This interview was conducted on 18/5/2021.

The latest escalation in the decades-long state of tension between Israel and Palestine has seen at least 230 Palestinians, including 65 children, killed over 11 days by rocket fire from Israel. Over 50,000 Palestinians have been displaced. In the same period 12 Israelis, including two children, have been killed. Israel’s ‘Iron Dome’ defense system has prevented many rockets fired by Hamas from reaching their target.

After mounting international pressure Hamas and Israel agreed to a ceasefire commencing at 23:00 GMT on May 20th (2:00 on May 21st local time). President Biden has hailed the moment as a “genuine opportunity to make progress”. But how can diplomats solve a crisis which has been ongoing for over 70 years?

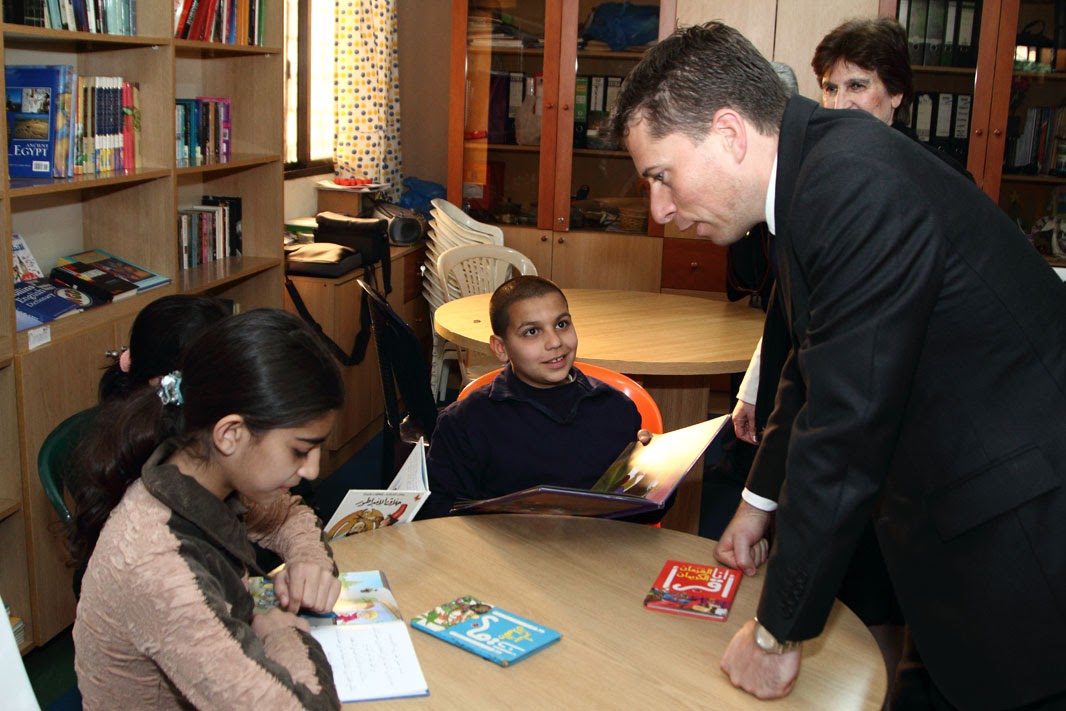

Tom Fletcher began his diplomatic career in Kenya and France, before serving as a foreign policy advisor to Prime Ministers Gordon Brown, Tony Blair, and David Cameron. In 2011, he became the youngest senior British Ambassador in 200 years when he took up the post of Ambassador to Lebanon. In 2020, he took up the post of Principal at Hertford College, where he read Modern History.

Cherwell: Arguably, this is one of the most difficult geopolitical challenges in the world to solve. How have we got here?

TF: “It’s a great question. If it was easy we’d have done it a long time ago. Very smart diplomats and peacemakers have been working on this for decades since 1948. I still think that at its root there is a simplicity to this, which is that you need two states: a state of Israel and a state of Palestine, where the rights of Israelis and Palestinians are considered equally. But it’s much harder to actually deliver that.”

2021 marks 73 years since the Nakba, which saw Palestinians forced to leave their homes. Has the fact this crisis has continued for decades made it harder to resolve?

“There have been moments when a two-state solution felt much more possible. I was actually in Israel-Palestine in 1994 when there was a sense of things moving in the right direction. The populations themselves were more optimistic; Yasser Arafat came back and there was this sense that there was a deal to be made, which was basically land-for-peace. The problem is the politics. The politics on one side or the other doesn’t quite work so often.”

President Biden has called for a ceasefire, despite the United States recently vetoing a UN Security Council statement calling for just that. What is the US trying to do at the moment?

“The good news is that, unlike Donald Trump, Joe Biden isn’t fanning the flames. I’ve been saying I don’t think he’s doing enough yet to put them out. But, I think we can be encouraged that Joe Biden, Anthony Blinken and Jake Sullivan are people with huge amounts of national security experience dealing with Israel-Palestine. They know the leaders very well.

“I feel more confident that they are putting that pressure on behind the scenes. I know from talking to people at the White House that there is a lot of behind-the-scenes pressure for a ceasefire. It’s great that they’re now calling for that publicly.

“Often, the tactic is that America will blunt criticism of Israel in public, in order to put more pressure on them in private. They’ll say to Number 10 or the Elyseé: ‘Don’t push for a [UN Security Council] resolution on this. Give us more time. We need more time to convince the Israelis to stop.’ That’s the normal dynamic at these moments.”

Have the actions of the Trump administration exacerbated the situation?

“They have. There was obviously no pressure during that time for Israel and Palestine to actually come to the peace table in a serious way. Almost everything that Donald Trump did made it harder to come to the table. For example, the Americans knew that moving the embassy to Jerusalem was very provocative for many in the region, not just the Palestinians.

“Also, in that period there was a sense that Netenyahu knew he could expand settlements as much as he wanted, and there would be no criticism. That really did build much of the pressure that has led to this point.”

What steps can the UK government take to help calm the situation?

“The most important thing the UK can do is push in public and in private for a ceasefire and for real diplomacy towards a two-state solution. Importantly, the UK – even with aid cuts – is still a big aid donor and has an important voice in trying to get humanitarian access. At the moment, Israel is blocking that access. It’s vital to get in there: hospitals and schools have been damaged. We’ve got to get in and start to rebuild.

“The UK does have ways to put pressure on the parties on the ground to get them back to the negotiating table. I wouldn’t want to be too prescriptive about what those are, because it’s quite good to go into a negotiating room and have those options.”

According to UNICEF, there are 192,000 Palestinian refugees in Lebanon. When you were the Ambassador to Lebanon, how aware of the situation in Israel-Palestine did you have to be?

“Many of the Palestinian refugees who fled Israel and Palestine in 1948 and 1967, many driven from their homes, have become double or treble refugees. They had to flee again because of the civil war in Lebanon. In some cases, they fled to Syria, and then became refugees again. So you have that trauma going down through generations.

“It was often a dynamic we had to be very aware of. When there was violence across the Israel-Gaza border, it was often likely that rockets would come across the Lebanon-Israel border as well. There was always a danger that Israel would smash up the south of Lebanon, or that Hezbollah would fire rockets at the north of Israel at civilians. We were always we’d move very fast with the UN to try and de-escalate those situations.

“It was also a big dynamic because Hezbollah was the most powerful political group in Lebanon, when I was there. Of course, Israel was very unhappy about that. Many of us were very unhappy about the power Hezbollah had. But they were a political actor in their own right. As embassies, that was a difficult dynamic for us.

“I used to always say about the kinds of challenges Lebanon faces around coexistence and living together despite our differences; if we can’t crack those in Lebanon, we’ll face them closer to home as well. I think that in the five years since I’ve left Lebanon, you can see the way those arguments are now playing out in our own society.”

What lessons have you learned from working with the Lebanese government, which is divided along sectarian lines, to promote stability and human rights? How can these lessons be applied to the Israel-Palestine crisis?

“I think you have to recognise the historical roots of much of this. Part of the work of diplomacy, and of being a good ancestor, is to think about healing the wounds of history. What are the grievances and judgements that we inherit that we should pass on? And, what are the grievances and injustices and hatreds that we must not pass on? I think working that out is the most important work of an ancestor.

“Education is also really important. For me, education is upstream diplomacy. It’s why I’m now in Oxford. A project we did in Lebanon was to work with the different religious groups on ‘how do you teach people from other groups about your religion?’. What we found was that in most schools you were taught purely by people from your own religious group. They would say: ‘the people down the road that look different, or worship a different god, or worship in a different way, they hate us. So we have to hate them,’. We got the 19 religious groups together, to try and get them to find a common way of teaching about each other. It was really complex, but it’s really important.

“I think that the more Israelis learn about Palestinians, and Palestinians learn about Israelis, the more people-to-people contact there is, more people can understand they have more in common than what divides us.”

You have repeatedly said that you are both Pro-Palestinian and Pro-Israeli. That’s a stance which leads to accusations of bothsidesism and downplaying the suffering of Palestinians, or is compared to saying ‘All Lives Matter’ at a Black Lives Matter parade. Considering this level of polarisation, how do we make room for nuance?

“One way we can start is to get away from the sort of statements we make as governments. I’ve written these statements for years, so this is kind of mea culpa. We tend to write statements saying: ‘Israel deserves security, and Israel has a right to self-defence. Palestinians deserves to be free from discrimination, and to be able to improve their livelihoods,’. Actually, Israel and the Palestinians both deserve security. They both deserve dignity. So we start to identify things which are clearly issues of dignity, equality and human rights. The Palestinians have as much right to all those things as Israelis. Rather than saying ‘one side deserves this, the other deserves that’, we recognise that there is a common framework there.

“We also have to be honest that there is a massive imbalance. Israel has disproportionate strength, and uses it in disproportionate ways.”

How do we bring a sense of proportion into this discussion?

“Part of it is about calling out what is disproportionate. ‘Proportionate’ is one of those slightly measly diplomatic words. We say: ‘We call upon all parties to act in a proportionate way,’. Great, we do! But what does that actually mean in practice?

“Do we think it is proportionate to take down the building with international media offices in? I haven’t seen a real explanation for why it was targeted, apart from chatter from the Israeli Defence Force saying it was some kind of Hamas cell. Again, it comes back to the nature of proportionality. What’s the evidence for that? Do we collectively think that justifies taking out a building in that way?

“Do we think it’s proportionate if the home of a Hamas commander is in one neighbourhood, to hit that neighbourhood. I think there’s a legitimate argument to be had, there. For me, I don’t regard those things as proportionate. I think we should call them out as disproportionate. I think doing that gets us beyond the simple ‘Ah, but Israel has a right to self-defence’ or ‘Ah, but the Palestinians have a right to fire those rockets’ into a more nuanced conversation.”

Over the weekend I was speaking to a lot of protesters, many of whom were Palestinian. They told me it was important to ‘change the narrative’ around the crisis. How do we bring the sense of proportion you have already discussed into narratives in the media or governments?

“I think some of the points I’ve made about language are part of that. We should condemn attacks on civilians no matter where they come from, rather than condemning them from one side and saying ‘we’re concerned’ about those from the other side. I think there are subtleties there which show we’re not equally concerned about both sides.

“So much of this comes back to a two-state solution. We have to show that we don’t just care about this situation when there’s a flare-up. When it does calm down, as it will do, we have to show we are going to get that state of Palestine, and to end the discrimination of the checkpoints and the economic chokehold on Gaza. We’ve got to be talking about that as much as these flare-ups, rather than thinking ‘well that’s okay now, we can go back to normal’ because the status quo isn’t fair, because the occupied Palestinian Territories are still occupied.”

How do we bring the Israeli government, Hamas, and the Palestinian National Authority together for negotiations?

“I think a starting point has to be an unequivocal recognition of Israel’s right to exist, and of Palestine’s right to exist. Suggestions that we can go back to a time when you could deny either of those things are really unhelpful.

“I think ultimately, we probably aren’t at a point where there is a quick fix now, even though we know what the deal looks like. Most moderates in Israel and Palestine know what the deal looks like. Most diplomats, including in the White House, know what the deal looks like. We almost got there in the past.

“We’re not going to suddenly have a peace conference, and it will all be okay. That’s a delusion. We’re going to need to do this more incrementally, and that starts with rebuilding trust. We have to show that we can bring back opportunity and dignity to the Palestinians. We need much more in the way of people-to-people contact between Israeli and Palestinian civilians, which gets past their two governments.

“The problem is that, at the moment, the hardliners around Netenyahu and around Hamas are getting stronger. They are unpopular, and were becoming more unpopular. Now, because of this crisis, they’re seeing an opportunity to regain their foothold.”

Does this conflict play into their hands?

“They certainly calculate that it does. They both draw oxygen from each other. It’s a terrible situation to be in, when that is the case. But, we’ve got a hardline Israeli government and a hardline government in Gaza. As long as space for moderates is choked off, it’s going to be really difficult to make any progress.”

When people talk about the conflict between the Israeli government and Hamas, the West Bank – which is not administered by Hamas – is often left out of the conversation. Considering that the majority of the West Bank lies under Israeli control, and Palestinians face restrictions on their movement within the region, what role does the West Bank play in resolving the crisis?

“The core of the solution will be that the Palestinian state would be in the West Bank, with its capital in East Jerusalem. That’s been the British position, the International position, and even the American position for decades. The West Bank has to be key to that. But that means we need to see an end to the expansion of settlements, because at the moment a Palestinian state will not be viable if the continued development of settlements choaks off the space available.”

What impact could this crisis have in the Middle East beyond Israel and Palestine?

“It makes it much harder to make progress on the wider normalisation of relations with Israel. You’ve had countries across the region recognising Israel’s right to exist and building diplomatic ties. That doesn’t mean they won’t and shouldn’t be very critical of Israel when it discriminates against Palestinians, builds settlements, and levels areas of Gaza. But it is positive that there is a wider acceptance [of Israel’s right to exist], and that’s part of the answer. I think it’s important that there’s recognition that you can’t have one without the other: normalisation with Israel needs to be accompanied by normalisation with the Palestinians, too. I worry that the violence on the ground and inside the Al-Aqsa mosque, and the forced evictions have settled back some of the wider efforts to build peace in the region.

“They also strengthen the rhetoric of extremists across the region. They give Iran a sense of cause. Iran loves to claim it defends the Palestinian cause, while it fights to the last Palestinian. Extremist groups will draw oxygen from this, from footage of Israeli soldiers inside a mosque during Ramadan. These are quite counterproductive images.”

There’s another element to this conflict, and indeed many others in the twenty-first century, which is an information war on social media. Considering the power of viral posts to shape opinion and spread a message, has social media turned us all into diplomats?

“I think it has. In the book I wrote, I ended with a chapter called Citizen Diplomats, because we need everyone to start thinking like diplomats. That doesn’t mean we all need to walk around speaking in platitudes about proportionality and ceasefires and so on. But it does mean we need to start thinking critically and have to be more discerning about what we read, what we sign, what we share, and the ways in which our actions and words can be a part of the solution, or part of the problem.

“In Lebanon, whenever a bomb went off I used to say the things we needed to do as individuals was to pause for breath, not to rush to judgement about who was behind it, and then to reach out to someone on the other side. These aren’t complicated things. They should be basic human instincts, and yet we don’t always do them.

“On an issue like this, it’s so sensitive and delicate. Getting the words wrong really matters. What I’m trying to set out is actually what the international humanitarian law is. It’s not my view. It’s actually what the international humanitarian legal approach is. I think the more people can go back to the facts, seek them out, and then call out the more toxic media and images, the better. The media has a really key part to play in this.”

Featured Image: Ministerie van Buitenlandse/CC BY-SA 2.0 via flickr.com