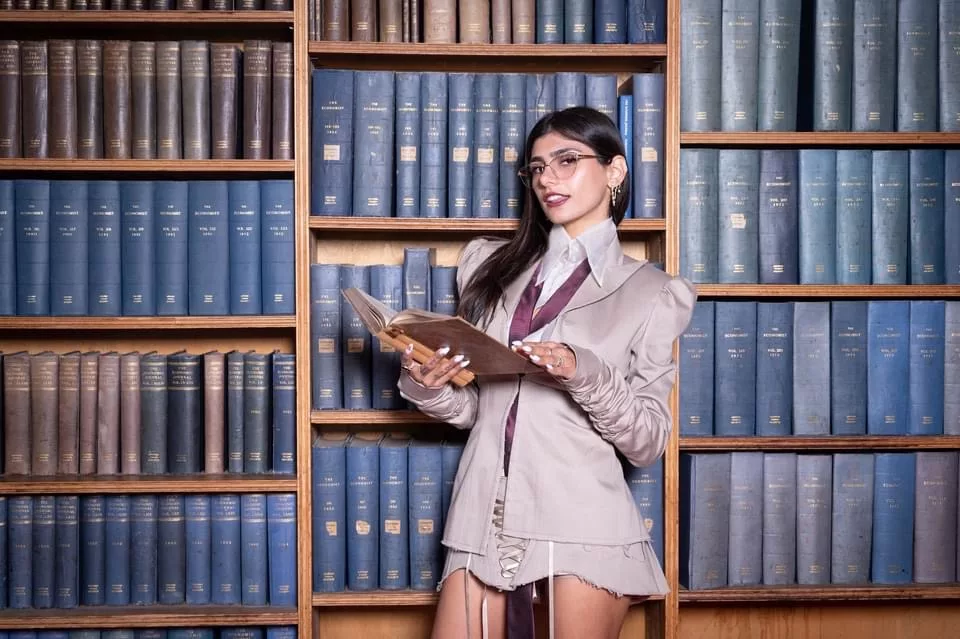

At 17:35 on May 3rd, I received an email from the Oxford Union Press that in about 2 hours I would be interviewing Mia Khalifa before her speech at the Union that evening. I paused mid-essay, suddenly struck by the fact that I had no questions prepared and was about to meet one of the most infamous, and most stylish as we all saw at her speech, women in the world. As I scrambled for questions, I realised that the image of Mia, the questions that people may expect me to ask is related to a past that doesn’t really represent Mia for who she really is. Woman to woman, I wanted to know Mia Khalifa, whose real name is Sarah Joe, for who she is now, as a person, a human being, a woman, and a person of colour.

Entering the room at 19:55 pm I greet Mia who is all smiles. She’s shorter than I thought she would be but much kinder. I tell her she looks amazing and she compliments my eyeshadow. While we bond over our love of Fenty I realise Mia truly is a girl’s girl. She’s the kind of girl that gets on better with other girls, a quality that I think is the greenest flag to spot in any girl.

We finally manage to settle down and I ask her what it was like growing up as a Lebanese girl, and how that influenced or affected her relationship with feminism. She told me “It’s really difficult to grow up Catholic and Middle Eastern because I feel like there’s a lot of just inherent misogyny, inherent roles that get assigned to, like, daughters get treated so much differently than sons, which I feel like can be related to in so many other cultures, not just Lebanese culture. It’s very much that in the Middle East. The man is the provider. The woman is the supporter, that kind of mindset. So my outlook on feminism growing up was what I was taught around me, which is why I feel like I had so much internalised misogyny. It took me a while to grow out of that, but I don’t think it positively skewed my view on feminism.” We bond over our experiences as women of colour. “I’m Nigerian,” I tell her, and we agree on how our cultures influence our views on how we should act as women and how we are perceived.

But our cultures also look down heavily on sex work and the adult entertainment industry, despite the hypocrisy in that men still see us women as sexual objects. I ask Mia how she relates or reacts, given her experience in the industry, to the increasing number of women getting involved in sex work, whether stripping or OnlyFans, and citing feminism and empowerment as their reason for it. Her answer is firm, speaking from her own experience in the industry, she answers, “I do not think it’s an act of empowerment, I think it’s actually very dangerous to push that rhetoric. I think that it should never be a first option or something that’s packaged as empowering or freeing or anything like that. I think that’s very dangerous, and it’s borderline grooming. I think there are empowering ways to do it once you’re in if there are no other options for you, but I would never promote it as something simply empowering. Don’t do it if you’re looking to do something empowering.”

In November of Michaelmas Term 2022, the Union was visited by another personality who opened an OnlyFans account in 2021 just a few days after her 18th birthday, and allegedly earned over $1 million in revenue in the first six hours, and an alleged total of over $50 million. Facts like this put into perspective what Mia is saying in regard to grooming. In her talk in the Union, she elaborated on this, stating that the narrative that OnlyFans and being a sugar baby and other forms of sex work are being pushed to you young women as safe and easy ways to make money and express themselves, yet this is not the case. Mia maintained that it was “absolutely grooming”, and expressed a wish that young women would not turn to sex work unless they really had to for fear that that digital footprint would follow them for most of their lives.

Speaking of a digital footprint, it was time to ask Mia about what she was most well-known for. In all honesty, I did not want to ask this question. Despite being curious myself, I knew too well what she had gone through at that time, and to ask her to relive that experience felt wrong. Yet, I ask, “You’ve been criticised by men for daring to have a sexuality and by women for supposedly misrepresenting them, for example, the hijab video. As a woman and as a person of colour as well, how do you react to the backlash from your history in the adult entertainment industry?”. Mia says “I don’t really get let it get to me too much. I know that I’m not the one who invented the fetishization of the hijab or of the Muslim culture or anything like that. In fact, it was straight white men who wrote the scene.” What Mia is referring to is Orientalism, a term established by 20th-century Palestinian philosopher Edward Said. The term criticises the West’s derisive depiction of The East. The over-sexualisation of Arab women found in movies, one of the most notable examples being Princess Jasmine from the Disney movie Aladdin, is a massive problem within the West. Men are obsessed with the idea of unveiling Muslim women, hence the market for it, not only in porn, but also in TV shows and movies which feature a female Muslim character removing her hijab for minute reasons, oftentimes irrelevant to the plotline. The over-sexualisation of Arab women doesn’t stop there, Native American, East Asian, Black, South Asian, Romani and Latin American women are all victims of the over-sexualisation of their bodies and their culture. It is unsurprising that these groups of minority ethnic women experience rape and sexual assault at significantly higher rates than white women, with the National Center on Violence Against Women in the Black Community stating that one in four Black girls will be sexually abused before the age of 18. The fetishization of ethnic minority women is commonplace, and a dangerous phenomenon that puts women in danger, but Mia says it is important to remember that these stereotypes were invented by “straight white men in suits”. It was these men who were the ones who pressured her into that hijab scene when she was 21, despite her protests that it was wrong, as she revealed in her Union speech.

Knowing this, it’s unsurprising that Mia veered away from the sports world. “I was heavily involved. I had a sports show a couple of years ago it was complex. And I was very heavily involved in the sports world up until about two years ago when I actively made a decision to kind of stop taking jobs that were centred around that, just because I feel like the fan base isn’t one that I wanted to cultivate. It was young men, and it wasn’t serving me. It’s just not a fan base I want. So I realised the more sports I’m involved with the more I’m going to be exposing myself to that demographic. So I made a conscious decision not to do it anymore. It was a very difficult decision, like very difficult.”

So if she’s no longer doing sports commentary, what’s in store for Mia Khalifa? What does the future hold for the influencer and activist? According to Mia: “So much!” Her enthusiasm about her future is infectious as she tells me, “I’m launching a jewellery line. I’m doing a lot of things that I never dreamed I’d be doing, like speaking. Honestly. There’s a lot on the horizon that I’m very much looking forward to the end. It aligns with me and who I am. And I’m also happy with the audience that motivates.”

As Mia seeks to cultivate an audience of women who are inspired by her and move away from the young impressionable boys who seek her content for laughs, she re-establishes herself and takes back control of her name, her social media, and her actions. Though she jokes that “Being delusion is the best form of therapy” she advocates for going to therapy and mending your mental health, which is just as important as your physical health.

Her talk at the Union resonated with many audience members, from women to fellow Middle Easterners, enjoying both Matthew’s questions and Mia’s answers. Consequently, we look forward to Mia’s future and all that she hopes to achieve as her talk at the Union signifies her first step to building a better audience.