A Cherwell investigation reveals the vast disparities in rent prices across Oxford colleges, with a 50% difference in modal weekly rent between Keble, the cheapest college, and Pembroke, the most expensive. Whilst a Pembroke undergraduate could expect to pay £232.74, the most common weekly charge for a student at Keble was £155.61.

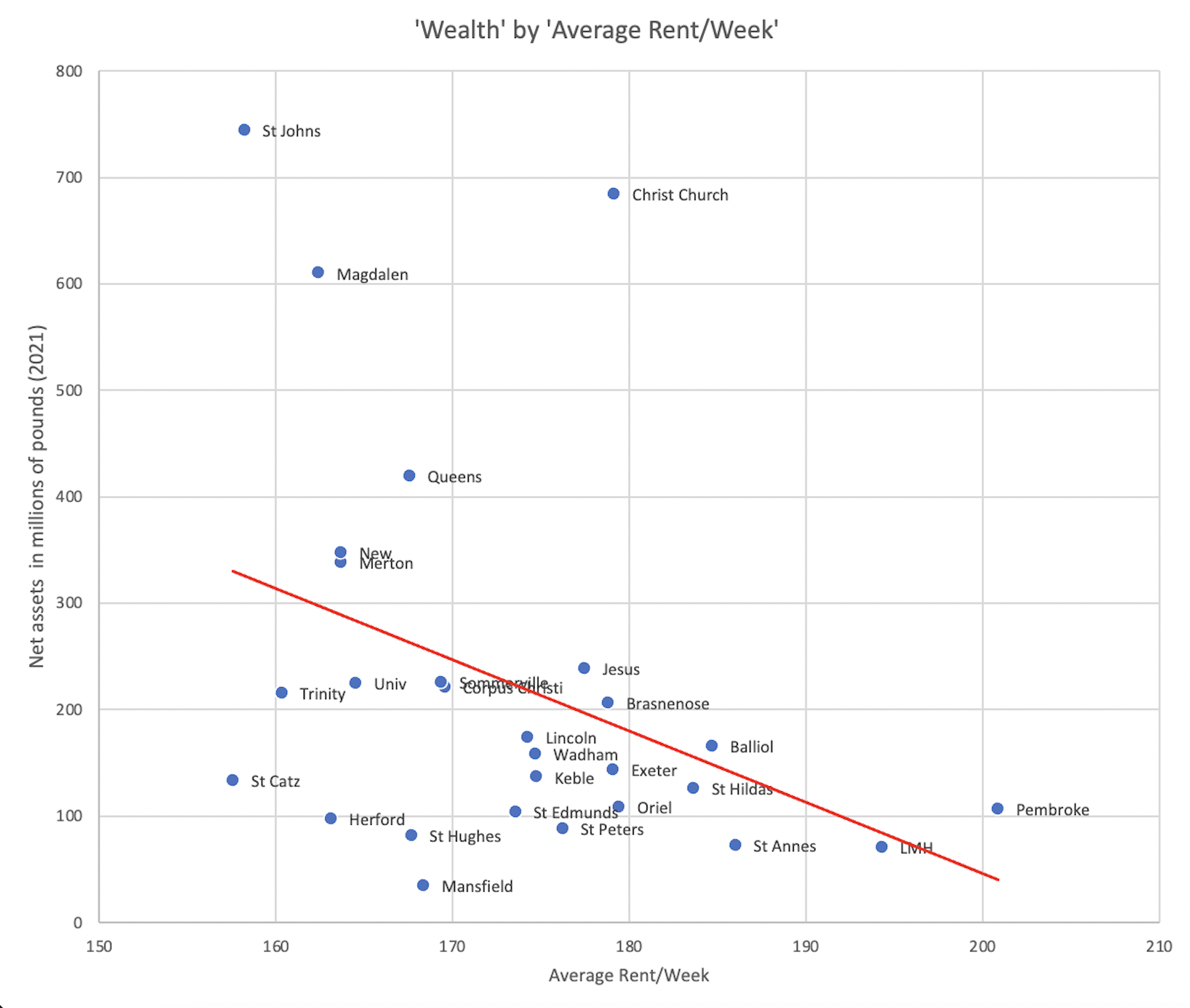

Whilst an Oxford student may expect annual living costs to be lower due to the 8-week terms, the affordability of city life is highly dependent on college. Cherwell finds that, based on average weekly rent for short lease periods, wealthier colleges tended to charge the lowest amount of rent, with the large disparities in college wealth dramatically affecting student life.

Amongst the 10 wealthiest colleges, assessed by net assets, seven of these were among the colleges ranking the lowest average rent, including St Johns, Magdalen, and Queens. By contrast, among the 10 least wealthy colleges, five of these fall within the highest 10 average rent prices, with colleges such as Pembroke, Mansfield, and Lady Margaret Hall at the top of the list.

Magdalen college, the third richest college, provides the fourth cheapest average accommodation costs amongst Oxford colleges. By contrast, Lady Margaret Hall is the second poorest college and equally the second most expensive college accommodation, following Pembroke.

Furthermore, inflation is set to see rent prices increase further, amplifying the gaps between colleges. St Catherine’s College has proposed an increase of 11.8% in rent and hall prices, in line with the average 9% inflation rate of the UK.

Currently, the termly rent at Pembroke, the most expensive college, varies between £1153 and £2245 termly, with an additional £432 annual utility charge. The college has just announced its price increases for the next academic year, with an 8.68% increase on rent, and a 22.5% increase in utility charges.

However, as the seventh-poorest college by net assets, Pembroke often has had little choice. In 2002, a tape obtained by the Sunday Times caught a senior fellow, Reverend John Platt, admitting that the college offered places for money because they were ‘poor as shit’.

The most common pricing band for on-site accommodation currently stands at £1776, but from next year will be upped to £2010.13 (excluding the utility charge). The rooms in the highest price brackets will reach up to £43.02 a night, with an eye watering total of £7614.54 a year.

St Johns, on the other hand, notoriously the wealthiest Oxford college, has managed to keep the cost of living down. Rent prices at St Johns are one of the cheapest across Oxford – the prices range from £987.74 to £1161.74 per term, with an additional £232 termly charge for services.

Among the disparities between colleges, this highlights the starkest one. There is over a 71% difference between the highest price bands of St Johns, the wealthiest, and Pembroke, the seventh poorest.

This “college lottery” can vastly affect student life and academic performance. A second-year student from Pembroke told Cherwell: “At Pembroke, I am constantly reluctant to spend much extra money in the knowledge that my rent and obligatory (very expensive) hall meal costs have already subsumed much of my student loan.

This can be stressful because it means extensively planning money-saving options for food and other necessities I need to buy in Oxford, as well as extras like social events, in an intense environment that doesn’t give much free time for such planning.”

Pembroke told Cherwell: “We are aware of the difficulties facing many of our students … and will be launching an enhanced student financial support fund next week in response to these challenges.”

The college disparities do not just affect the extent of support that students receive for housing. A Magdalen undergraduate told Cherwell about the abundance of financial support available: “From the first day on arriving at Magdalen I was struck by the generosity of the financial support offer. This began with a universal book grant of £150, an explanation of the incredibly generous travel grant and student support fund, as well as individual support. After experiencing health problems in my first year, the college has paid for taxis from doctors’ appointments that have finished in the evenings in London without me even asking, and even covered the cost of other private healthcare.”

The disparities in cost-of-living expenses are further exacerbated by utility charges or the cost of eating in hall. Pembroke, Mansfield and Harris Manchester are amongst colleges in which hall pre-payment is compulsory. In Pembroke for example, a termly £344.76 charge is taken out for first year for undergraduates which provides only one meal token a day.

This translates into over £1000 over the course of the year, with no ability for credit to be carried over to the following term for tokens which have not been redeemed.

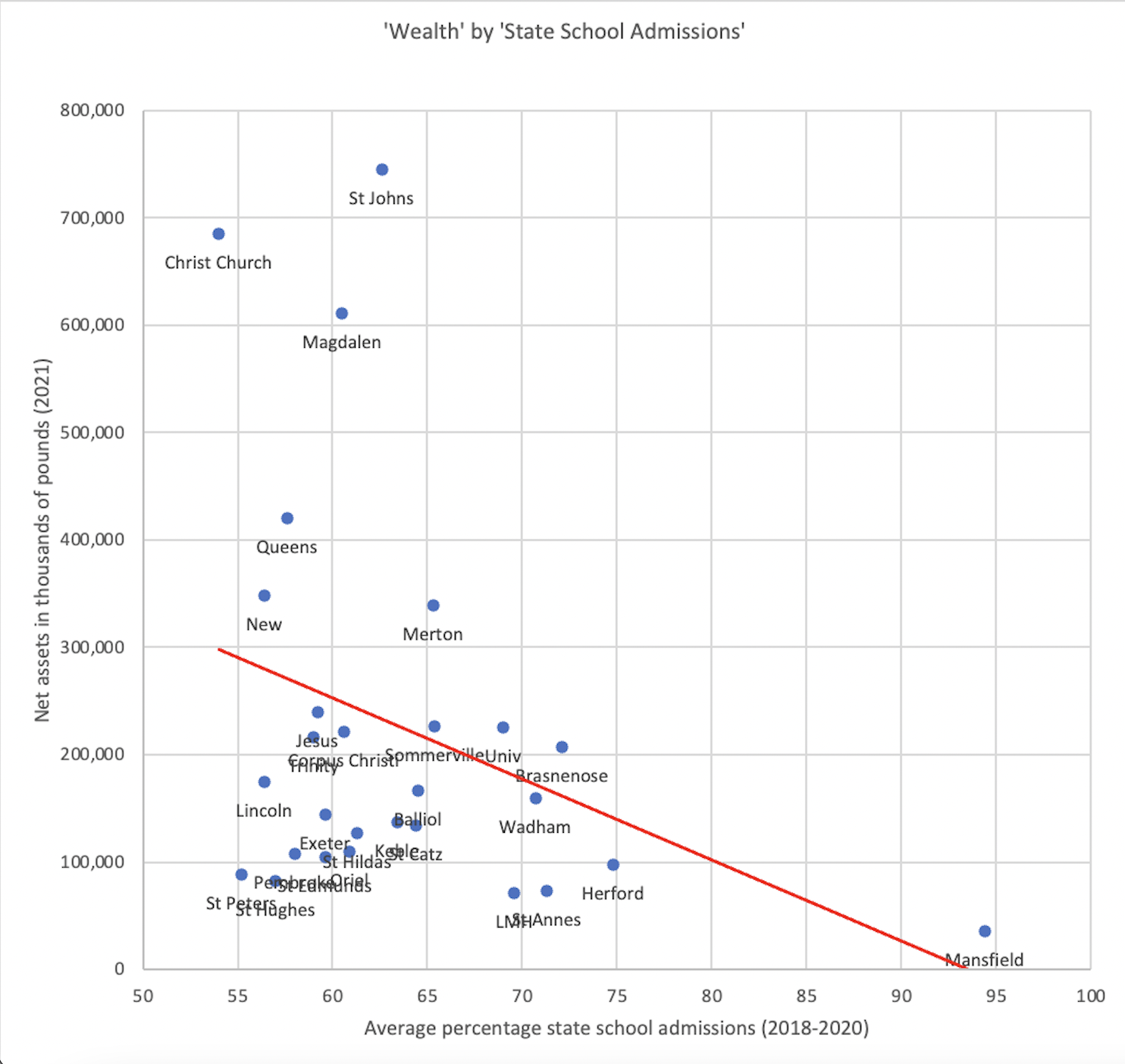

There is also evidence to suggest that colleges with the lowest cost of living also admit fewer state school students. Queens, a college nearly 12 times wealthier than Mansfield, has a state school intake of 63.6%, whereas Mansfield has a whopping 94% of students coming from state schools for entry in 2022.

Mansfield accommodation stands at a uniform fee of £1599 a term, plus a compulsory £140 meal deposit. On the contrary, Queens college charges a standard rate of £1396 per term – a compulsory charge of 20% more per term.

A first year undergraduate from Mansfield told Cherwell: “I am really concerned by the amount of colleges that have announced significant rent hikes and worry what me and my friends will do if this happens at Mansfield. We have already noticed increased difficulty affording living in Oxford, especially throughout this term. Money worries are a constant source of additional and unnecessary stress for us.”

It has been previously mentioned to us by staff that the reason why, despite taking the most percentage of state school students and a higher proportion of students from lower socio-economic backgrounds, Mansfield have higher than average rents is because richer colleges that subsidise them dictate as conditions of funding that rent must be charged at such high rates.”

Christ Church, the second wealthiest college, has the second-lowest percentage of state school admissions, with the figure standing at 55.9%. Whilst the average rent at Christ Church is not within the lowest third, the financial help available is much more generous than the average college. For students with a household income under £16,000, rent is decreased by 50%, whereas students from a household income under £42,875 have their rent decreased by 25%. With a 25% reduction in average rent prices, this leaves Christ Church with by far the cheapest rent of any Oxford colleges.

A rent reduction scheme as the one in Christ Church would largely benefit students from lower-income backgrounds, who more often than not will come from state schools. This indicates how the unequal distribution of wealth across colleges affects the extent to which colleges may provide their students with financial support.

A recent Cherwell report highlighted the link between the wealth of colleges and the performance of students in exams, highlighted in the Norrington Table. The five highest-performing Oxford colleges are also some of the oldest and wealthiest, whereas the colleges at the bottom of the table are considered some of the poorer colleges.

President of the SU, Anvee Bhutani, told Cherwell: “The University does operate JRAM (joint resource allocation mechanism) as a great equaliser to redistribute college wealth but far greater care can be given to ensuring that basic living provisions and costs are similar across colleges.”

Despite the reallocation, it is clear that the college affects every aspect of the student experience. For some, college means access to a rich history, generous financial support and high-level academic support. For others, limited college resources mean rent and hall are just another barrier to an accessible University.

Image Credit: Izzie Alexandrou