The Griffin Catalyst Exhibition, The Charcoal Heads, shows the early career of Frank Auerbach and the creation of his portraits in the 1950s and 1960s. As a young Jewish artist alone in post-war London, the charcoal portraits reveal a lot about the artist’s own personal experiences and the valuable relationships he established with the sitters of his portraits. As such, when observing the visitors of the exhibition at the Courtauld Gallery, it became clear that they, too, were attempting to uncover the metaphorical layers of discovery and experience present in his portraits.

It was almost as if a conveyor belt had been installed within the gallery as each drawing was observed by a different visitor one after the other. The visitors matched the pace of their neighbours, taking their time to examine the charcoal heads on display. Whether meeting the sitter of the drawing at eye level or bending forward to see the portraits in more detail, visitors were face to face with the solemn individuals drawn by Auerbach. As such, whilst the sitters of the portraits appeared close to death in their sunken cheeks and solemn eyes, they remained omnipresent within the art gallery, holding their presence as visitors circled the room.

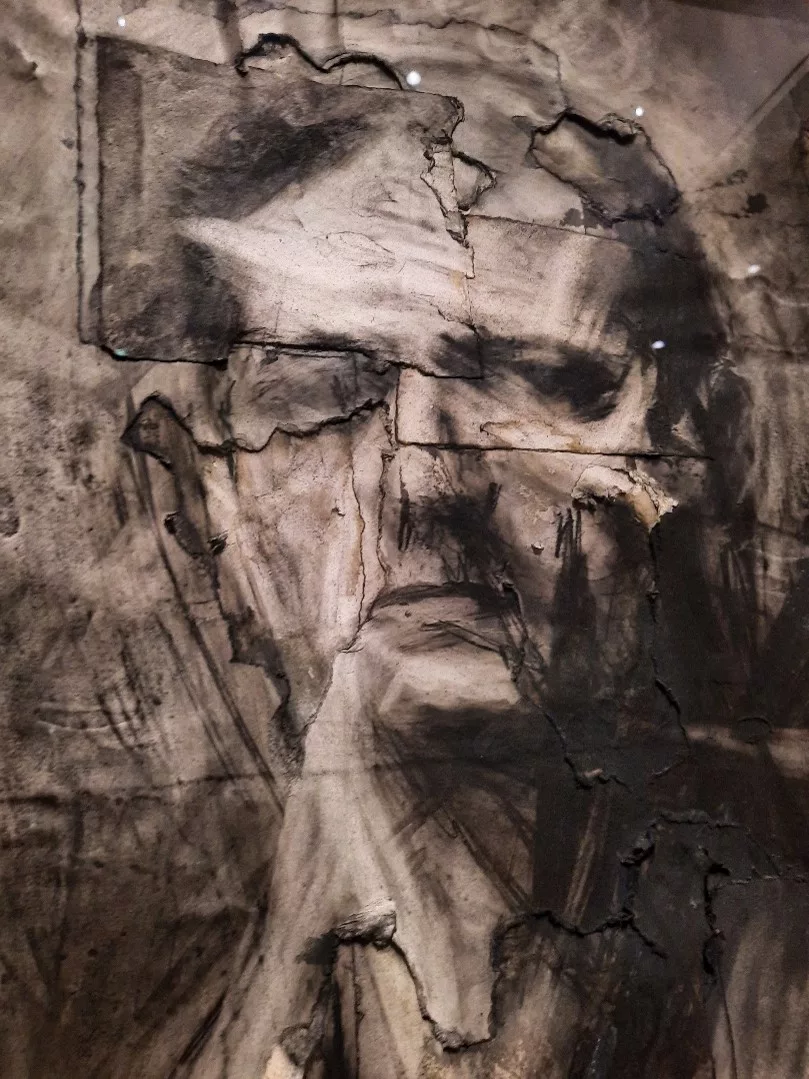

However, one drawing, in particular, broke this cycle as a crowd of visitors surrounded Auerbach’s 1958 self-portrait at the age of 27. It was common for Auerbach to rework his drawings, yet the self-portrait on display appeared to have undergone excessive alterations. Its textured and layered appearance resulted from it being patched up three times, which led to the image of the young man becoming warped and disfigured. The scars created from his own human experiences were translated through the white folds which radiated in contrast with the dark charcoal shadows of the piece. It was in this moment that I understood Robert Hughes’ statement in the 1990s that “an overriding sense of being alone in the world” was at the centre of Auerbach’s work.[1] The artist was just as much a stranger to himself than his sitters and it was only through numerous sessions and changes that he could come to terms with his own experiences through the artwork he created.

Auerbach’s self-portrait of a stranger reveals that, rather than Auerbach imposing order through his artistic processes, the creation of his portraits was an attempt to make sense of his own position during a period of chaos and displacement. Auerbach continually revisited his artwork, where his finished portraits are highly textured and reflect on the deepest experiences he faced. Therefore, whilst his work was highly considered, Auerbach continually reviewed his work as part of a process of self-discovery. This is illustrated by the unexpected strikes of pink and blue that appear throughout his portraits, suggesting a sense of emotional and artistic spontaneity.

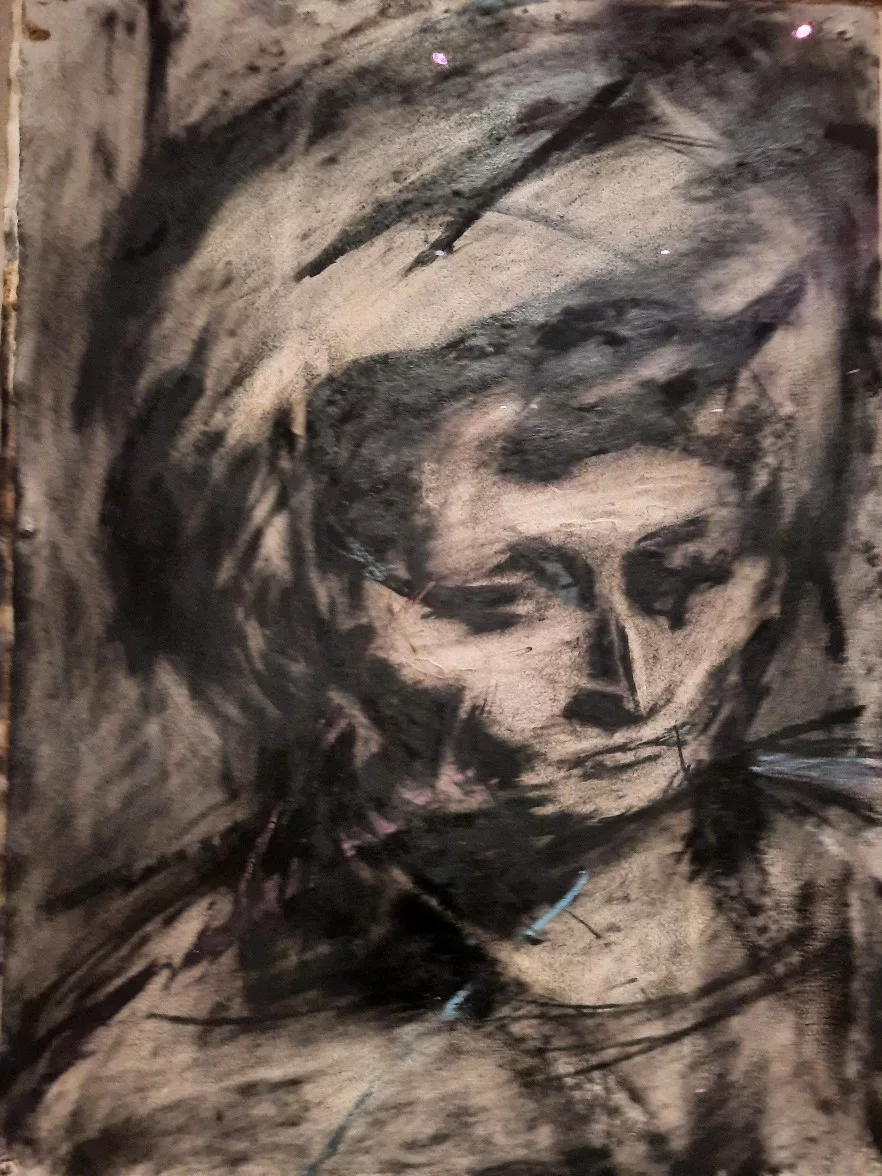

The power of Auerbach’s artistic process is further evident in three drawings of Gerda Boehm. Gerda and her husband had fled Nazi Germany in 1939 and settled in London. Earlier that year, Auerbach was also sent to England under the Kindertransport scheme whilst his parents died in the Auschwitz concentration camp in 1942. Hence, initially, the Boehm family were the only relatives that Auerbach had in England. Gerda, now a widow, first sat for Auerbach in 1961 and would attend sessions weekly until the 1980s.[2] Auerbach’s initial drawing of Gerda is displayed at the Courtauld. Despite the numerous sessions Gerda had with Auerbach, there are no signs of rips or tears as seen in his self-portrait. The portrait embodies a sense of familiarity and maternity that the artist likely felt towards his sitter. The drawing, therefore, reveals a sense of harmony between them, which was a consequence of their shared experiences of hardship.

Whilst there is an overwhelming sense of darkness to Auerbach’s portraits, the artistic and real-life challenges faced by the artist are symbolically overcome by the final creation of his drawings. At a time of post-war reconstruction and reflection, Auerbach appears to reimagine the identity of his sitters, providing them, and himself, with a new and vital presence. Just like the streaks of blue and pink that remain vivid against the dark smudges of charcoal in his drawings, the individual figures emerge as alive, despite the struggles they faced.

[1] Dale Berning Sawa, “’I’m doing what may be my last paintings’: Frank Auerbach on his new self-portraits and turning 92″, The Guardian. April 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2023/apr/25/frank-auerbach-artist-self-portraits-last-paintings.

[2] Tessa Lord, “Reclining Head of Gerda Boehm”, Christie’s. 2021. https://www.christies.com/en/lot/lot-6309474.