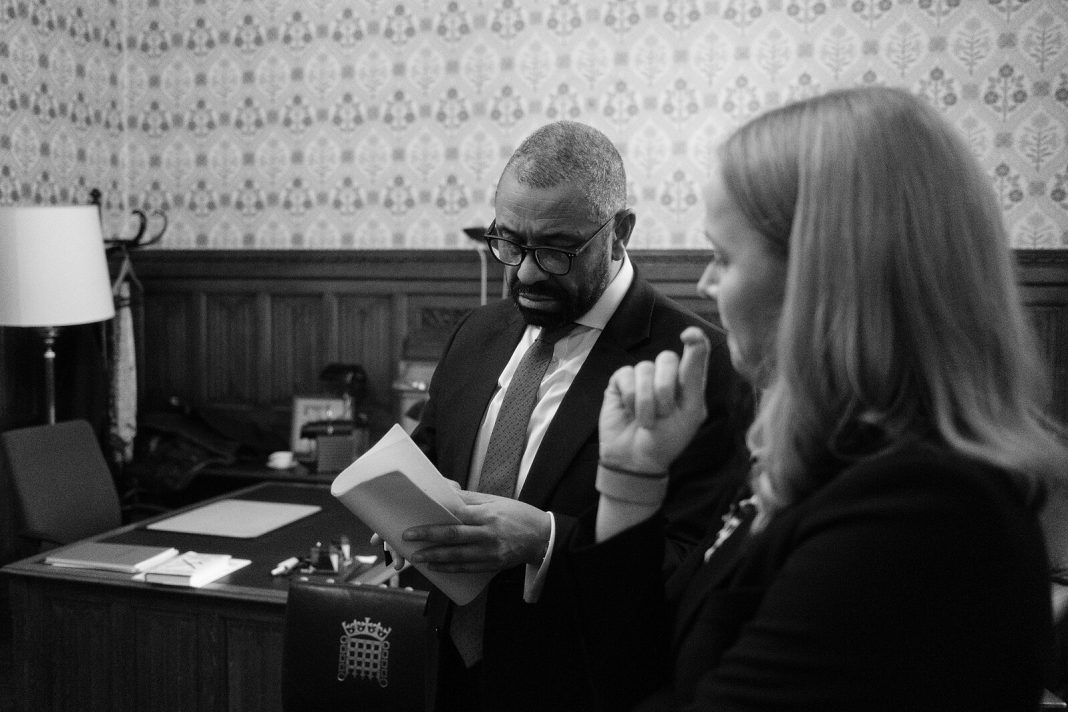

“Batshit crazy”, was how one cabinet minister (James Cleverly) described the Rwanda policy. In his former role as chancellor, Prime Minister Rishi Sunak was characteristically more reserved, saying “it won’t work”. Human rights organisations are less kind: “This would be a clear breach of the refugee convention and would undermine a longstanding, humanitarian tradition of which the British people are rightly proud.”, said the UNCHR when the policy was announced. When announced in 2022 by then-Prime Minister Boris Johnson it was branded by most (including initially Johnson himself) as a laughable concept that would never be implemented and yet here we are two years later. All norms of parliamentary and legal process have been tossed out, the right wing of the Conservative Party continues to call for Britain to withdraw from the European Court on Human Rights (ECHR), and the Sunak will have you believe that “No ifs, no buts, these planes are going to Rwanda”. So how did we get here, what planes might actually go to Rwanda, and will they have anybody on them?

The only place to start is more than two years ago on 14 April 2022 when Boris Johnson announced his plans to deport those arriving in the UK on small boats to Rwanda for their claims to be processed. Independent human rights organisations disagreed but Johnson insisted that the country was in fact “one of the safest countries in the world”. How that would also provide “the very considerable deterrent” that he claimed it would was a mystery at the time and continues to be today. Importantly, the plan that Johnson outlined at the time would allegedly have seen “the capacity to resettle tens of thousands of people in the years ahead”. Fast forward to June that year and the first flight bound for Rwanda was grounded minutes before takeoff after an injunction issued by the ECHR. That plane only had seven people on board.

After that, the plan somewhat vanished from public consciousness until Suella Braverman rekindled it at the Tory party conference in October, telling a crowd that “a front page of the Telegraph with a plane taking off to Rwanda, that’s my dream, it’s my obsession”. (It is also worth pointing out that Braverman is against the current plans, which she doesn’t see as extreme enough).

In March 2023, Home Secretary Braverman introduced ‘the illegal migration bill’, which became law in July. It was there that the home secretary was given ‘a duty in law’ to detain and remove those arriving in the UK illegally, either to Rwanda or another ‘safe’ third country. Notably, detainees were not entitled to any appeal, bail, or judicial review for the first 28 days of their detention.

In November of that year, the Supreme Court ruled the policy unlawful, upholding a court of appeal ruling that there hadn’t been any proper assessment of whether or not Rwanda was safe, with ‘substantial grounds to believe that deported refugees are at a risk of having their claims wrongly assessed, or of being returned to their country of origin to face prosecution’. That might surprise the more trusting of you, who believed the government line that sthe policy had been “designed with empathy at its heart”. It did not surprise Sunak. Rather, he already had civil servants working on a new treaty to get around the ruling and that ‘he was willing to change the law’.

And so to December, and perhaps the most barely believable moments of the saga to date. James Cleverly became the third home secretary to travel to Kigali and announced a new treaty that he said ensured migrants would not be returned to a country where their lives would be threatened. The next day, the government introduced the ‘Safety of Rwanda (asylum and immigration bill)’, perhaps the most extraordinary example of government overreach into our judiciary in memory. Former Supreme Court Judge Lord Sumption, said at the time that “it would be constitutionally a completely extraordinary thing to do, to effectively overrule a decision on the facts, on the evidence, by the highest court in the land.” This bill rules that Rwanda is a safe country and must be viewed by politicians, judges, and anyone else as such. There is no time limit on this judgement, there is no scope for its review. Despite the attempts of various crossbench and Conservative peers in the House of Lords last month to add amendments, the government refused to compromise on any. That was when, once again, Sunak stood behind his podium in Downing Street emblazoned with ‘Stop the Boats’ and said that Parliament would sit for “as long as it takes” for the bill to pass.

Now, this is a lot of information to take in but it is crucial to acknowledge the context of this policy, why it was suggested, and why such unprecedented measures have been taken to secure its passing. Just like the EU and the United States, there is no doubt that the UK faces a substantial problem with illegal migration. Last year, 52,530 irregular migrants were detected entering the UK, up 17% from the year before. 85% of these arrived in small boats and since 2014, some 245 migrants have tragically lost their lives in the Channel. Far more important to Sunak however, is the significant proportion of the electorate who he believes could be persuaded to vote Conservative again at the next election if he manages to get this plan in action. On this, it is nevertheless hard to claim that Sunak is anything other than extremely out of touch. Just 11% of voters cited immigration as a priority issue at the end of last year, the lowest level in two decades. Even worse for Sunak is that if this plan does actually come into force, he will all of a sudden be left with no-one else to blame and nowhere else to hide. All of a sudden, failing to fulfil one of the ‘five pledges’ central to his leadership will be entirely on him.

Now it cannot be denied that there is a genuine economic debate to be had on migration. Modern Britain has been built on immigration; from the post-war Windrush generation and as an out for our most serious economic problems ever since. Between just 2000 and 2011, according to a UCL study published in 2014, “the net fiscal balance of overall immigration to the UK between 2001 and 2011 amounts therefore to a positive net contribution of about £25 billion.” Immigrants were also 39% less likely to claim state benefits than natives during that time. Economists tend to agree with this pattern with The Migration Observatory stating in 2022 that “immigration had little or no impact on average employment or unemployment of existing workers”. Evidently then, the problems with the UK economy are not the fault of the comparatively small number of people driven to make tragic journeys across the channel. Only 6% of immigration to the UK in 2022 was attempted via the channel (most of those journeys would be unsuccessful). If the government wanted to limit migration (which is bizarre, given the labour shortage in countless areas of the economy) then it would be able to via other methods which aim to better control legal migration.

Likewise, if the UK government wanted to stop hundreds of innocent children dying in the channel and eradicate the criminal gangs at fault it could straightforwardly establish safe and legal routes to asylum from France. Similar efforts in Ukraine and Hong Kong have been rightly praised but the fact remains that there is absolutely no legal way for someone in a war-torn country to apply for asylum in the UK without crossing the channel. It would also be wholly disingenuous to suggest that those coming do not qualify for support: 92% of those who made the crossing between 2018 and 2023 applied for asylum and of those who received a decision, 86% were granted protection.

Has there been any immediate, observable change since the Rwanda bill has passed? Tragically not. On the 23rd of April, five more people lost their lives in the channel, crushed whilst French police watched on from the beach in Wimereux. On Wednesday alone, 700 people made the journey to bring the total since the bill’s passing up above 2000. The initial deal with Rwanda would see only 300 people travel there.

Perhaps the only tangible impact so far has been in Ireland, where foreign minister Micheál Martin has said that increases in asylum applications are as a result of the Rwanda bill passing in the UK. When the government in Ireland confirmed that they would be returning asylum seekers to the UK, as per an agreement in November 2020 and the UK Common Area Travel policy agreed more than a century ago, Westminster rebuffed it. Instead of honouring the agreement or talking compassionately about the hundreds who have set up camps in Dublin, Rishi Sunak claimed that it was an example of his policy changing immigrants’ behaviour to deter them from entering the UK (one of his own ministers later disputed this).

This comes as little surprise. Many have pointed out that having made the journey from war-torn countries, across multiple continents, the odds of being one of the 1% of people who are sent to Rwanda is unlikely to serve as much of a deterrent. Numerous interviews with prospective asylum seekers have rubbished the idea that it would make any difference; most fail to understand the complexities of the policy and the gangs profiting from illegal migration devote significant efforts to paint the scheme as nonsense.

It is in its impracticality and economic irresponsibility, where the Rwanda policy is at its most shameful and most disappointing. Whitehall’s official spending watchdog found in February that each and every one of the first 300 people would cost £1.8 million to send to the country. As Sophy Ridge pointed out to the Chancellor this week, every such payment could fund the education of 234 schoolchildren for an entire year.

For the government, this has never been about finding a workable solution. Instead, it is about standing behind aggressively emblazoned podiums, claiming to be “up for the fight” against human rights law, and showboating non-existent solutions. Instead of wholesale reform, investment, and the establishment of safe and legal routes in an attempt to save lives, Sunak’s government has chosen impractical showmanship.