‘I found I had a soul congenial to his’, John Dryden wrote in 1700. ‘He’ is Geoffrey Chaucer. There is a three-hundred year gap between the former, a Restoration-era satirical wit, and the latter, a medieval poet. Despite Dryden’s critique that Chaucer often ‘runs riot’, lacking a filter altogether, mingling ‘trivial Things with those of greater Moment’, something remains between their two souls. Dryden judges himself close enough in essence to Chaucer to deserve his role as translator. After a few terms studying Chaucer firmly within his own era, I was interested to see how much truth there was in this statement, whether our own souls could indeed be made more congenial.

The question of what ‘remains’ is the focus of ‘Chaucer Here and Now’: an exhibition at Oxford’s Weston Library, running from December to April. It is wonderfully curated by Marion Turner, the current J.R.R. Tolkein Professor of English Literature and Language. The exhibition itself is absorbing; as you move through it, an argument unfolds. It is tightly structured, tied together by the concept of ‘reinvention’, as Turner shows how every century from the fourteenth to the twenty-first has moulded Chaucer to their own tastes. We begin with the earliest manuscripts, featuring mansplaining scribes, scandalised censors, and unfinished endings. Even from day one, there is no stable and single Chaucer: manuscripts are notoriously collaborative. Chaucer was not too bothered about his endings, leaving works like The Cook’s Tale hanging after only fifty eight lines; scribes often finished this for themselves. The exhibition then dedicates a whole section to The Wife of Bath’s Prologue, which Dryden famously refused to translate; he declared ‘tis too licentious’ for all its talk of ‘bigamye’ and ‘octogamye’, as well as its ironic stabs at Biblical hypocrisy. King Solomon was hardly the paragon of monogamy.

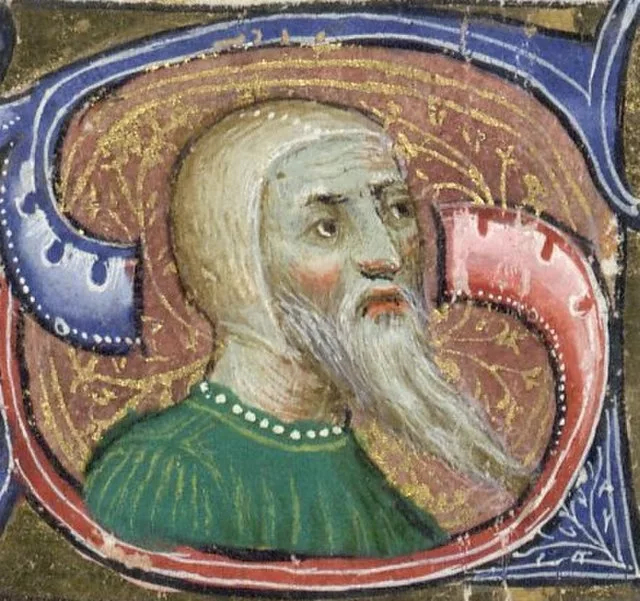

But it is really the beauty of the books that makes the exhibition come alive. Gathered partly from the Bodleian’s archives, all the famous Chaucers are on show. William Caxton’s 1483 edition, complete with early woodcuts is unmistakable, helping to bring Chaucer’s pilgrims to life. The 1896 Kelmscott Chaucer, though, a huge Pre-Raphaelite edition covered in white pigskin, is most spectacular; its creators called it a ‘pocket cathedral’ for its magnificent illustrations – seriously, Google it! The interwoven vines, scattered autumnal leaves, and monochrome illuminated lettering play into the Victorian re-imagining of the medieval era, full of rural idylls and tragic Arthurian love. It is an attractive idea, making for an attractively illustrated text. But it is also entirely inaccurate, skewing the reader’s understanding of Chaucer.

Turner is keen to avoid a ‘Merry England’ view of Chaucer in the exhibition. As in her recent biography, Chaucer: A European Life, she emphasises the deeply cosmopolitan side to Chaucer; he was multilingual, travelling to Spain and Italy, in contact with then-modern Italian writers like Petrarch and Boccaccio, and importing new and innovative forms like the rime royale stanza into his poetry. It is this (then)-edgy experimentalism which we value most today. He blends and juxtaposes registers, characters, and influences; his diverse group of pilgrims meet in a pub in Southwark, telling a range of tales from the high-status knight to the bawdy miller. The exhibition has screens and headphones to watch an early-2000s BBC adaptation of a few of Chaucer’s tales, which convey this eclectic mix well, as the animators use a different style for each tale.

Medieval studies are currently under fire, steadily losing popularity in a time when ‘relevance’ is looked for above all else. I found ‘Chaucer Here and Now’ to do a brilliant job of communicating the intrinsic interest of Chaucer’s works – much more humorous, witty, and experimental than we give him credit for – whilst also seeing them as a lens through which to explore the culture in which they are received. Inevitably, each reader will set him against themself, recognising the sparks of immediacy which chime with their own experience. The exhibition’s final section, focusing on postcolonial re-imaginings, shows just this. Turner offers us a wide selection of books – also available to read in the Weston’s sofa area – such as the Refugee Tales, which expands upon Chaucer’s idea of movement and displacement, as well as Zadie Smith’s play The Wife of Willesden, and Jean ‘Binta’ Breeze’s ‘The Wife of Bath in Brixton Market’. Do go and see this exhibition; it will shake up your understanding of the medieval period, just as it helped me to reinvent an author who can be far too easily pidgeonholed into his exam-essay context. Or, if nothing else, there’s birdsong playing as you walk in.