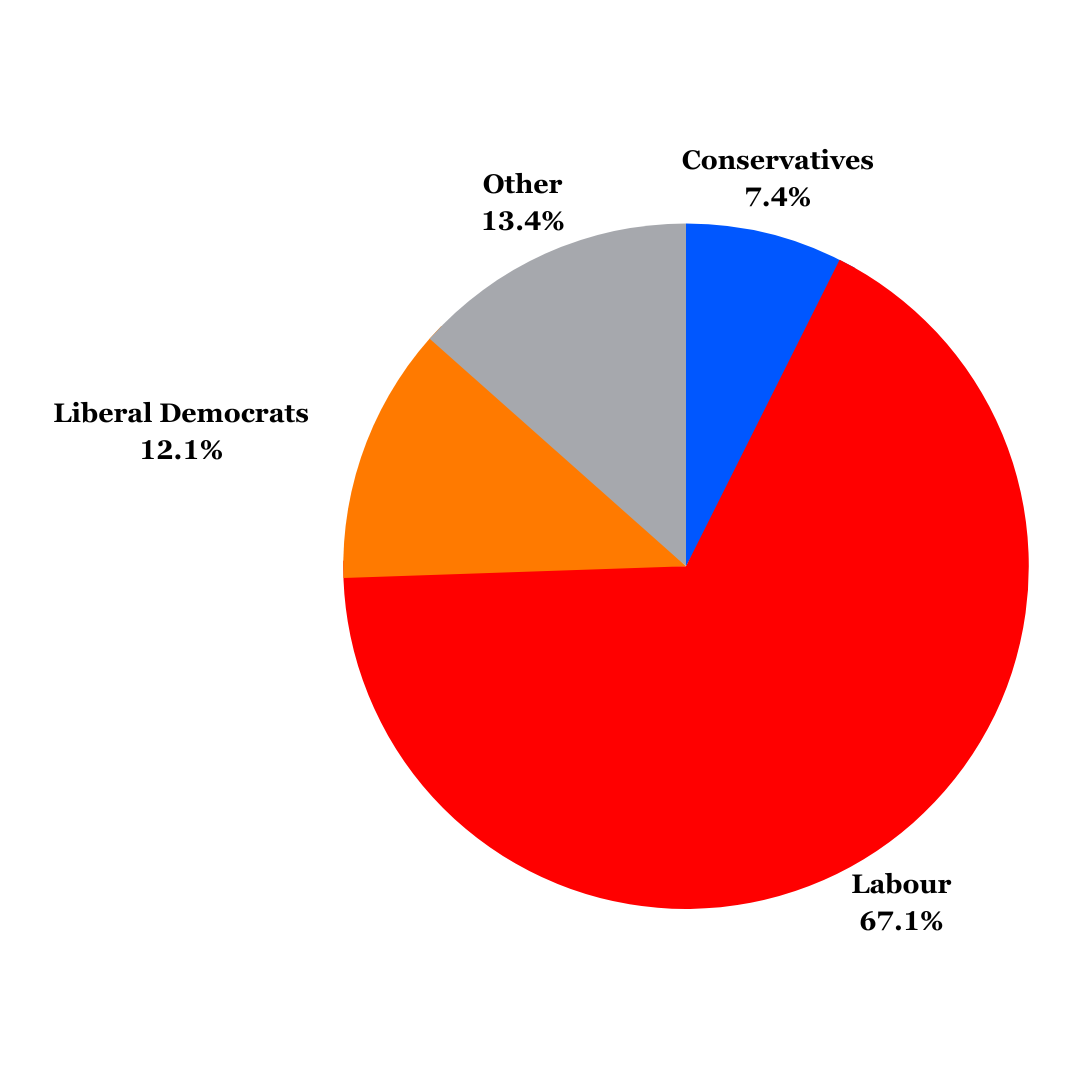

A recent ‘View from Oxford’ survey polled students about which way they would vote in a general election. The results showed that 67.1% would vote Labour, 12.1% Liberal Democrat, 13.4% Other, and 7.4% Conservative. This poll raises important questions regarding Oxford’s students’ political make-up. Are we in our own bubble here? Or is something else at play?

Firstly, there is the argument as to whether Oxford reflects nationwide political feeling, or whether it’s contained in its own political sphere. Compare the above-given statistics to those from a national poll on the 20th of October undertaken by Politico. In this instance, Labour leads at 45%, with the Conservatives behind at 27%, Other at 15%, and the LibDems at 11%.

What the view from Oxford’s poll makes clear is that Oxford leans far more heavily towards the Left. But even further than that, there must be more to this trend than the general tide of anti-Tory feeling which has been swelling up everywhere since at least the start of Partygate. The divergence that exists between Oxford University and the country at large may simply be down to the general rule that young people are left-wing. Though, of course, the data is completely at odds with the rest of the country’s perception that in Oxford ‘they’re all Tories’. This then raises a further question: What about divergences in public opinion within Oxford itself? The bubble within a bubble debate.

Everyone knows the College stereotypes. Oriel is so keen on Rishi that it really ought to be named Toriel; though a close second for that title is Corpus Christi, with its unironic campaigns for a ‘Conservative rep’ on the Equal Opportunities Committee in the past. If we look the other way, Wadham’s ultra-left-wing reputation is also renowned as they seek to nationalise, among other heavy industries, our kebab vans.

Though, as widespread as these stereotypes are, I’m not convinced. To explain why, I’ll outline my own experiences with college stereotypes. I am at Christ Church. When I tell anybody in Oxford that I go there, they tend to give me a look of disgust. This is probably because they’ve made the usual false assumptions about how, with its disproportionate intake of private school pupils, it is a hotbed for Toryism. Or perhaps it’s that once you get there, you can barely move an inch without treading on some clone of Jacob Rees-Mogg. But as a creature of Christ Church myself – and one who has ‘talked politics’ to a number of fellow creatures – I’ve quickly realised that nearly everyone who keeps up with politics is a Labour supporter. I have yet to meet any fans of Reform UK, the National Front, or the Official Monster Raving Loony Party. Of the three Conservatives I have met, one pleaded that he was hoping for a Labour win at the election, another refused to elaborate, and the third began singing the national anthem.

In other words, the whole stereotype is nonsense.

If you disagree with my experience, the next best step is probably to approach the problem logically. Think of the improbability that each college, with a fresh slate of applicants every year, perfectly replicates its political make-up. Is it really convincing to suggest that they would go to the lengths of , selecting just the right number of pupils from the required persuasion, and discarding the rest, who would be taken up in equally perfect proportions by the other colleges? It’s absurd; what’s more, everyone probably knows it’s absurd.

Now, having established that it’s nonsense I wonder why these stereotypes persist year after year? And where did they originate?

Well, the stereotypes persist year after year because they are as much a part of the Oxford tradition as boat-racing or matriculation. It may be wrong to judge someone by their background, but in Oxford, it would be even more wrong not to do so.

As for their origin, it probably varies on a college-to-college basis. If I wanted to use a get-out-of-answering-free card, I would say that these bubbles within bubbles are down to wheels within wheels: it’s complicated and affected by disguised or indirect influences.

By this reasoning, Somerville’s reputation for diehard Toryism is probably down to the fact that Thatcher went there. Likewise, St John’s notoriety for launching illegal wars in Iraq may have something to do with Tony Blair having attended in the 70s. But because the issue is much more complex than this, these colleges obviously did not gain this reputation. The absurdity demonstrated in these two instances might as well reflect the stupidity of the others.

Harmless nonsense, though, and nonsense that I personally would back to last as long as the myth of the greatest of all folk devils: ‘the Other Place’.