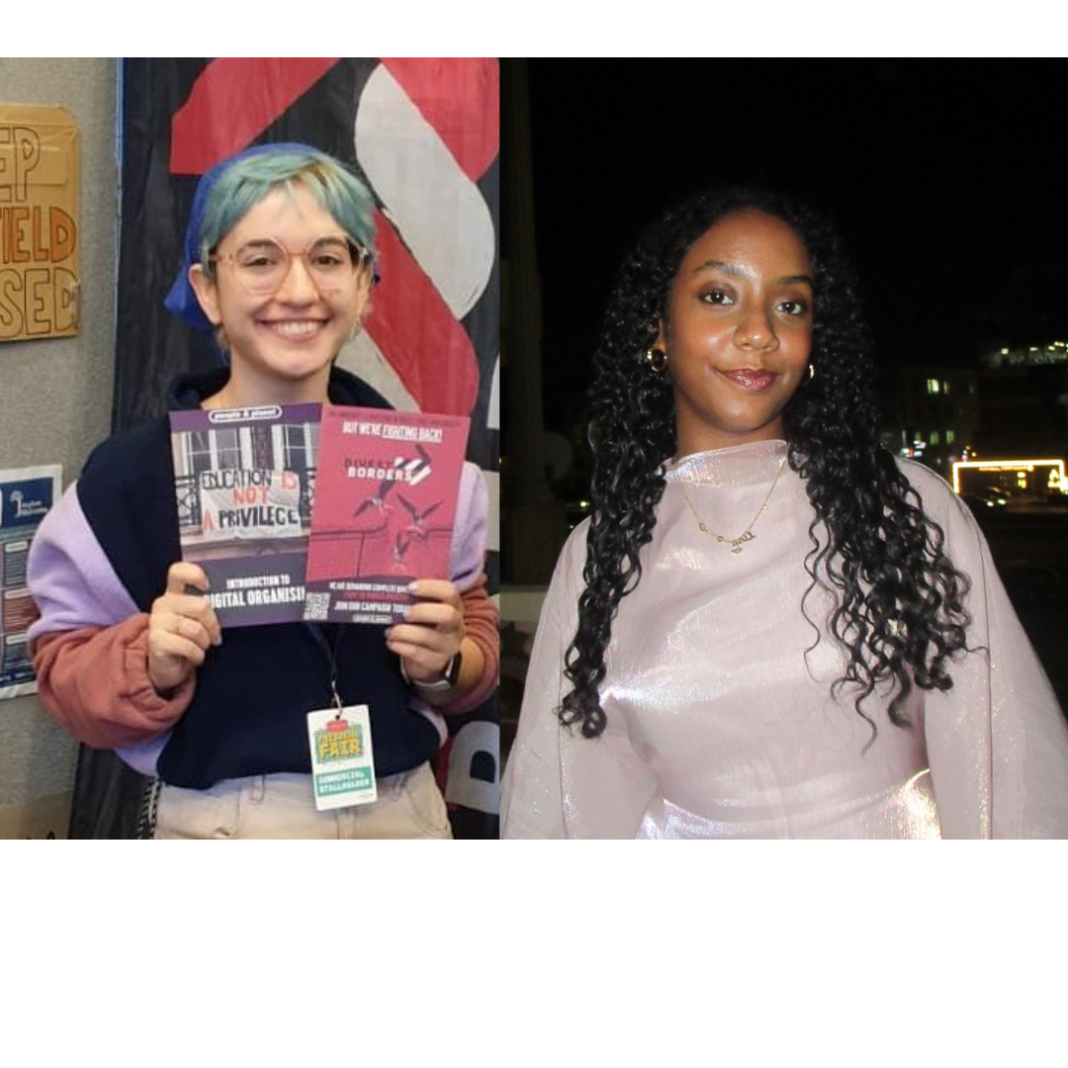

With an increased focus on divestment over the past year, Cherwell sat down with two student activists involved in this work, Diana Volpe and Lina Osman. They are the presidents of Divest Borders and Student Action for Refugee (STAR) respectively – Lina serves as co-president of STAR with Tala Al-Chikh Ahmad.

We started with a conversation about what these groups do. Part of STAR’s work centres around direct volunteering: “Students go out to volunteer either on casework, which is on-the-ground stuff of helping clients sign up for universal credit, GPs, and so on; or they volunteer with the Youth Club, which is really great as well – you just get to hang out with young people and help out.” On the campaigning side, Divest Borders and STAR are closely linked. Lina told Cherwell: “[We aim to] make sure that as a University, we divest from the border industry. There’s also the Keep Campsfield Closed Coalition that we’re a part of. Campsfield is a detention centre in the north of Oxford. It was previously closed, the government is trying to reopen it, and so we’re campaigning with the coalition to try and keep it closed.”

The concept of divestment, particularly border divestment, has been something that’s only recently come into focus. With Divest Borders Oxford being launched in 2021, Diana talked about the initial difficulties: “For absolutely horrible reasons, divestment has [now] become a lot more known by people, but when I started, it was really hard to even explain the point of divestment and why it works. I spent most of my time explaining to people what the border industry even is, and it’s something people have never really thought about or talked about.” For Diana, this activism was closely linked with their academic work: “My PhD in particular is about the ways in which these types of outsourcing operations of migration control get legitimised in the public sphere – it’s something to that feels so insane to me, yet it’s so normalised that it’s not even controversial on a public level. So that’s the main question of my PhD: how do situations like these, that include a lot of human rights abuses, get completely normalised?”

Both Lina and Diana talked about a kind of disconnect they felt between their academic work and the real-life issues occurring in their field. Diana described it as “the ‘ivory tower’ feeling of it all”, while Lina talked about struggling with her degree conceptually, “… especially during Trinity, when the encampment was going on, and yet I’d spend the majority of my day studying stuff that I felt was so useless, so baseless.” For her, the volunteering she got to do through STAR at Asylum Welcome “was the only time when I kind of got the chance to touch down with the world… When I applied to be president [of STAR], it was kind of like trying to counteract my degree in some ways, and base it in the world.”

Diana had a similar basis for starting Divest Borders: “I decided to act locally because it’s a place in which I had the power to do something. I found this new campaign that was started by People and Planet called Divest Borders, and it seemed like a great way of raising awareness using my research and my expertise, but also using the power that I had as a student in Oxford.”

However, both had also found that using this power as a student to enact change wasn’t particularly straightforward. In attempts to contact the University administration, Diana found that their work wasn’t considered “high-profile [enough] to be receiving hostility from the University, but it’s just completely irrelevant to them.

“When we went through staff from the University and College Union (UCU), they just told us ‘This is not a legitimate channel to bring the issue to us, you need to do it this other way’, [a way] which required a lot of manpower which I did not have. It’s been really tough to convince enough people to be involved.”

Lina notes that the response to STAR has been slightly more complicated: “…as opposed to other, what the University might view as more ‘controversial’ [campaigns], the University can be very supportive insofar as [being] like ‘oh, obviously you should fundraise for refugees, or you should go out and spend your time volunteering’, but when it comes to the campaign-side, like putting out a statement against Campsfield, or divesting from the border industry – you get a lot more pushback. So they’re very happy to be tokenistically allies, but not in any material sense, which makes it really difficult, because I think then our work becomes, at times, stunted by the University.

“I want to give them some credit – I think they’ve done good stuff, I know Balliol has sanctuary status, I know other colleges have it – there is some positivity. I think the issue becomes that the University administration, plural, as an entity, has pushed back, not necessarily individuals within that administration.”

These structural limitations of the University, she argues, are simply unrealistic: “There needs to be more of an air of acceptance of the fact that Universities are generally very active spaces, and University students are very active people; these are always grounds for activism. Universities don’t necessarily have to support the content of the activism, but I think just supporting the framework is a step: let people put up posters in your JCR, or let people have meetings with you about what they want to talk about, or things like that.”

STAR and Divest Borders are ingrained in the work of the wider Oxford community as well. Diana talks about connecting with the Campaign to Keep Campsfield Closed: “I wanted to make sure [Divest Borders] wasn’t just something I kept within the University, but also had to do with local issues and populations, and the community that lives here, and has been doing this type of abolitionist work for decades. They can really bring a lot of incredible knowledge. It’s something that I really appreciate, because they are really open to hearing new ways of doing things and passing on the generational knowledge of organising and activism.”

Diana also points out specific companies within this community who Divest Borders aims to call out: “A lot of these organisations are smart about the way in which they do things, so they do a lot of what I usually call ‘rights-washing’ – they invest in other types of work. An infamous one in Oxford is Serco, because apart from the fact that [they] run private immigration removal centres for profit, they also started getting involved with managing several things around the COVID crisis, and at the moment, they run all the leisure centres in Oxford.”

The work of these organisations also extends beyond the town. A group of students within STAR went to volunteer with an organisation at the Grand-Synthe refugee camp. The work first came about when Roots, an NGO working in the camp, reached out to Lina and Tala: “The organisation we were working with focuses on WASH, which stands for water, sanitation, hygiene. They run a water point that they clean twice a day, showers, toiletries, but also a community hub. It’s an unofficial refugee camp, which means there’s no government control. It used to be the Calais Jungle, up until 2016 – it was huge, part of it burned down, part of it was bulldozed by the government – but obviously that didn’t mean that people left.”

When I first asked Lina about her reflection on the trip, she gave a hesitant response: “The actual trip… it was good.” She laughed at the uncertainty in her tone. “No, I’m sorry, that sounded really bad. On multiple occasions since I’ve come back, people have asked me that question and I struggle to describe it; I don’t know what the right word is. Because there wasn’t quite anything ‘good’ about it in the sense that it was cold, and it was wet, and one day, there was a gunshot alert at camp, one day there was a fight that broke out, one day there was a man with a machete, and we were sleeping in a warehouse with 14 other people. There was nothing quite objectively ‘good’ about the experience, but maybe ‘fulfilling’ is the word? We did a lot of work that I think was good work.

“I think for me and Tala as well, because we both come from a refugee background, it was quite a heavy experience – I mean I’m Sudanese, and that’s, I think, at the moment, the biggest displacement crisis in the world, and there were a lot of Sudanese people there, and there were quite a few days where that was quite overwhelming.”

Along another coastline, Diana was also working with a volunteer organisation, Sea-Watch, over the winter break. They told Cherwell: “Ever since 2013, there’s been a lot of NGOs doing civil search-and-rescue. They often patrol the areas of international waters that are not covered by any search-and-rescue zone, mostly around Italy. They find distress cases of people that are trying to reach Italy and just perform rescues. These are usually people that the Italian coast guard refuses to reach, and most importantly, what [these NGOs] want to avoid is for people to be pulled back to Libya.

“It was really eye-opening: I feel like even if you know a lot and read a lot, there’s nothing like being there in real life and realising the insanity of border violence in the Mediterranean – when you perform a rescue at four in the morning and you find a boat that’s been at sea, unable to make way, for three days, and there’s 60 miles of nothingness in every direction. It’s really insane, the way we’ve set up the whole ‘Fortress Europe’ system. And to think – in the UK, it’s even more violent, because we’re talking about 20 nautical miles of the Channel, and people still capsize and drown. It’s really not acceptable.”

When asked about what students could do to help, more dialogue and conversation about refugees and the border industry was high up on both their lists. “Militarised borders are not a very old phenomenon at all,” Diana explained, “but it’s become so entrenched in the way that we organise, and people really struggle to break away from it.”

Lina’s suggestions were in a similar vein: “These aren’t necessarily issues that people know anything about – I think the border industry is not something people know as much about as they should.

“If you’re willing to dedicate your time, sign up to volunteer, sign up to help us campaign, come to our protests, demos. Tell your friends about it, anything really, follow our Instagram, engage with our stuff. But also as much as we do good stuff, these are active issues: donate your money to refugees, donate your time directly to refugees, I think that’s really important as well.”

University reply: As a University of Sanctuary, we are committed to creating a space of welcome and inclusion for refugees and people from displacement backgrounds. Over the past couple of years, we have greatly expanded the number of refugee scholarships offered across the University, created the Oxford Sanctuary Community to provide cohort support for students and staff from displacement backgrounds, and established a range of collaborations with local organisations working with sanctuary-seekers.

As a University, we aim to avoid taking political positions. Our aim is to create an environment within which our academics and students can freely express their own views within the boundaries of free speech, but it is not the central University’s role to be an arbiter in political debates.

With respect to Campsfield, the University has met with representatives of the Keep Campsfield Closed Campaign. Many members of the collegiate University have signed the Keep Campfield Closed open letter in an individual capacity. When it comes to divestment, the University’s Ethical Investment Representations Review Subcommittee (EIRRS) exists as the relevant committee to consider questions relating to university-level investments. It is currently undertaking a review of aspects of the University’s investment policies.

Serco reply: We totally reject the suggestion that Serco ‘rights-washes’ running of private immigration removal centres for profit by getting involved with management of the COVID crisis and running the leisure centres in Oxford. It is an uninformed comment without foundation that ignores the facts. Serco supports governments globally, and our services span immigration, defence, space, citizen services (which included our work in support of the Government on COVID), health, and transport and Community Services (including the management of over 50 leisure Centres around the UK). With over 50,000 employees worldwide, we bring together the right people to run critical public services on behalf of our government customers efficiently and effectively. Our breadth of expertise underpins our commitment to helping governments respond to complex issues and provide essential services to their citizens. Serco has a long history of providing immigration services in the UK, and currently offers accommodation and support services to more than 40,000 people seeking asylum in communities across England.