Statute XI and student life: The evolving role of Oxford’s Proctors

The Proctors are one of the oldest and most fundamental parts of the University of Oxford and yet perhaps also the most obscure. Students don’t encounter the Proctors very often; and if they do, it is typically when receiving their coveted degree or a considerably less desirable summary of penalties for misconduct. There have been Proctors in Oxford since the thirteenth century, but unlike most institutions of the day, they continue to play a crucial role in the running of the University now and their activities have a direct impact on current student lives.

The Proctor’s Office is devised as a body independent of the Vice-Chancellor, tasked with upholding the University’s statutes. It is headed by a Senior and Junior Proctor and an Assessor on non-renewable yearly terms, meaning that every Hilary the position is newly filled with a different individual. Typically these are academics and not senior University administrators, who are elected by each college every thirteen years on an ongoing rota.

Cherwell has reviewed data from the past ten years of Proctor’s Reports to gain an insight into the workings of the Proctor’s Office within the distinct collegiate structure of the University. Our findings reveal that not only do Proctors continue to be heavily involved with many crucial aspects of student life but this impact is growing greater. While instances of sexual misconduct and harassment are increasing, the Proctor’s Office is still predominantly trained to deal with minor academic-related breaches.

As an institution, the Proctor attempts to provide centralised disciplinary action in the context of the extreme decentralisation fostered by the college system. In response, the office either relies on inefficient and inconsistent procedural methods or moves to centralise their processes to a potentially problematic point.

The following figures are derived from data in Proctor’s Reports published in the University Gazette, which provide data related to the Proctor’s Office’s annual activities. There is no standard format for these reports and some data may not be directly comparable across all 10 years. Proctorial years restart every Hilary Term.

Cherwell was informed that the most recent Proctor’s Report, which covers the proctorial year of 2023-24, is scheduled for publication sometime in Michaelmas Term 2024 despite Statute XI requiring that these reports be made at the end of every Hilary term.

Statute XI

In recent months, Statute XI has become the subject of extensive discussions within the University administration and across the student community after the University Council sought its revision in May of this year. The contents of Statute XI outline the University-wide rules and laws, defining the limits of acceptable conduct for students and other members of the University.

The investigation of both non-sexual harassment and sexual harassment occupies the bulk of the Proctor’s Office disciplinary casework on non-academic misconduct, following “engaging in any dishonest behaviour in relation to the University” and “engaging in offensive, violent or threatening behaviour or language”.

Across all seven years, the Proctor’s Office has reported an average of 5.6 cases of non-sexual harassment and 5.3 cases of sexual harassment, compared with an average of just 6.6 cases not classed as “harassment”.

Generally, the class of offence reported every year is not entirely consistent, for instance, a case of “disruption of University activities” only appears in the latest report from 2022-23. The type of breaches reported less than once a year on average include: “possession of drugs”; “breach of library regulations”; “engaging in action which is likely to cause injury or impair safety”.

This inconsistency may be partly explained by the rare incidence of these offences, yet it also suggests changes in the Proctor’s Office’s approach to the investigation of these breaches. Indeed, the decline of reported cases of “engaging in offensive, violent or threatening behaviour or language” may be correlated with the rise in cases reported as “non-sexual harassment”, however, this is remains ambiguious.

Regarding their jurisdiction for investigating breaches of Statute XI, the current Senior Proctor, Thomas Addock, told Cherwell: “In general, the Proctors deal with things in a University context, for example, University exams or allegations of misconduct between students at different colleges. If something happens within a college then the college will deal with it.” This jurisdiction on the margins of the collegiate system is not unique to the handling of student discipline and it defines the position of the Proctor’s Office within University life: they exist in the gaps between the colleges.

From harassment to plagiarism

Over the past five years, the Proctor’s Office has reported an average of 73 cases of academic misconduct, compared to an average of 18 breaches of the code of discipline.

The most common form of academic misconduct is reported to be “plagiarism”. For context, in 2022-23 “plagiarism” made up 67% of the total instances of academic misconduct, and 70% in 2013-2014.

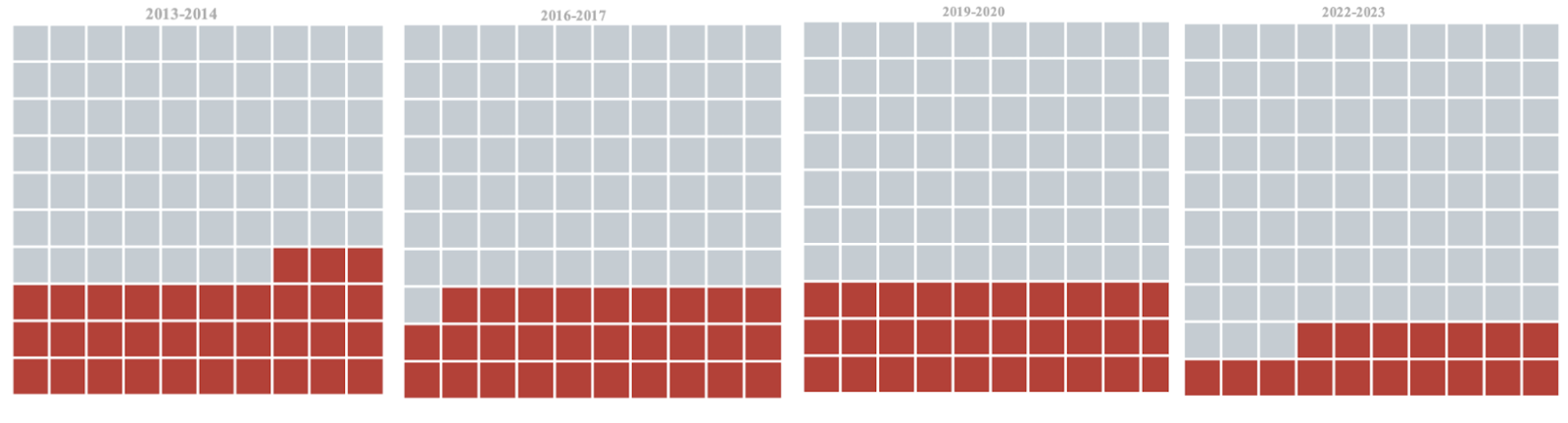

The largest proportion of the Proctor’s Office’s overall disciplinary caseload over four different proctorial years is concerned with “academic misconduct” (grey) rather than breaches of the code of discipline under Statute XI (red) (Figure two). These figures were calculated with the sum of total cases reported as “student academic misconduct” and “student non-academic misconduct” for every year. These exclude any additional cases that were listed as “legacy” or “ongoing” and it does not distinguish between those reported as “upheld” or “not upheld.”

The Proctor’s Office’s approach to resolving instances of academic misconduct appears especially inconsistent across this ten year period. The recourse to refer these cases to the Academic Conduct Panel is only reported in the period between 2016-17 and 2019-20, after this point it appears unused.

Every year some cases are referred to the Student Disciplinary Panel (SDP), yet an average of 2.8 cases were referred to the SDP in the five most recent years of reports compared to an average of 6.8 five years prior. Moreover, 2019-2020 stands out as the only year in which some cases are reported to have been resolved through ‘Proctor’s Decision’.

Additionally, in spite of the wide diversity of the Proctor’s caseload, the institution continues to partly rely on the judgement of the two acting Proctors for the majority of disciplinary cases, appeals, and complaints. In this regard, the Senior Proctor explained: “the Proctors are supported by an experienced team who do the hard work of investigations. They gather the relevant information on which the Proctors make the final decision.” In case of serious breaches, “the Proctors will look at the evidence and decide whether to refer the matter to the Student Disciplinary Panel.” This implies that despite the yearly turnaround in the head positions of the Proctor’s Office, it relies on an established staff of caseworkers.

Complaints and appeals

To further contextualise this range in the work of the Proctor’s Office, it’s important to note that figure two does not contemplate the significant amounts of academic appeals they receive every year. For 2022-23, the Proctors reported the receipt of a total of 124 academic appeals in addition to 84 reported instances of academic misconduct.

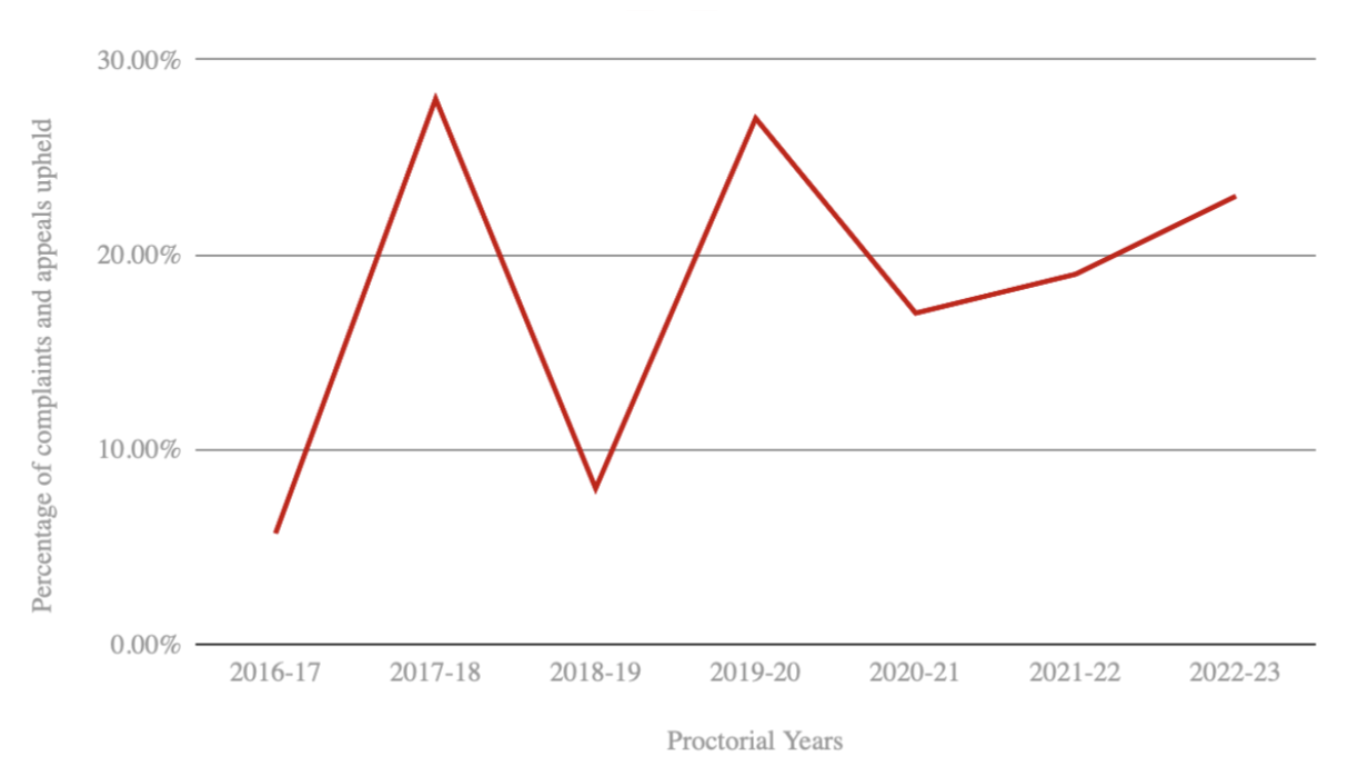

Figure three displays the percentage of students’ complaints and academic appeals upheld by the Proctor’s Office across the proctorial years of 2016-17 to 2022-23. These figures exclude the cases that have been shown as “ongoing” or “legacy” in the Proctor’s Reports.

As shown by figure three, there are some further inconsistencies in the proportion of complaints and appeals upheld by the Proctor’s Office throughout this period. There is no clear trend in the data until 2019-2020, when they plateau slightly. Indeed, in 2017-2018, 28% of cases were upheld contrasted by 8% the year after. Yet in the last three years, the proportion of upheld complaints and appeals has been steady.

In November 2017, there was a change in the University regulations, which introduced a three-step process – an informal first stage, a formal second stage and a review stage – for the handling of student complaints and appeals. This meant that a larger proportion of the majority of complaints were resolved without direct intervention from the Proctor’s Office. The introduction of this change may explain the evident variation in the percentage of cases upheld between 2016-17 and 2019-20. Implementation of an informal first stage of resolution demonstrates a desire for a partial decentralisation of this process.

There is no detail given in the most recent reports about the nature of student complaints, although some earlier reports cite reasons relating to “maladministration”, “discrimination”, and “teaching and supervision”. In contrast, academic appeals are explained to be largely “against decisions from Examiners” or otherwise related to “examinations” and “research student candidatures”.

Amendment controversy

The controversial amendment to Statute XI was first published in the University Gazette with an announcement of a legislative proposal from the University Council . Among the proposed changes, the Council sought to add a more detailed definition of “sexual misconduct” into the code of discipline.

A note accompanying this proposal explained that the changes were based on a decision of the University’s Education Committee to “widen the Proctor’s jurisdiction to investigate more cases of serious misconduct. As more of these often complex cases are now being reported, a range of legislative and procedural improvements are necessary to prepare for further increases that we expect to receive.”

Presently, it outlines that the offence broadly consists of “any behaviour of a sexual nature which takes place without consent where the individual alleged to have carried out the misconduct has no reasonable belief in consent”. The proposal included a further definition of both “consent” and what constitutes “sexual activity”.

Despite the fact that the Proctor’s Reports typically utilize the term “sexual harassment” and that this offense occupies a significant proportion of the Proctor’s caseload of non-academic misconduct, (figure two) there is no explicit definition of this term under Statute XI. Likewise, a clear distinction between what is termed “harassment” and what is referred to as “engaging in offensive, violent, or threatening behaviour” is not made explicit. This percentage shows no clear trend until 2019-2020, when a consistency seems to be established. Indeed, in 2017-2018, 28% of cases were upheld contrasted by 8% the year after. Yet in the last three years, the proportion of upheld complaints and appeals has been steady.

Furthermore, in light of the claim that “more of these often complex cases [serious misconduct] are now being reported” used to partly justify the original revisions to Statute XI, it appears that the proportion of cases of non-academic misconduct dealt with by the Proctor’s Office is not increasing in any significant (figure two). Yet, the average reported cases of non-academic breaches for the past five proctorial years, that are currently available, is 91, noticeably higher than the five years before that when it was 63.

Other amendments aim to change clauses related to student discipline more broadly: including a new requirement to “promptly inform the Proctors in writing if they have been arrested by the police and released under investigation (…) or if any of the foregoing appears likely to occur, and whether in the UK or abroad.” This and similar changes were criticised as “illiberal and antidemocratic” by an open letter circulated shortly after the announcement of the Council’s proposal. Before Congregation could meet on the 11th of June, the Council’s original proposal was withdrawn and the meeting cancelled.

Recently, Congregation met again on the 15th of October, and passed a resolution to form a “working group” for revising all proposed changes to Statute XI. This initiative was proposed by members of Congregation, and was formulated in response to the withdrawal of the original proposal. As such, this group will be made up of “relevant university officials, a student appointed by the Student Union, and five members of Congregation”. Importantly, it also seeks to “consult widely with members of academic staff … and students.”

Collegiate gaps

The Proctor’s Office is caught between the grey areas of Oxford’s collegiate system. It is torn between the changing needs of students and the demands of the central University administration, both of which require this institution to continuously adapt and evolve. This is no easy task.

The wide-reaching and diverse range of activities that this role demands can lead to further ambiguities, over stretched-resources, and possibly even foster suspicion on the part of the student community. In this vein, David Kirk, former Junior Proctor, concluded his demission speech by encouraging “the institution to think about ways to enhance the perceived legitimacy of the ways it handles both student and staff conduct. I encourage the institution to put even further thought into prevention.”