CW: Eating disorders, racism, body dysmorphia, references to sexual violence.

Before I begin, I’d like to say thank you to all students that interacted with the forms and polls that were released to gather information for this article. To those of you that are struggling with the issues addressed in this article, please seek help from your college welfare supporters or the University’s welfare service. The appropriate contact details are below.

Charlie’s Angels (2000). A film made from an old-school TV show about gorgeous women spies. What’s the tactic? To take advantage of the fact that men are unsuspecting of beautiful women, making them the perfect spies. Whilst this nurtured an adoration for films and was somewhat empowering for young Sahar, watching it recently, I’ve realised that this is a prime example of pretty privilege. Yes, I’m basing this article off of a cheesy 2000s film that was probably my queer awakening, however, it doesn’t remove from the fact that pretty privilege not only exists but has a deep-seated place in Oxford. Growing up with films like this in conjunction with ideas of what it was to be “pretty” or conventionally attractive – and more the fact that this was not what I looked like – I was taught that pretty privilege was just the way that the world works. This didn’t change when I matriculated, even though my relationship with my appearance improved, and I would come to realise, especially in a context where I was expected to be more outgoing, that there were moments in which I would be overlooked in the “attraction” department.

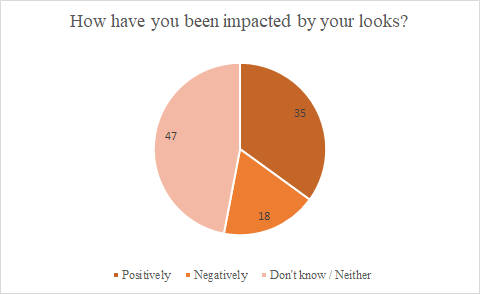

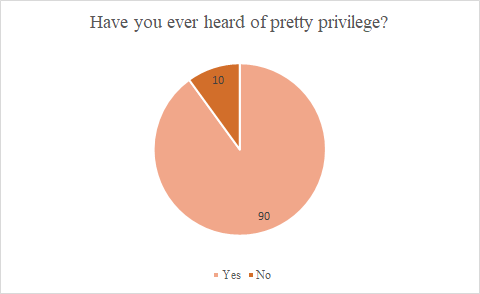

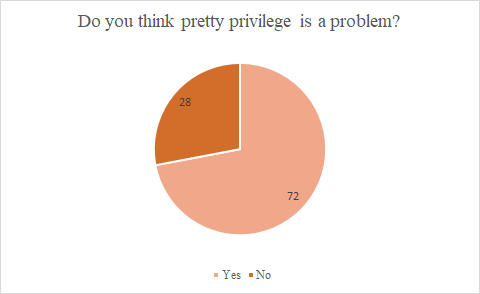

I started writing this article as part of an exploration as to whether anyone else felt like this as well. It turned into a revelation about how prevalent pretty privilege is at Oxford. 70% of people that responded to our Instagram poll recognised that pretty privilege is a problem and 34% even acknowledged that they’d been positively affected by it. It’s safe to say that most people can at least come up with a definition for it:

“For me, pretty privilege means greater freedom and social opportunities”

“Pretty privileged to me is being treated like you’re worth more than others, just because of appearances”

I think you get it.

Pretty privilege has a diverse impact on Oxford students, not only in the way that it is advantageous for certain people but also in how very many students oppressively feel it in their lives here. Of course, where most people feel it most is in the dating scene:

“I got into my first and only proper relationship at the big age of 19. I never thought I was pretty enough to have a partner.”

Before I carry on, I want to linger on this statement for a minute. A lot of the time, you’ll hear an Oxford student say that they never dated or were in a relationship before university because they were working or studying. Therefore, when we get to Oxford (especially in Michaelmas term of first year), the overwhelming pressure to get with the person to your left can be incredibly terrifying when you haven’t, first, addressed possible factors that will have knocked your confidence in the dating scene that can be attributed to pretty privilege. Now, I’m not saying that everyone who has said this has the same experience, but I also want us to realise that it is possible for these things to come hand in hand. One response, even without naming pretty privilege, showed how this was strikingly present in dating apps:

“Once, I was added to a group chat of unknown numbers where they made fun of my appearance… There’s a reason I don’t use dating apps. I don’t know what pretty privilege is, but it’s probably avoiding that harassment.”

Whilst dating apps can be used to facilitate healthy and long-term relationships and romantic interactions, I don’t think we acknowledge how often they facilitate pretty privilege when someone is only deciding to go on a date with you based on your appearance. After a conversation with a friend, we also realised that the reason we felt so insecure on dating apps was because we didn’t fit into the cookie-cutter image that appealed to most others on it. These people shared this experience:

“I feel like people overlook me, before they get to know me”

“There are moments that you remember yourself, and you realise that you’re not attractive here. This is not your space to be loved or appreciated for the way you look.”

“it just feels like men often don’t want a woman who is bigger than them – they want someone small and slim and kind of dainty?”

Dating apps, completely based around pictures with “a few questions” to keep up the pretence of connecting people through their personalities, exacerbate so many issues around body image such as body dysmorphia and possibly even eating disorders – especially as a woman because of the way that the heterosexual dating scene expects women to fit a certain image for the sake of men. A couple of interviewees who identified as queer described how pretty privilege seems to exist less frequently in the LGBTQ+ scene at Oxford; “embracing the queerness” of their appearances – in the way that they didn’t fit into the male gaze – allowed them to become more confident with themselves and alleviated the pressures to look a certain way. However, unfortunately, the queer scene is not immune to the influence of pretty privilege. This was a heart-breaking response to our google form:

“I think all of these issues with body image and the lack of plus size people in Oxford is heightened in the queer scene – it feels like there’s a cookie cutter image of what “queer” looks like at this uni and that’s often very skinny and white. The only place that I’ve actually been verbally assaulted about my weight in Oxford is in the gay club Plush, on several occasions by queer men/nbs who have shouted things like “fat bitch” and worse at me while I’m just dancing with my friends or trying to get out there in the queer scene and meet someone.”

“As a queer woman, I feel particularly insecure when getting with other queer women/I feel myself comparing myself more which is stupid”

This need to be more “feminine” might not be as present amongst the queer community here, but it still presents itself when queer students “seem to care about the male gaze much more than the female gaze”. One student also said that, regardless of how feminine they were, they were worried that they weren’t “‘gay enough’ for women.” Pretty privilege also presents itself in the queer scene through the way that it affects trans and non-binary students:

“It’s difficult navigating dating – wanting to be seen as attractive and seen as my gender can feel at odds with each other. I worry I am only considered attractive when I’m not being seen as my gender.”

“Trans women especially I’ve seen be more likely to be misgendered and mistreated if they aren’t deemed attractive or feminine enough to “pass”.

Whilst the queer scene can serve as some sort of an escape from cis and heteronormative standards of beauty, there are still people within this community that hold these values.

I also received an overwhelming percentage of written responses from people of colour. Before I show them to you, I want to give you a quote from Candice Carty-Williams’ Queenie came to me when I read these responses: “You know, when we go out, my friends get chatted up by guys who say, ‘I’d love to take you for dinner, and in the same breath they come over to me, put their hands on my bum and tell me they want to take me back to theirs and fuck me”. I think it perfectly encompasses the disparity that is felt between the treatment of people of colour and white people, especially in the dating scene. The only thing that I would add is the way that there were other people of colour who these same guys would overlook. These were a couple of other responses that I received:

“I’ve never dated so I wouldn’t know, but I’ve low-key accepted that I might be single for the duration of my degree, because I think it’s harder to date as a POC here. Not only do I worry about not meeting the beauty standard, I do want to meet someone who’ll like me for me, and not fetishise me.”

“Look around and ask why so many beautiful beautiful WOC are passed over in Oxford compared to fairly average-looking blonde upper-class counterparts – there are exceptions but it’s so weird to see attractive people at uni regularly discussed without anyone mentioning this.”

I’m sure at this point you’ll have noticed that I’ve focussed a lot on the dating scene at Oxford. This is, in part, because many of those who responded to my survey would bring up how they’ve been impacted by pretty privilege in Oxford without prompting. It is also because I think that the impacts of pretty privilege are exacerbated and demonstrated more strongly in the prominence of the dating scene in Oxford. It is a brilliant demonstration of how those who benefit from pretty privilege receive more attention or free drinks based on the way that they look.

When asked about how others have experienced pretty privilege, this was a common response that I received:

“A lot of people who have pretty privilege don’t particularly like to admit it, I’ve found they like what they get from it. It’s not a bad thing and it makes a lot of sense, no one would pass up the opportunity realistically”

This is a really difficult problem to be faced with because when someone benefits from pretty privilege, they may not realise it because being given a free drink or a discount by someone who likes the way you look could easily be interpreted as that person “just being nice”. They may not even see themselves as pretty and won’t see it as pretty privilege in the first place. But someone else may step up behind them, not as conventionally attractive, and get a nod before they’re charged the full price for the same thing. It’s a sure way to strike down someone’s confidence especially when no-one around you can see what all of these people have done wrong. A lot of the time, it comes across as confidence or sociability:

“Friends who are absolutely beautiful with regard to conventional beauty standards tend to make friends more easily I think – they never EVER acknowledge that their appearance has anything to do with this though”

It can take time to realise this. When you first find these friends, it seems as though they’re just confident. It’s inspiring! They serve as role models to boost your own confidence and need to be outgoing. Suddenly, one day, the penny drops. The likelihood is that their confidence comes hand in hand with the fact that they’ve not had to scrutinise every physical aspect of themselves to get what they want. For example, one interviewee described how she internalised people’s opinion that her afro-textured hair would be “taking up too much space”. As a result of this, she became aware of how her personality took up too much space. The same has been said by interviewees that felt self-conscious about their weight:

“Being overweight naturally means you take up more space so I have a fear of taking up even more space ‘than necessary’.”

It’s a frustrating never-ending cycle of both external and internal bias surrounding your appearance which means that whether or not we fit into the frame of “pretty” also has a huge impact on our confidence. Even if they share their free meal with you, it may not necessarily soften this blow at all.

However, I don’t want to ignore the fact that pretty privilege is not costly to those who might benefit from it. For example, one person brought up how, whilst she has benefited from economic pretty privilege (in receiving gifts etc.), she has felt that she has suffered from “the beauty penalty as a woman in an academic setting” because “if there’s a woman who got somewhere high up, yeah, they either slept their way to the top, flirted their way to the top, or somebody liked the look of them and wanted them to hang around”. Some people also discussed how being pretty opened you up to sexual violence:

“If you’re a woman then [pretty privilege] is sort of balanced out by the fact that you’re going to get catcalled and objectified and have a sexual harassment and sexual violence like that.”

Prettiness can also be distorted for non-binary and trans students:

“For afab non-binary people – people such as myself, it can be the other way around and “prettiness” becomes less of a privilege, as it is often be tied to being misgendered as a woman.”

This has been a difficult article to write because, honestly, it seems like there’s no winning, and the only truth that I’ve found in this is that these qualities, these conventions of pretty privilege benefit one person and one person only and that is the (usually straight) tall, athletic, rich, white, blonde man that we all see as the Oxford poster boy.

Well, what’s our solution to all of this? One of my interviewees highlighted that this is not something that can be measurable in the same way that a company could measure how many employees are women/people of colour/non-binary people. However, just because this is not a measurable bias, this should not be your response:

“It isn’t gonna stop, so grit your teeth and bare it”

Please don’t let this stick with you, despite the “doom and gloom” feeling of this article so far. Yes, we’ve seen that pretty privilege exists and that Oxford is not immune to it. I don’t want to let the pedestaled image of the Oxford poster boy damage your confidence any more than it has already. We didn’t let that guy stop us from getting here, we didn’t let him stop us from studying the subject that we love, hating the texts we have to read (thanks Milton), or the tute sheet that’s staring at you from your desk. Please! What authority does he have to make you look in the mirror and hate yourself? Or stop you from having a boogie at the musicals night at the Bullingdon, auditioning for your favourite play, or asking out that person you’ve been ogling at in the RadCam? The best takeaway that I’ve had from these surveys and interviews is that people have felt more able to express their individuality in Oxford. Yes, this place was made for that poster boy, the man who can give you a charming smile or will promise his entire trust fund to the “thin sexy hooker virgin with boobs and hips but not big ones”(see Leading Lady Parts, BBC on Youtube). But look around you. We’re not all Keira Knightley or Jonathan Bailey but nor should we be. If this sermon didn’t do it for you from yet another student journalist, then try my favourite pieces of advice that some of our interviewees would give their Fresher/Term1 self:

“Oxford is a bubble and other people’s perceptions of you don’t matter! Everyone is beautiful”

“Don’t stress about your appearance, there’s not much you can do about it. Just be grateful for what you have, think of all the things you like about your appearance and focus on being your best self. A beautiful personality goes a long way :))”

Stick that on a Fresher’s T-Shirt.

Support information:

For student counselling services please email: [email protected].

Nightline: 01865 270 270

Sexual harrassment support service: supportservice@danselinger

Image credit: W.S. Luk