Oxford’s political societies cultivated generations of MPs and PMs. In an era of rising populism, a tour of their drinking events finds a drifting elite with few ideas.

It’s a well-worn cliché that Oxford is the place where future politicians are made. The student party societies here are where Prime Ministers-to-be from Margaret Thatcher to Liz Truss first cut their teeth. But as the size of party memberships continue to fall and a populist surge increases the currency of being an ‘outsider’, what is the role of Oxford’s political societies in shaping British politics? Are these societies ready to grapple with modern politics or are they just another antiquated Oxford tradition? To find out, I spent four evenings this Trinity term drinking with the University’s wannabe politicians.

Beer and Bickering – Oxford Labour Club (OLC)

On a Saturday evening in early May I walked into St Anne’s JCR to a gathering of no more than 20 people. I’m starting with the party in power as I want to see how they react to the numerous announcements from the government over the Easter vacation. From the decision to slash Universal Benefit rates to Keir Starmer’s new conviction that trans women are not women – coinciding with recent interpretation of the Equalities Act by the Supreme Court – are student Labourites joining the government as it shifts to the right?

One quick notice is made before we get going. The welfare secretary stands up and implores us to avoid discussions of controversial ‘foreign affairs’ (translation: for the love of God don’t start talking about Israel-Palestine). One can understand why they are apprehensive, given Labour’s history of antisemitism controversies. But it also establishes that there will be strict parameters on tonight’s conversation.

There is a distinctly dour mood this evening and the cause becomes clear once the discussion of the first motion (‘this house would deprioritize economic growth’) gets going. Speaker after speaker gets up and expresses their despair with the economic policy of Starmer and Co. From the obsession with growth (“or whatever it is we’re doing,” as one man puts it), to the scrapping of the winter fuel payment (since reversed), Starmer’s decisions have distinctly dampened the excitement OLC members no doubt had this time last year.

As for what they would do differently? It’s less clear, but the need to reign in inequality and tax wealth are met with nods of approval. During the break I point out to one member that the arguments made sound a lot like the Greens’ positions, and ask why he doesn’t support them instead? “Ah well, I’m in too deep for that now,” he tells me.

During the discussion of the second motion, I’m less taken by the content of the arguments (the consensus is pretty clear that there shouldn’t be ‘a national religion’) than by who is doing the arguing. The speakers are almost all men. I point this out to a member, and he grimaces, explaining that it’s long been an issue for OLC. Although the social secretary and both co-chairs this Trinity are women, he tells me that Beer and Bickering remains “a sausage-fest”.

The rest of the evening passes uneventfully. The final motion (‘this house, as the Labour Party, would encourage strikes’) was again met with consensus: strikes are an essential tool but a last resort. As I walk home past drunken May Ball goers, I can’t help feeling that the lack of discord is somewhat by design. There’s clearly a lot of discontent with the Starmerite project, but OLC’s only response is apparently to gather once a week to collectively agree on uncontroversial principles. A lack of imagination, or more likely an eye on an internship in the party, seems to nip in the bud any interesting and (God forbid) controversial discussion of real policy alternatives.

“There’s clearly a lot of discontent with the Starmerite project, but OLC’s only response is apparently to gather once a week to collectively agree on uncontroversial principles.

Port and Policy – Oxford University Conservative Association (OUCA)

A week later, I made an uncertain attempt at putting together a ‘lounge suit’ as per the Oxford University Conservative Association’s dress code. This feels like an unnecessary extravagance, given the venue: a dilapidated scout hut in New Marston.

I’m greeted by an American post-grad in an expensive looking three-piece suit who proudly explains that he will be ‘speaker of the house’ for tonight’s discussion and promptly returns to doing his ‘vocal warm ups’ (“BA – BA- BA!”). I shuffle over to the side of the room, picking up a flimsy plastic port glass as I go, and watch as the OUCA regulars trickle in. The men are all strikingly similar: under 6 foot tall, dressed in chinos, blazers and trainers and with precisely combed hair. More interesting, though, is the fact that they don’t dominate the makeup of attendees: the room is far more diverse in gender and ethnicity than OLC. It’s also substantially better attended, which is impressive for a party with the worst national polling in its history, and given how far out of the town centre we are.

I get to chatting with attendees. They quickly suss out that I’m new and I have bought membership (as I will for all the societies I visit) which lands me on the receiving end of some concerted networking efforts. Whereas with Beer and Bickering the conversation was pretty laid back, here I’m constantly asked for what my Instagram handle is and whether they’ve seen me before at the Oxford Union (they haven’t). It’s like everyone has just finished How to Win Friends and Influence People and is keen to put it into practice: “So tell me, Stanley, what EXACTLY is it that makes the food at Teddy Hall so great?”

I’m relieved, then, when the ‘speaker’ bellows out that the first motion of the night will begin. I look around, waiting for the room to fall quiet, but the conversation continues as if nothing had happened. Instead, the participants in the debate begin screaming their arguments at the top of their lungs to a room which is evidently not listening. I move closer, trying to make out what they are saying, but I can’t for the noise of conversation. The three debaters resemble the street preachers on Cornmarket Street, shouting at distinctly uninterested passersby.

“What I witnessed was a small elite jostling for an inheritance that’s long been spent.

Unable to glean anything from the participants, I begin asking questions of those around me. How do they feel about the recent local elections, in which the Conservatives lost 674 councillors? “I don’t think people here realise that Reform is an existential threat,” one member tells me once it’s just the two of us. It’s hard not to agree with his assessment. In all the conversations I have, the national party – or indeed politics – is hardly mentioned. When I ask people why they are here, they often appear a bit sheepish. They claim that they just fell into it, that it’s quite addictive, that it’s for the social side of things. Even at OUCA, being a Tory isn’t particularly cool.

This is with the exception of one man, who points proudly to his tie displaying the emblem of the Heritage Foundation – the think tank central to Donald Trump’s election victories and behind the controversial Project 2025. I ask how he feels about the current ‘DOGE’ federal spending slashes, in particular on USAID. He has mixed feelings, there are some things he wishes they’d keep, “but others I’m happy to see go, like trying to get rid of HIV”. I wonder if I misheard him over all the shouting: “sorry, did you say you don’t want them to fund AIDs treatment?” He gives me a confused look: “Of course”.

Before I have time to ask further questions, the debate, occurring primarily between two blokes (one of whom is brandishing a large stick that makes him resemble a Tory Gandalf) finishes. The members gather for a rendition of ‘God Save the King’ (they all know the second verse), followed by an equally boisterous recital of ‘Jerusalem’, and leave to clamber into Ubers.

I walk back to Cowley, lost as to what to make of the evening. I would comment on the motions chosen, the arguments made, but I couldn’t hear a word of it. If the voters went to the polls tomorrow, all evidence suggests that the Tories, already much reduced, would be decimated and it seems that the OUCA members wouldn’t bat an eye. Instead, the whole thing is just another fixture in the Oxford Union social scene: a rite of passage for ambitious Christ Church freshers and a place for forming useful connections. The state of the Conservative Party, currently barrelling towards irrelevancy, is merely an afterthought.

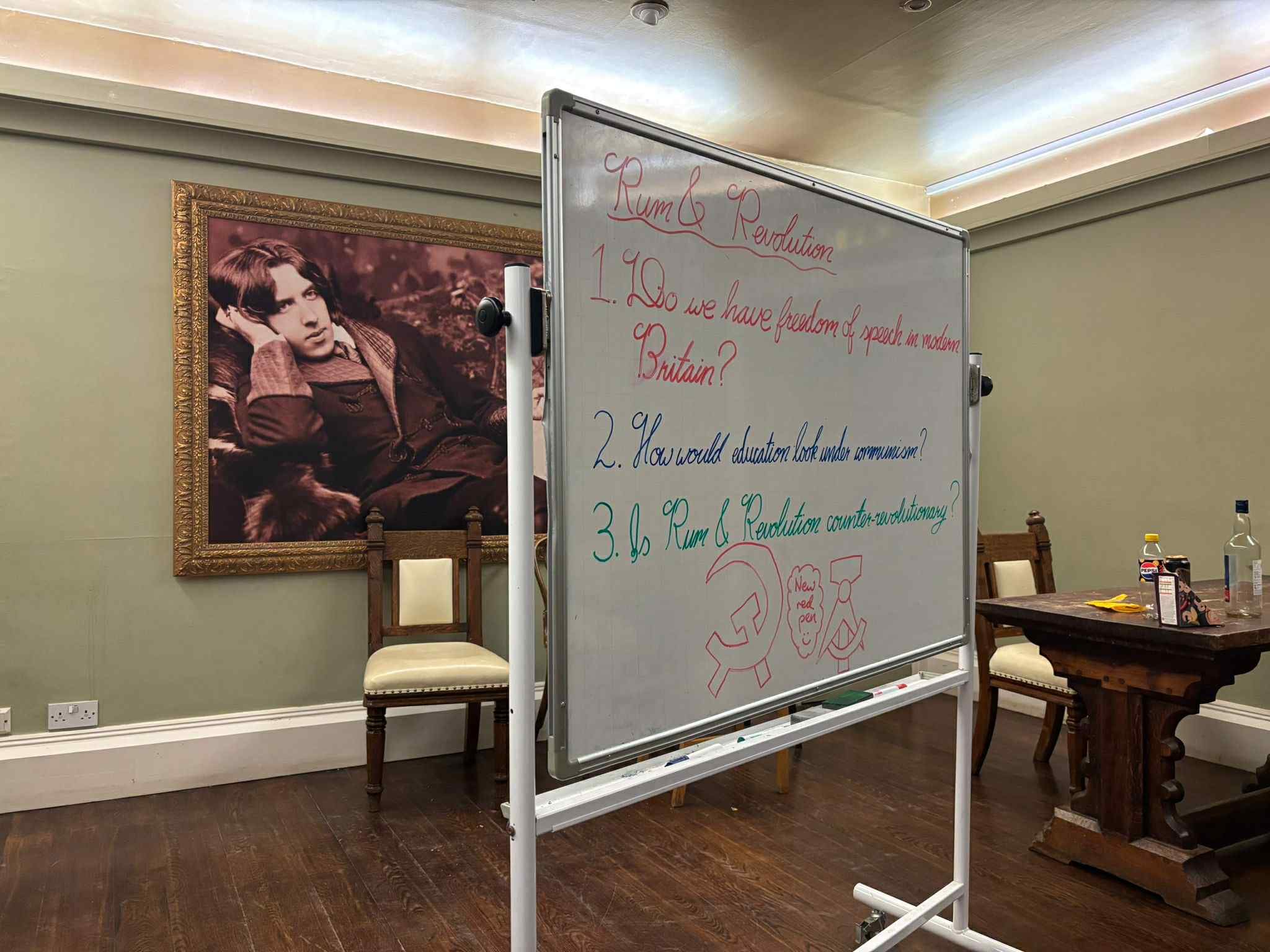

Rum and Revolution – The October Club

The following Friday I join my proletarian brothers (it’s all men) at a gathering of the communist October Club hosted in Magdalen, one of Oxford’s richest colleges. The stately Oscar Wilde Room is quite the contrast from the rundown scout hut where the Conservatives mustered. I’m handed a Guiness (I’m enjoying the communal spirit already) and we get cracking with the first motion: ‘do we have freedom of speech in modern Britain?’

The formula, in which we chat first in little ‘breakout groups’ before sharing our thoughts with everyone, works well. There’s none of the showmanship that comes with addressing a large crowd, so we’re actually able to have a normal conversation. We discuss incitement to violence, no-platforming on campuses, Kathleen Stock and the recent terror charges against a member of the Irish hip hop group Kneecap.

Image Credit: Stanley Smith (for Cherwell)

Next up, ‘what would education look like under communism?’. At this point, it quickly becomes clear that there are very few actual communists in attendance. In our group is myself, an OLC committee member, and several Australian post-grads with distinctly liberal politics. The one actual October Club regular gets us started by voicing his objection to the “authoritarian power of the teacher” and advocating for a decentralised, communal approach to education: although he declines to flesh out what this would actually look like. The conversation is quickly steered to more ‘realistic’ aims, such as reducing the cost of higher education. During the whole group discussion, the faces of the committee members become increasingly downcast as they realise they are playing host to what is essentially left-leaning liberal chit chat, rather than real talk of revolution.

This divide comes to the forefront with the self referential motion ‘is Rum and Revolution counter-revolutionary?’ The Aussies, pretty inebriated at this point, are full of praise for the evening: “this is what we need, coming together to find common ground!” The communists are unimpressed, pointing out that sitting around talking placates us from taking real action. We might have affirmed our lefty values, but will we take part in any protests? Will we go down to the pro-Palestine encampment set up in the Angel and Greyhound Meadow? The fact that the room is entirely white and entirely male is raised, something that everyone agrees is a problem, but no one is quite sure how to address. The evening ends with this tension unresolved.

Out of all the parties I visit, the society most anxious to stop talking and start doing, through its lack of careerism and its well-structured format, is actually the best conduit for a good discourse. Unfortunately for the organisers, the conversation doesn’t always go in the direction they would like.

Liquor and Liberalism – Oxford Students Liberal Association

The following Wednesday, I stand outside of the venue in New College. I pause before entering, mentally preparing for another evening of endlessly introducing myself. When I walk in, however, I realise I won’t have to. Inside is every white man from Port and Policy, and one or two from Beer and Bickering as well.

The setup is two long tables positioned so that, when we sit down, the sides are facing each other. This gives the room a distinctly House of Commons feel, a vibe that is bolstered by the conduct of the members. As the ‘speaker’ for the evening walks to the centre there are cheers, banging of tables, and shouts of ‘resign!’

The first motion? ‘This house believes that Britain was ‘“freest” between 1832 and 1918’. A person I recognise from OLC kicks off proceedings by pointing out the obvious: no, Britain wasn’t “freest” when women and working-class men couldn’t vote. “Point of information” interrupts the guy sitting next to them, with a big grin on his face. “Wouldn’t you say that everything was just so much better then?” Roars of laughter.

I realise now what I’m in for. Each speaker offers their own brand of edgy humour (Get the kids back in the mines! Rebuild the British Empire!) “It’s basically just a stand up comedy club,” the bloke I’m sitting next to takes it upon himself to explain. This isn’t eminently apparent to me as we endure a five minute speech given in all sincerity about how the decimation of the “British officer class” during World War I put Britain on a path of terminal decline. As for the ‘comedy’, many of the speakers don’t quite have the charisma to pull it off, nervously looking around the room and stumbling over their words as they quote a brain rot meme from TikTok.

During the second motion (‘this house would cut the foreign aid budget’), there are a few more serious speakers. An ex-president gives an impassioned defence of foreign aid, while a committee member rails against it as an enormous waste before she is informed that we have, in fact, already slashed our spending. One member goes on a jingoistic tirade declaring that bombs, not nappies and bandages, are the way to assert Britain’s power on the world stage. I’m sitting next to her, so I can see the faces of the guys opposite as they light up with admiration.

The evening continues in this manner, three silly speeches for every serious one. I feel increasingly awkward being there in my capacity ‘as a journalist’. This doesn’t feel like a public political meeting of people brought together by shared values, certainly not by a commitment to the Liberal Democrats. Instead, I’m observing the goings on of a small friend group which just so happens to revolve around the Oxford political scene. In the same way I wouldn’t sit on the sofa with a group of friends I don’t know and stick everything they say in Cherwell, my presence feels like an unwanted intrusion.

“Across the board, these gatherings are not even pretending to have carefully-considered solutions to the very serious public policy issues facing the British people.

Oxford politics: an increasing irrelevancy?

As with the national level, politics in Oxford seems more fixated with personality than party. Both Port and Policy and Liquor and Liberalism feel like another forum for aspiring BNOCs to mingle, rather than groupings with any sense of party identity. Beer and Bickering, on the other hand, seems to be suffering from the opposite problem. It’s so hamstrung by its commitment to the national party that it dares not voice alternatives to the policies of a government it’s clearly thoroughly disappointed in. Across the board, these gatherings are not even pretending to have carefully-considered solutions to the very serious public policy issues facing the British people.

So what about the alternative parties? If you’re looking for a good discussion, I’m tempted to recommend the October Club, but they’re not always so welcoming to those less enlightened than themselves. There are also clear gaps in the political landscape. Both of the insurgent parties, Greens and Reform, have next to no presence, although many members of OUCA expressed their belief that it won’t be long before a ‘Stella and Stop the Boats’ is created.

Ultimately, the innovation which will shape tomorrow’s politics isn’t happening in Oxford anymore. British politics is no longer dominated by the friendships made by undergrads ready to take the reigns of powerful party machines. What I witnessed was a small elite jostling for an inheritance that’s long been spent. Far more important in the politics of today are social media algorithms, fury at living standards that haven’t improved since 2008, and a popular hatred of politicians. Wherever the politics of the future is, it’s surely very far from here.

Editor’s note: An earlier version of this article, as well as the print edition, incorrectly claimed that there were eight male speakers in a row during Beer and Bickering, and referred to one of the speakers in Liquor and Liberalism as a man, who is in fact non-binary.