Few modern comic heroes align with our distinctive age – an age which Dickens’s famous opening, ‘It was the best of times, it was the worst of times’, would easily resonate, and an age in which progress and innovation coexist with existential threats. Jeff Kinney’s literary forebears, those of the disillusioned and hubristic comic hero tradition, lie firmly in the twentieth century: the gloriously self-important Mr Poots, Orwell’s ostracised bookseller Gordon Comstock, the ever-exasperated academic Jim Dixon, and the acne-riddled Middle-England poet Adrian Mole.

Greg represents all of the hubris and ‘self-irony’ of this literary tradition, and this is where the series’ comic appeal lies. For instance, his constant belittlement of his best friend Rowley Jefferson, and pretensions of grandeur by comparison, is confounded when Greg’s paranoia leads their mutual date, Abigail, into Rowley’s arms in The Third Wheel. Yet in his distinctive ‘David Brent’ mould Greg’s heroism is consistently balanced with some pretty unsavoury characteristics. Between his disregard for Rowley when he breaks his arm in the original book and his failure to take responsibility for wrecking his Dad’s car in Old School, we do not find a particularly noble or virtuous character in Jeff Kinney’s volumes.

But is that what we want when we turn to comedy? Probably not. Rather, it is the passages of ironic brilliance, that elude self-realisation, that resonate with us and make us laugh. Just as Sue Townsend’s Adrian Mole fails to recognise the shortcomings of his ultra pretentious avant-garde literary style, Greg’s comic strip is superseded by Rowley’s genuinely funny Zoo Wee Mama! comic in the school newspaper. In a quest for popularity that does not dissipate throughout the series, Greg also demonstrates his shallowness. After becoming the most popular kid in school for being able to tell the time at his terrible new school in No Brainer, his newly bestowed title of “Time Lord” beautifully characterises his self-delusion – or maybe reflects a sense of pragmatism that, if he becomes popular based on being able to tell the time, so be it.

The twenty-first century could well be perfect for the sense of disillusionment which pervades every volume and affects Greg’s actions so decisively. And through its engagement with deeply contemporary issues, the series explores being a teenager in an age which should have everything, yet in which there are new and troubling challenges. His battle with his anti-technology mother at the beginning of Old School pits the generations firmly against one another – an Arkady bringing the modernising Bazarov to the sceptical older generation.

But it is the trip to a tropical resort in The Getaway that most embodies our ambiguous and sometimes pessimistic age: his high expectations of paradise are confounded by what has become the epitome of modern tacky commercialism. If his parents are Adam and Eve going back to their prelapsarian nirvana, then Greg is the voice of their fallen descendants, wrestling with the snake of disappointment. He must reckon with the frustrations of modern life, just as Orwell’s neurotic Gordon rails against the modern “Money God” that conspires against his relationships and writings.

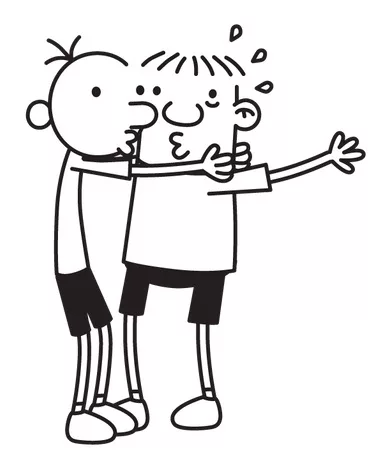

Yet, between the dating failures and the strains of family life, there remains in Greg a profoundly human capacity for kindness and humility. This provides a heartfelt, necessary counterpoint, and reminds the modern reader of the possibility and everyday reality of goodness in our times. His reconciliation with the recently broken-up Rowley in Hard Luck allows Greg to bury the hatchet with his oldest friend; when the proposed Heffley house move in Wrecking Ball threatens to break the friendship apart again, and does not materialise at the eleventh hour, the final scene of them reunited reminds the reader of the tenderness of relationships forged over many years.

Here Greg experiences a rare and cathartic moment of self-realisation: his friendship with Rowley is more important than any new house. The dichotomy between constant self-delusion, and self-realisation in the critical moments, provides the reader both with searing humour at Greg’s expense, and yet the final recognition that he can overcome his flawed personality and relationships to preserve what matters – so the bumbling David Brent reconciles with his Wernham Hogg colleagues in The Office’s dying moments. The 3-pointer Greg accidentally makes at the end of Big Shot, having been traded off his basketball team by his own mother, emphasises this unlikely heroism. Happiness in an uncertain world may come from unexpected places. It is his unimpressive ability to tell the time, rather than any self-deluded attempts at romance, that finally gets him a girlfriend in No Brainer (if only for a few pages). And if the perennially under-achieving Greg can find success, so can we all.