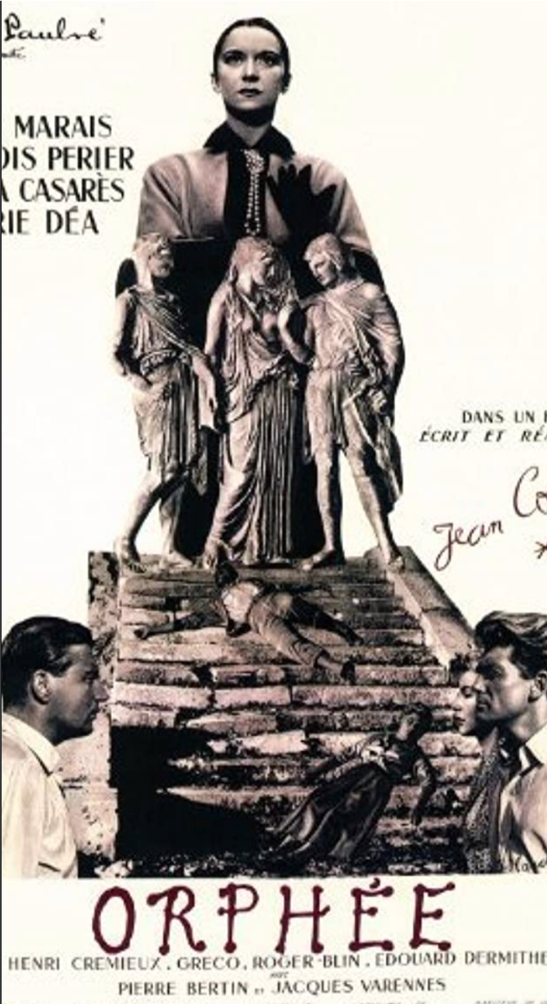

Jacques Cocteau, Orphée (1950)

The austerity in post-WWII Europe proves no hindrance to an artist’s creativity, at least, not for a virtuoso such as Cocteau. With an eclectic career spanning areas such as poetry, plays and visual art, Cocteau reimagines the vivacious world of gods and immortals. The beautiful Death falls in love with the terse, yet poetically gifted Orpheus. She secretly watches him in his sleep and even taking Eurydice just to create an opportune to meet Orpheus again. The story is just rich with deceit, the omnipotence and cruelty of the gods and destructive romance as any Ancient Greek tale. Here, the tragedy is that of an underling of the gods unable to pursue her romantic love and eventually sacrificing herself for it. Cocteau plays with the leitmotif of mirrors as gateways between earth and the underworld.

Igor Stravinsky, Orpheus (1948 score, picture of 2012 New York City Ballet performance)

Stravinsky composed the three tableaux for American choreographer George Balanchine’s neo-classical ballet. The score remains the most melodic of Stravinsky’s, profuse with usage of woodwinds. Stravinsky is perhaps best-known for his vibrant The Rite of Spring, as a scene in Yes, Prime Minister depicts the adviser remarking to the newly elected PM that if he wished to project change and hope in his first televised address, Stravinsky would be the go-to composer. However, in this, Stravinsky does completely without a percussion section, using predominately quite dynamics. He also gave an important role for the harp, paying tribute to Orpheus’ association to the lyre.

Céline Sciamma, Portrait of a Lady on Fire (2019)

Sciamma’s lesbian period drama employs the myth of Orpheus to re-centre the female gaze. The two lovers know their time is soon up and the idea of a reunion far-fetched. The tormented lovers bid farewell to each other through a reinterpretation of Ovid’s tale–Orpheus is not mad or irrational, he chooses the memory of Eurydice. Perhaps Eurydice senses it, too–she calls out to Orpheus to glance back, retaining the souvenir of their love.