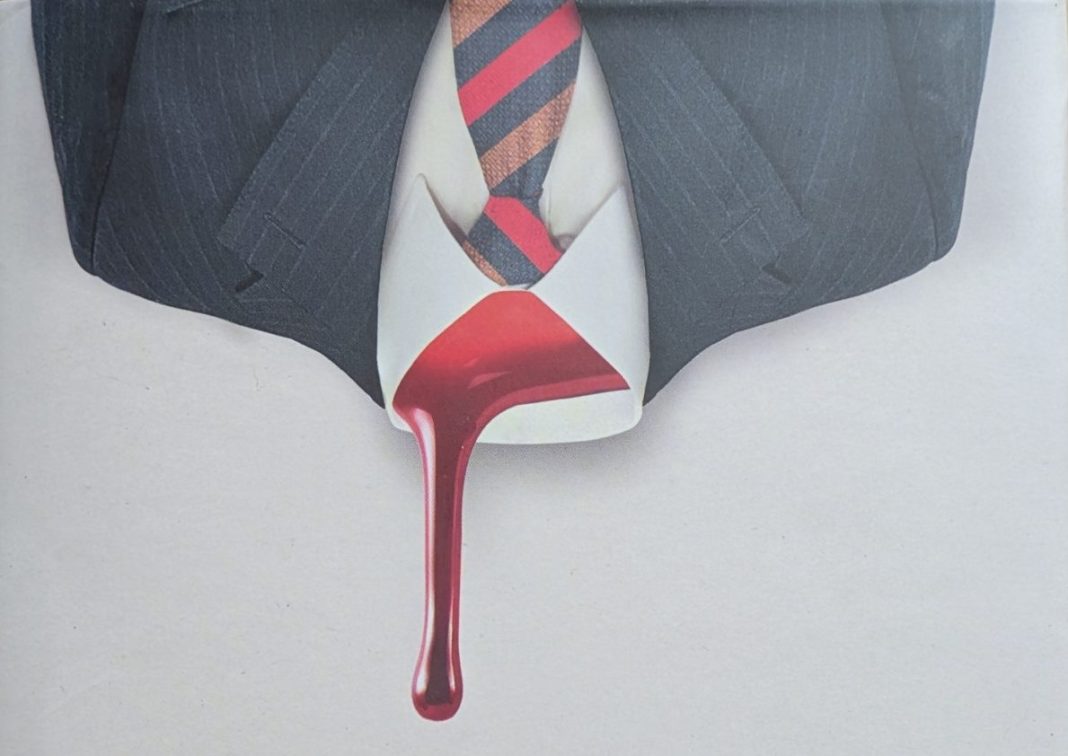

In the underbelly of Hong Kong, a Goldsmith-Sachs Vice President invites a woman back to his penthouse apartment for sex. Once there, he tortures her hideously for days, filming it for masturbatory purposes and eventually hiding his victim’s corpse on his balcony when she succumbs to her injuries. The opening section of The Wykehamist, poet Alexandra Strnad’s first novel, is a brutal introduction to a book filled with misogynistic violence, gluttony, and obsession.

Above all, Strnad is interested in privilege: Vice-President Lucian is a privately-educated (the title refers to alumni of Winchester College) Cambridge-graduate whose psychopathy has been facilitated by the ease with which people turn a blind eye to the actions of the beautiful and wealthy. Admittedly, when we meet him next in Hong Kong he’s less lucky, now in prison for the serial killings of a string of vulnerable women. It’s as his visitor that we’re introduced to Clementine, an accomplished journalist and fellow Cambridge alumni who has been obsessively stalking Lucian since he first walked by her outside Trinity College Library.

From there, the book flits between the past and present, detailing how Clementine began observing Lucian from afar, following him to an ill-fated Varsity trip, and eventually befriending his ‘gyp-mate’ (Strnad provides little explanation on the Oxbridge terms she uses; ‘gyps’ are small kitchens shared by stairways in Cambridge colleges) in order to gain access to him. Lucian, meanwhile, attends dinners at the prestigious Pitt Club, flirts with various elite women, remains completely uninterested in Clementine, and eventually begins an exploitative relationship with a homeless girl named Kimberley, satisfied that the wealth disparity between the two will maintain a power dynamic in his favour.

Strnad herself studied English at Cambridge, as Clementine does, but ironically it’s the passages set outside the town – in London and Hong Kong – which are the best-written. It’s here Strnad displays her talent for carefully toeing the line between repellent and arresting, in describing Lucian’s spiralling, gluttonous search for power, food, and women. That said, The Wykehamist is by no means a comfortable read, but Strnad knows how to use the viscerally disgusting to prevent any romanticisation of the killer in this true crime tale.

This is also what makes Clementine’s obsession with Lucian so incomprehensible to the reader. Granted, she has no comparable insight into his psychopathy, but he is an open chauvinist who treats her with contempt the few times they interact, and almost forces her without warning into a threesome with Kimberley. The Wykehamist’s interest in power naturally extends in passages like this to an examination of misogyny, of which there is plenty from both Clementine and Lucian. In fact, most of the women (with the exemption of Kimberley and the sex workers in Hong Kong) are seemingly willing participants in their own maltreatment. Clementine explicitly says she abhors feminism, and near the end of the novel – despite nearly seven years on from her last meeting with Lucian – pays for Tiny, a sex worker from Jakarta currently employed by him, to fly home to her family not out of fellow-feeling but as a vindictive attempt to gain Lucian’s attention.

This in itself is an interesting commentary on the way in which privileged women can perpetuate sexist systems. But it is hard for us to understand what Strnad believes lies at the root of this phenomenon. And equally difficult to understand why Clementine’s unrequited obsession with Lucian forms and continues with such unchanging force, beyond the suggestion that they are both disdainful and aloof. Especially given that Strnad only dedicates a page to its development: by the end of the passage, we are told, rather than convinced, that she was fixated on him, and she remains so throughout the book with hardly any sense of crisis or emotional development. Likewise, we lack any emotional insight into Lucian, and when hints are given they are asserted, rather than implied. We are told he feels shame for his disabled father, but it is dwelt on briefly, and no alternate motivation for his violence is offered. The emotional stagnancy of the characters may be a commentary on the untouchability of the privileged, and the innate perversity of the psychopathic, but it still left me unsatisfied.

The blurb describes the book as a cross between American Psycho and Saltburn, and the similarities to the latter are clear. Both Clementine and Oliver, Barry Keoghan’s character in the film, become obsessed with an upper-class classmate, and both pieces of media lay bare the operations of privilege. For Strnad, the way in which the rich stay rich through the Oxbridge-only circles of commercial London; for Fennell, the hereditary house-ownership and ignorance which underpins undue advantage.

But just as Saltburn’s attempt at social commentary fell flat, The Wykehamist does a better job at exemplifying entitlement than interrogating it. Clementine is not privately educated, and her insecurity over this seems to fuel the way in which she colludes with Lucian’s misogyny in antifeminist rants against her fellow female actors. But her complicity with Lucian robs the novel of the opportunity to critique the systems it lays out: like Oliver in Saltburn, Clementine really just wants a cut of the system, rather than its take-down. The only working class individual, Kimberly, is attacked by Lucian, leaves, and is announced by the narrator as gone for good. You mourn her loss, not only as the only semi-likeable character, but as one who provided a crucial alternative perspective in the tale. The potential message of the novel, it seems at first, is ‘privilege dulls empathy to the point of psychopathy’, but when Lucian asks Clementine at its end whether she thinks it was Cambridge that ‘did it’, she replies no. By providing us little insight into Lucian’s background, childhood or private education (bar some very interesting passages right at the end), Strnad dulls this critical potential with the suggestion that he is just intrinsically misogynistic, obsessive and manipulative. Some people are just born bad, she seems to be saying.

Strnad is certainly a talented poet, and The Wykehamist indicates she has great potential as a novelist. But it is ultimately, like Saltburn, unimpactful. Clementine reflects in the last line that she was the ‘winner in this game’, but the reader cannot share in her confidence for The Wykehamist seems unresolved both as to what that game is, and whether the central players even stand on opposing sides.