Hidden costs: The influence of donors on academic priorities at Oxford

Tucked away on a nondescript side street in North Oxford is Oxford University’s Dickson Poon China Centre, home to the Bodleian KB Chen China Centre Library. The £21 million facility is funded by some of China’s wealthiest individuals, from Dickson Poon, a Hong Kong billionaire businessman, to Daisy Ho, the daughter of a Macau-based billionaire who made his fortune from monopolising the Macau gambling industry. This is just one out of over 20 other buildings, scholarships, projects, and faculty positions in Oxford, named after and funded by Chinese individuals and organisations.

Over the last seven years, the University of Oxford has received up to £99 million from Chinese individuals and organisations. The majority of such donations are uncontroversial and the source country does not automatically make any funding problematic; several Chinese entities help financially support research projects, students, and museum exhibitions.

However, some of these donations stem from more contentious sources including companies facing sanctions from different countries and individuals involved in the Chinese government. This investigation explores the extent of China-linked money at Oxford University and its impact on research agendas, free speech, student welfare, and national security.

Analysing data acquired through Freedom of Information requests from the last seven years as well as from academic reports the full picture of Chinese funding at the University is exposed. Funding from Hong Kong-based companies and individuals are also covered in this investigation due to their links with China.

Threat of espionage

It is first important to consider why certain donations from China-linked entities can be problematic. In April of this year, the MI5 warned 24 universities, including Oxford University, about the possibility of espionage by foreign states targeting their research in a briefing to the universities’ vice-chancellors. MI5 did not name countries that it feared may attempt to gain information, but last year it also issued a warning which focused on China.

Following the MI5 announcement, the government introduced new measures, including increasing the transparency of research funding and government funding for universities to improve internal security. Researchers and university staff coming to the UK from certain countries, including China, must also now pass security clearing when applying for academic visas.

Academic freedom

Former head of the National Cyber Security Centre, Ciaran Martin, stated in April that British security services were concerned about the targeting of university staff to influence research, and argued that scholarships awarded by China or China-affiliated organisations are often suspected of exerting such influence.

UK-China Transparency (UKCT), a think tank, found evidence based on official translated documents that programmes co-governed by the CCP, such as China Scholarship programmes and Confucius Institutes, may pose a threat to academic freedoms. According to UKCT, these programs involve “discrimination, restrictions on freedom of speech, obligations on Chinese university members to inform on their peers whilst in the UK, and other elements inimical to academic freedom and the protection of free expression.”

Sam Dunning, director of UKCT, told Cherwell there was an “ever-present threat of CCP action against individuals, which hangs over thousands of Chinese students at Oxford, as well as academics and even administrative staff from China.”

He stressed that the CCP’s influence on universities does not just prove problematic for freedom of speech but, more specifically, that “it is the force that prevents freedom of speech and academic freedom for tens of thousands of students and academics in the UK – those from or with family in China.”

A scholarship awarded by the Chinese Scholarship Council – an organisation run by the Chinese Ministry of Education – provides full funding and a maintenance loan to up to 20 mainland Chinese students per year studying for a DPhil in Oxford University.

According to UKCT, to receive this scholarship, students must undergo a rigorous review of their political ideology and be assigned to two guarantors, usually family members. Additionally, if granted a scholarship by the Chinese Scholarship Council, scholars are required to “support the leadership of the Communist Party of China”, “love the motherland”, “maintain a sense of responsibility to serve Sam Dunning, director of UKCT, told Cherwell that there was an “ever-prthe country”, and “have a correct worldview, a correct outlook on life, and correct values.”

Due to these restrictions, there have been calls for top UK universities to reject such scholarships. Russell Group universities declined, expressing fear that doing so would harm foreign relations. A spokesperson for the University of Oxford told the Daily Express, “We take the security of our academic work seriously, and work closely with the appropriate government bodies and legislation.”

Amnesty International UK said earlier this year that Chinese students in Europe, the UK and North America are ‘intimidated, harassed and silenced by the Chinese authorities as part of a sinister pattern of transnational repression.’

Sacha Deshmukh, Amnesty International UK’s Chief Executive, said, “The Government and UK universities need to understand the dangerous realities Chinese students face from China’s transnational repression.” The University of Oxford did not reply to Amnesty’s comment request.

The University seems to understand these dangers, and undergraduates studying politics are warned about saving content relating to China on their computers.

Furthermore, those taking the ‘Politics in China’ paper are required to sign a legal document acknowledging that they understand the risks involved due to Chinese extraterritorial national security legislation.

The scale of funding in Oxford

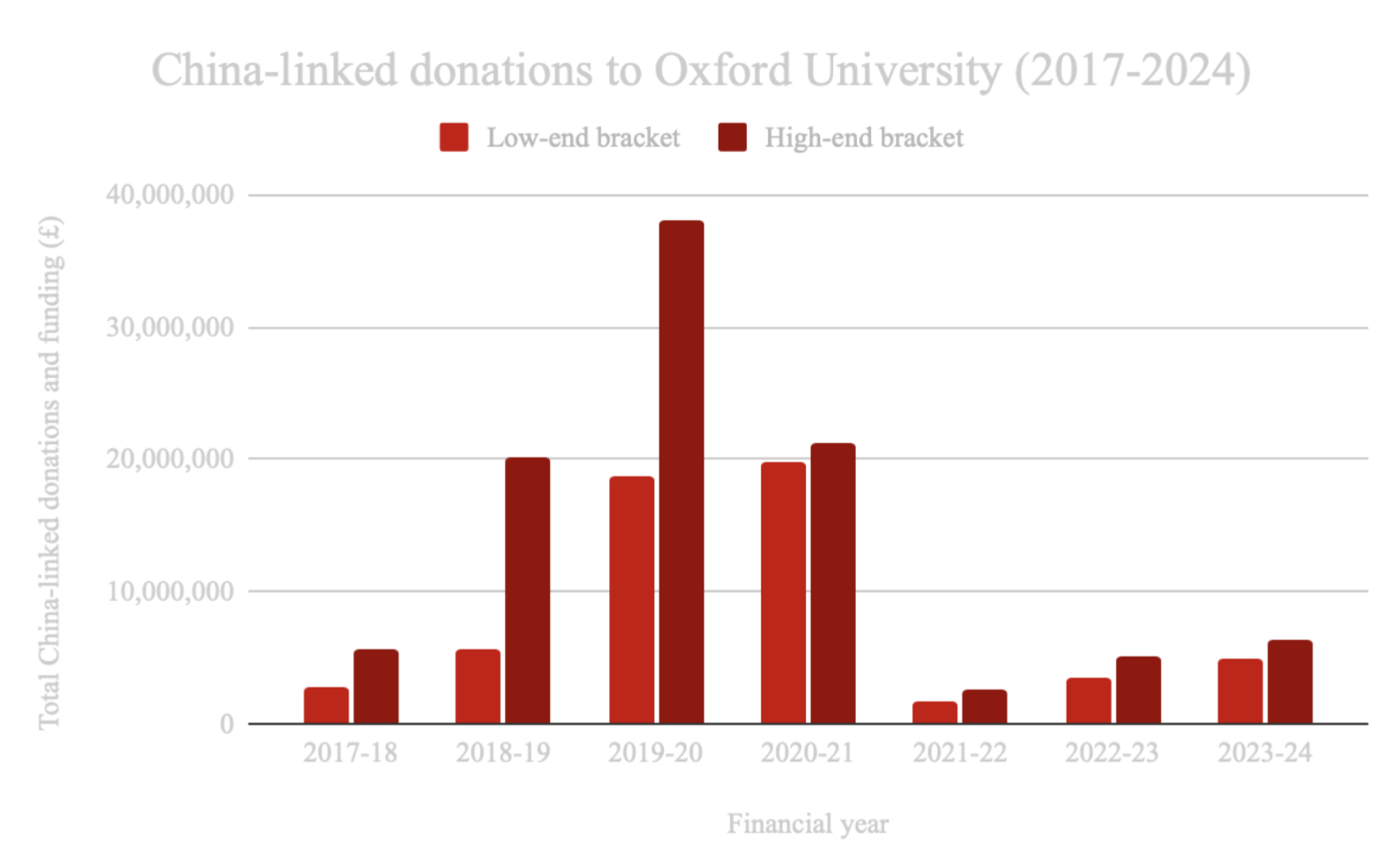

From 2017 to 2024, China-affiliated individuals and organisations have given the University of Oxford a total of between £57 million and £99 million. This total consists of £42 million to £58 million in research funding and between £15 million and £41 million in donations and gifts.

The large range of amounts given is due to the University’s choice to provide bracketed figures. This means that for most donations, they do not state the specific amount but give a minimum and maximum amount that it falls between.

A report into the strategic dependence of UK universities on China, published by think tank Civitas, noted that data in this format tend to contain “extreme divergences” and, in any case, do not provide a clear image of the actual magnitude of money involved.

The 2019 to 2020 financial year saw the peak amount of Chinese funding, according to the maximum bracket estimate. This is also when there was the largest disparity between the possible lowest and highest amounts with the maximum estimate (£38 million) being double the lowest estimate (£19 million).

According to Civitas, between £5.7 million and £6.6 million was given to Oxford from Chinese military companies sanctioned by the US and companies either linked or widely suspected of being linked with the Chinese military from 2017 to 2022. This constituted around 15% of all money from Chinese entities to the university.

Academic institutions

It’s often obvious to Oxford students where the funds go – they only need to pay attention to the titles of buildings, positions, and faculties around them. But much less is known about the people and institutions behind these names.

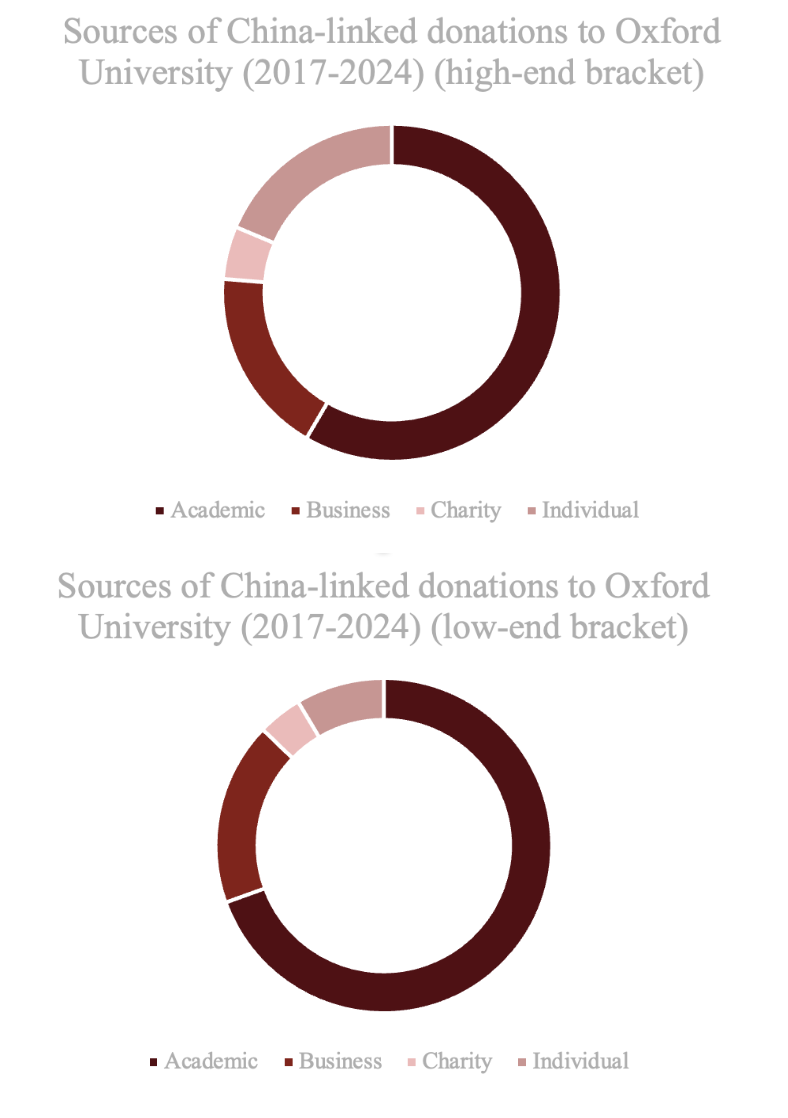

The three major categories of China-linked donors to the University of Oxford are academic institutions, businesses, and individuals (figure two). As mentioned, the vast majority of these donors are honest and reputable sources, choosing to donate their funds to the University for the same reasons as donors from all other countries.

Academic institutions, such as Chinese universities, have been the most common type of China-linked donor to the University of Oxford and they make up 58% to 68% of all donations and research funding originating from China since 2017.

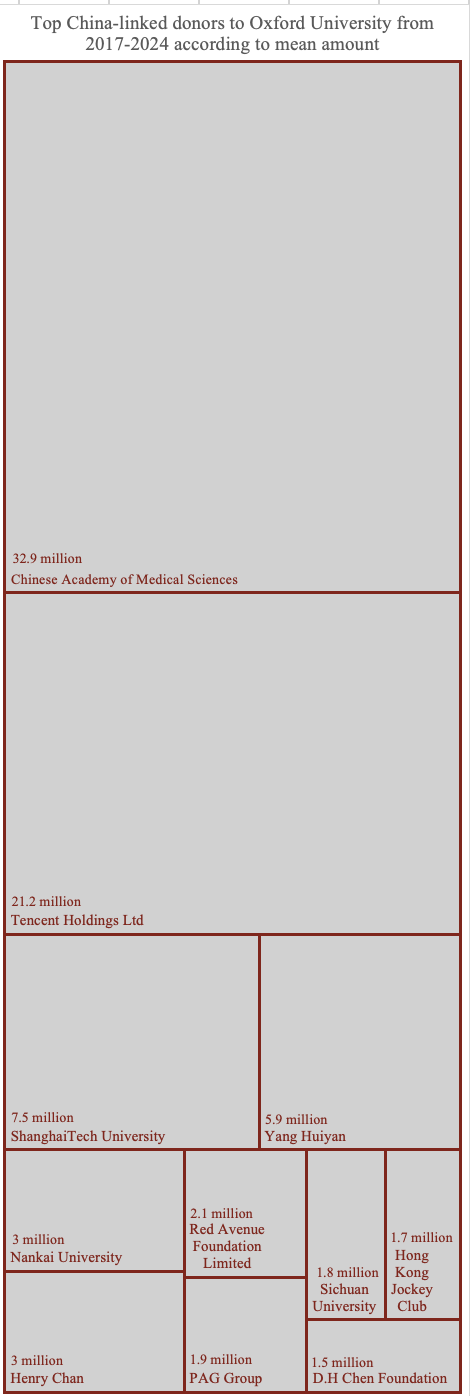

Moreover, the two largest individual donors over the past seven years are both academic institutions, with the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (CAMS) taking the top position and giving £28 million to £37 million during this time period (figure three). The institute’s single largest donation was £13 million, given in the year 2020 to 2021. The donations were directed to the CAMS Oxford Institute at the Nuffield Department of Medicine.

ShanghaiTech University was the second-largest donor, having given between £5 million and £9.9 million since 2017. Their donations to Oxford aim at “establish[ing] cooperative relationships” between the two universities. First-year students at ShanghaiTech are required to perform one week’s worth of military training. The Guardian recently described how “the growing emphasis on military training for civilians reflects a heightened nationalism in today’s China under Xi”

Sichuan University, the eight-largest donor, gave £1.8 million between 2017 to 2024 and has been designated as ‘Very High Risk’ by a report from the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI) due to its links to the Chinese military. Freedom of Information requests revealed its donations have been directed toward biomedical research. The ASPI report notes the institution’s close relationship with the Chinese Academy of Engineering Physics (CAEP), China’s primary nuclear warhead research facility.

Business donors

In 2020 to 2024, business donations were the second-largest category of donor, accounting for 22% to 28% of donations (figure two). This represents an increase of 10 to 17 percentage points since the period 2017 to 2020. Three of the most prominent businesses to donate to Oxford University are Tencent, Huawei, and Baidu.

Among other technological products, Tencent operates WeChat, and the conglomerate has been accused of significantly aiding the Chinese authorities’ suppression of civil freedoms through the intense regulation of the use of their products. Tencent has been approved as an “appropriate donor” by an independent university committee that vets donors and has made several donations to computer science research.

Article 7 of the Chinese National Security Law requires companies such as Tencent to cooperate with the government on matters deemed relevant to “national intelligence”, which can include censorship and data sharing. Private enterprises with more than three Chinese Communist Party (CCP) members are also required to have an in-firm branch of the party. According to the East Asia Forum, “the private sector is still seen as a frontier for party-building” and more specifically, Company Law in China requires that these in-firm party units carry out the activities of the CCP.

Huawei, a Chinese multinational technology company, is also subject to this rule. Since 2017, the world’s largest smartphone manufacturer has donated between £500,000 and £1.2 million to Oxford University. Huawei has faced a wave of sanctions from several states, including Germany, Japan, the USA, and Australia, for its links to the Chinese military; evidence that its technology was being used in the mass surveillance of Uyghur Muslims in Xinjiang detention camps; and accusations of intellectual property infringement.

The UK has blocked Huawei as a vendor of 5G networks due to perceived cyber security and espionage risks. Huawei denies all allegations of misconduct. The University’s records on rejected donations since 2017 reveals it has recently refused to accept funds from Huawei. The University states this is due to them wanting “to pause negotiations concerning any new projects and as such not accept funding for new projects.”

Between 2017 to 2024, Baidu, a Chinese technology company specialising in internet services, contributed between £100,000 and £250,000 in research funding to Oxford University to support technological research, including 3D machine perception for autonomous driving cars. Baidu’s search engine censors certain content, blocking results for Xi Jingping as well as for Vladimir Putin, according to recent research from the Citizen Lab.

Individual donors

Individuals are the third largest category of donor, although their corresponding proportion has decreased from 15% to 26% in 2017 to 2020 to 3% to 4% in 2020-2024 (figure two). However, these donors still provide significant amounts of funding to the University.

Jesus College’s Cheng Yu Tung Building was partially funded by a £15 million donation from Hong Kong property developer Henry Cheng Kar-shun. Cheng Kar-shun owns a highly prominent business empire and is Chairman of New World Development, which the Financial Times recently reported as increasingly reliant on the mainland China market.

Cheng Kar-shun was a member of the twelfth Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC), a political advisory body in China, composed of individuals from different fields, including business and academia. It exists to advise government bodies on political and social issues. The CPPCC has no real legislative power, but is subject to the direction of the CCP. Regarding Cheng Kar-shun’s donation, Jesus College told Cherwell: “The College named the building after the Cheng family in gratitude for their generosity. The donation was not conditional.”

The biggest individual donor, and third biggest donor overall to Oxford University since 2017, is Yang Huiyan, Vice-Chairwoman of Country Garden, one of the largest private real estate developers in China. Before the recent Chinese property crisis, Yang was the richest woman in Asia and is married to Chen Chong, the son of a senior provincial official. An article by Forbes noted that over 90% of China’s 1,000 richest individuals are members of the CCP.

China Oxford Scholarship Fund

A large proportion of donations from Chinese entities also go towards supporting scholarships. This includes the China Oxford Scholarship Fund (COSF), which supports students from China, Hong Kong, and Macau in their postgraduate studies at Oxford, with scholarships awarded to students who show academic excellence, financial need and a “commitment to contributing to the development of China.”

Johnny Hon, Hong Kong businessman and founder of conglomerate the Global Group, is a prominent donor to this scholarship. As with Cheng Kar-Shun, Hon is a member of the CPPCC. Moreover, according to The Times, Hon is a former chairman of the Kim Il Sung-Kim Jong Il Foundation, which seeks to promote the state ideology of North Korea, known as Juche.

Lord Christopher Patten, the last Governor of Hong Kong and the outgoing Chancellor of Oxford University, is described by the Fund as a longtime supporter. This June, he invited COSF scholars to his home for a garden party in honour of his retirement.

What about Oxford?

Oxford is far from being the only university that has such engagements with China and, comparatively, since it is more financially independent than other universities, it is not as reliant on particular donors. In 2022 to 2023, only 5.6% of the University’s income was from international fees, compared to a UK average of 23%. Despite this, the University continues to accept millions of pounds from Chinese entities every year.

Across the UK, universities received £125 million to £156 million from Chinese entities during the period 2017 to 2023. Of this sum, £36 million to £51 million was from Chinese entities subject to US sanctions or connected to the Chinese military. This constituted 30% to 33% of the total amount of money received, compared to Oxford’s 15%.

In an interview with The Telegraph, Patten spoke about UK universities’ dependence on China, warning that Chinese authorities may pressure academics to avoid certain topics and that students’ behaviour is being reported on. However, Patten also stressed that universities should not treat their large Chinese student bodies differently to others out of “fear of being ticked off by the Chinese government.”

Johnny Hon said in response: “When I established the Johnny Hon China Scholarship, I said: ‘Much may change in the next ten years but the need for mutual understanding, and the opportunities it can open up, can only grow.’

“I still hold that view. The scholarship was focused on law, politics and international relations and aimed to increase understanding of western, and particularly UK, perspectives on these important subjects.

“I find it somewhat sad that anyone might seem to impugn the motives and integrity of more than 20% of the world’s population in such a sweeping fashion. If there are specific instances or accusations of such nature, then the onus should be on the accuser to present the necessary proof.”

The University of Oxford said in response: “All Oxford University research and teaching is academically driven, with the ultimate aim of enhancing openly available scholarship and knowledge. Funders have no influence over how Oxford academics carry out their research, or on our teaching and robust policies on academic freedom. All donors are subject to our policies on the acceptance of gifts, and all significant donors and funders must be approved by the University’s Committee to Review Donations and Research Funding, which is a robust, independent system taking legal, ethical and reputational issues into consideration. We take the security of our academic work seriously, and work closely with the appropriate Government bodies and legislation. Much of our overseas collaborative research addresses global challenges such as climate change and major health problems where international involvement is important in delivering globally relevant solutions.”