Hogwarts students run up the Christ Church stairs. Saltburn’s stars roll cigarettes on a Brasenose College quad. And My Oxford Year’s Anna and Jamie wander up to Duke Humphrey’s Library.

Walking through Oxford, you’d be forgiven for thinking there are two levels of reality. First, the actual, which involves hungover tutorials, looming deadlines, and endless crowds on Cornmarket. Sometimes more prominent is the artificial: an Oxford that is romantic, fantastical, and immaculately lit.

There are two main ways the city is shown on screen: sometimes as a fantasy backdrop for an unrelated story, and sometimes as itself, in a tale recreating the minutiae of the University. Such presentations raise Oxford’s profile, draw visitors to the city, and cut off streets for film crews. When the endeavour disrupts learning and risks misrepresenting Oxford, the question arises – is all this filming a good thing?

A magical city

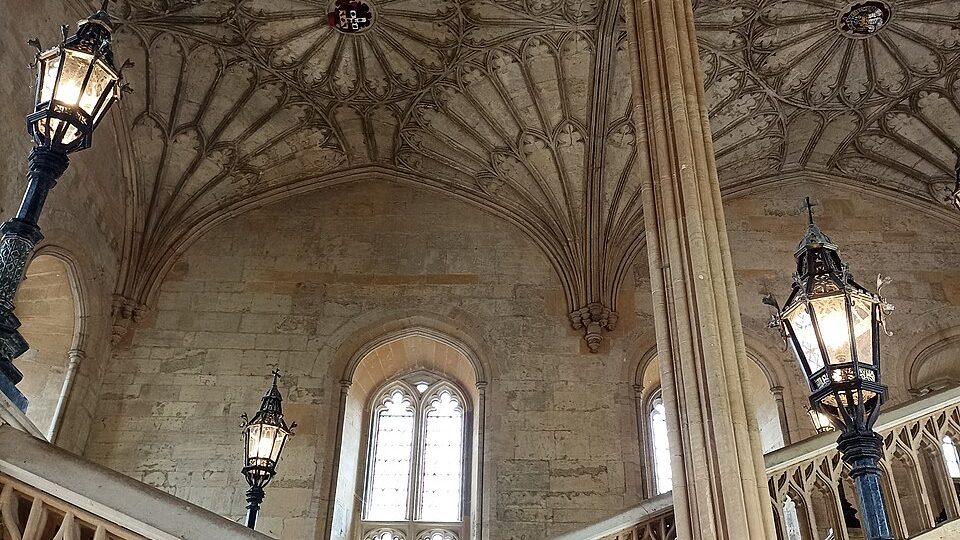

Oxford’s turn in the Harry Potter franchise has proved one of its most profitable modern features. Hogwarts fans swarm well-known filming sites across colleges, while, on GetYourGuide Harry Potter walks are the main filter option for the city, out-ranking Tolkien, Morse, and the University itself. It’s a strong example of Oxford when filmed in the fantasy genre – sweeping staircases and vaulted ceilings create an arcane, mysterious environment, so alluring it takes on its own character.

Tourists drawn to this version of Oxford appear to view it as their own theme park, replete with backdrops for social media. A Christ Church student told Cherwell that they see “more adults than children” on the College’s busy staircase. Along with Cornmarket Street’s dense concentration of shops selling swords, wands, and University hoodies, they speak to a nostalgic desire to be physically transported to another world.

Other fantastical media, inspired by Oxford but not filmed there, fails to capture the public in the same way. Alice in Wonderland was written by a former Christ Church student, Lewis Carroll, partly influenced by Oxford’s locations, people, and history. It, too, takes place in an otherworldly, exaggerated dreamland, and is, like Harry Potter, a staple of children’s literature. Yet, in the city that helped create the story, tourists don Hogwarts robes, rather than Cheshire Cat ears.

Both franchises draw their popularity from escaping the modern world, but only one provides photo opportunities. A tour guide can point out long-necked brass andirons that may have inspired part of Carroll’s story, but there are no parts of the novel that a tourist can ‘enter’. The ‘real’ Hogwarts, however, is endlessly accessible. While this may explain the sea of dark academia edits set to Lana Del Rey’s ‘Say Yes to Heaven’, this is not the reality of life in Oxford. Fantasy may sell, but it misrepresents the mundane staples of most actual students: Tesco Express, bad signal, and Bridge Thursday.

Oxford as usual?

Other films are set in the ‘actual’ Oxford, but include just as much fiction as fantasy does. Netflix’s My Oxford Year (2025) was a particular target for students for inaccuracies. Based on the novel by Julia Whelan, the film portrays a student enamoured by ‘The Oxford Aesthetic’, until reality takes over. The film’s prominence has caused a surge of Oxford students posting on TikTok about their experiences watching it. Creators participate in “tak[ing] a drink every time they get something wrong about our uni challenge”, and “trying to watch without complaining at every single inaccuracy”.

Cherwell spoke to the author about these inconsistencies. Whelan, who herself studied at Lincoln College in 2006, was initially “inclined to see the negative” of Oxford’s portrayal in films.

“Books seem to get [capturing Oxford] more right, more often, than film, I think. It’s what I attempted to do in writing My Oxford Year. A very gratifying outcome has been the outreach of many Oxonians who read the book and then let me know it captured the essence of the place, that they felt an authentic melancholic nostalgia while reading. This response was such an unexpected boon, because my initial goal was to make people who hadn’t gone to Oxford feel welcome.”

Since her time at Oxford, she’s changed her perspective on its on-screen portrayals: “The thing I’ve come to accept about media is that it meets people where they are, and you can’t control where that is. Some will only connect on one level (it was so funny/so sad/so romantic!) and others will find complexity and depth where you maybe never even intended it. I don’t think one should set out to “romanticize” (or put another way, flatten it into one dimensionality), but I would push back a little at any implication that all stories must grapple with all sides of a certain thing lest people get the wrong idea about that thing.”

Despite this consideration, Oxford on film seems firmly situated in past incarnations of the University, particularly in Emerald Fennell’s Saltburn (2023). Fennell depicts an anglophilic Oxford defined by aristocratically chic students, high-class debauchery, and costume parties featuring Sophie Ellis-Bextor. The story is set in the early 2000s, but the classism from the characters is positively Victorian – poorer students are intimidated into buying rounds of drinks, and regional accents are relentlessly mocked. Filmed in Brasenose, a college with almost 80% state school students and a strong tradition of outreach to Yorkshire, the representation of Oxford in Saltburn risks preserving stereotypes and undermining the work done by the University to improve access and outreach.

It should be said that while these stereotypes are considered inaccurate and antiquated by many, there is some truth to these cinematic versions. Students remain attached to Oxford’s mysticisms – a 2015 referendum voted to keep sub fusc for exams, over 6,400 wishing to continue the tradition. As for the reality of Oxford’s diversity, not only did 2024 see the lowest intake of state school students since 2019, but applications from international students to UK universities have also decreased by 6.75% between 2022 and 2024 – the first and biggest fall since 2012/13.

Cameras on the quad… and in the library

Conflict between Oxford on screen and Oxford in reality can also be more literal, when filming encroaches on everyday college life. Tensions between students and film crews arose recently after Brasenose College closed its library to accommodate shooting for the forthcoming sequel to My Fault: London. Two quads and the dining hall were overrun by cameras and extras. Disruption clashed with exam season (taking place over 9th week, Trinity term), and prompted questions surrounding the priorities of the College. The Bursar told Cherwell they had “underestimated the impact of filming” in their impact assessment, and apologised to the students affected.

Colleges commit to accommodating students, academics, and film crews. And camera crews are certainly not absorbing the downsides of this arrangement. Lex Donovan, location manager for Netflix’s My Oxford Year, described working at Magdalen as “very smooth. We shot during the holidays, so fewer students were around”.

Even after the camera crews have left, disruption continues, as fans flock to filming locations. A Christ Church student told Cherwell: “I was nearly late for my Dean’s Collections because I hadn’t factored in weaving through the tourists”, and that, once, a tourist berated his friend “for walking in front of his photo” while on the way to a class.

So, what makes colleges open their doors to film crews?

The undoubted publicity of a blockbuster filmed on your front lawn is enticing. Oxford’s 2024 UK admissions statistics somewhat reflect this. Magdalen, where My Oxford Year and much of Saltburn was filmed, received 2,503 applicants, more than double the number received by St Hilda’s, who have not appeared in any recent, well-known media. New College, Brasenose, and Christ Church also dominated domestic applications.

Yet Worcester College was on top with 2,623 domestic applications, despite lacking specific media fame. Balliol also made the top five, despite their relative cinematic insignificance.

Regardless of whether franchises call them home, the most popular colleges all fit into the idea of the Oxford experience perpetuated by so much of the media filmed in the city. The expectation of palatial gardens and towering spires diminishes the ‘Oxford-ness’ of smaller, more modern colleges like St Peter’s and St Anne’s, which were much lower in the application rankings. The presentation of Oxford onscreen as 100% yellow brick risks narrowing horizons of prospective applicants, and reifying the city as fantastical yet inaccessible.

Beyond cultural capital, the University’s financial motivation for such attention is still unknown. A Freedom of Information Request from Cherwell to Brasenose revealed an annual filming income of £6,170 for 2024, and £43,827 for 2023 (the College declined to share data for the financial year ending in 2025, citing commercial interests). In terms of income, endowments (£644,000), tuition & research (£3.3m), and residential (£4.5m) provided far more to the College in 2024. The tuition fees of just one domestic undergraduate student are 1.5 times the profits from all filming at Brasenose in the same year.

According to Oxford City Council, the city receives around seven million visitors annually, which generates approximately £780 million per year. Planning for an Oxford ‘tourist tax’ of £2 for overnight visitors seems to be a less-disruptive, passive profit method, as does the £5 congestion charge recently authorised by Oxford City Council, placing a toll on every vehicle passing through certain zones of the city. Still, it is unclear if this income and subsequent cultural relevance outweigh the disruption media production causes to daily student life. Is this side hustle really worth the hassle?

“Trapped in amber”

Oxford has been immortalised from a hundred different angles, yet, as a student, watching the city onscreen provokes a disconnect. Part of this is simply time. Whelan, whose year at Lincoln was 2006, felt that she would be ill-equipped to write about Oxford in 2025, worrying My Oxford Year “will feel trapped in amber sooner rather than later… I thought I’d have a bit more time before someone would look at my character’s Oxford experience the way I looked at Sebastian Flyte’s, but here we are. The future comes for even the most timeless of cities.”

It takes years for someone’s experience of Oxford to make it to the screen, and by that time, the city has moved on. The film-inspired underlay will lag a few years behind, while the enchantment that current students find is ever-changing. These stories try to capture the real magic of the city, whether in the robes of Harry Potter imitating sub fusc, or the streetlamp in Narnia reflecting Radcliffe Square. But they are echoes of actual experiences, animated by other students – walking to Exam Schools with the rest of your subject for prelims, stumbling back from clubs down centuries-old streets, wearing a ballgown on the same quad over which you carry your laundry. They’re the kind of things that can’t be found on a walking tour.

What remains certain is Oxford’s duality, as a city of both students and screenings. Its popularity is built on nearly 1000 years of stories, fantastical and otherwise, from the people within Oxford and the University. Using the city as set dressing raises funds and college profiles, but also disrupts actual student life, and risks reducing Oxford to a set of stereotypes. Perhaps it is no surprise that the foundation of Oxford, its students, now wish to be the ones calling “CUT!”.

Image Credit: Daniel Norton CC BY-SA 4.0 via

Wikimedia Commons.