The waiter has just brought the bill, irritatingly diplomatic in his placement – middle of the table. You both glance at it, then at each other, caught in that peculiar modern standoff where nobody’s quite sure what the right move is any more. Will they think I’m old-fashioned and patronising if I offer to pay? Rude if I suggest splitting it? All the while, the nagging question lingers of whether the gesture means anything if it comes out of daddy’s Barclays Premier Current Account. So, has chivalry had its day? Or does it just look different in 2025 – a world of situationships and automatic doors?

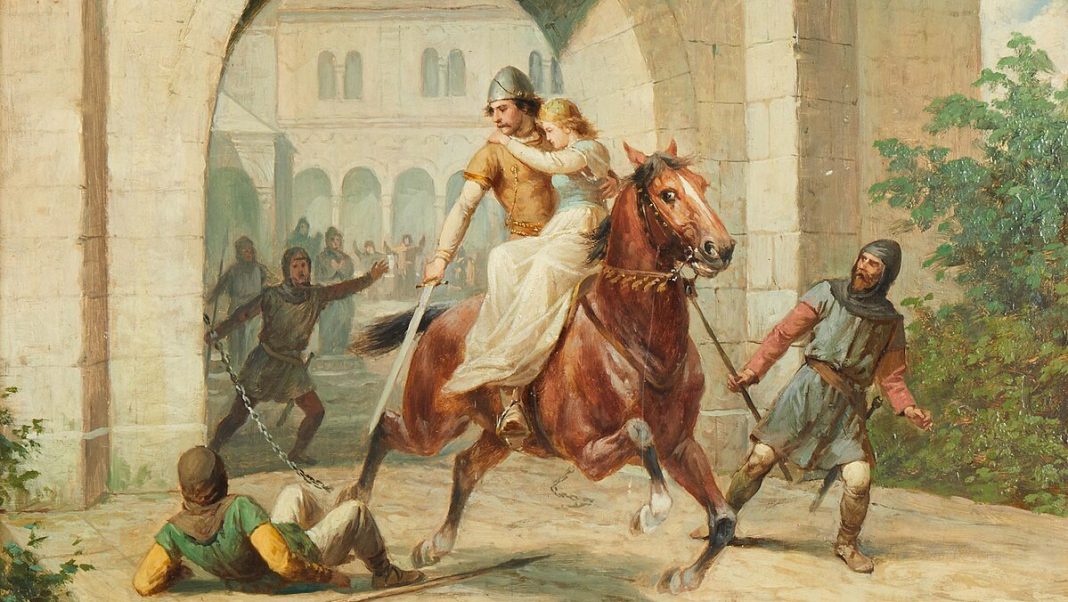

Believed to have been coined in medieval England, stemming from the French ‘chevalerie’, the term originally referred to horse-mounted soldiers, but later became associated with the behavioural code that these knights were expected to follow. A code that encompassed loyalty, honour, and courtesy.

Taking this as the definition, I don’t think chivalry is dead, nor does it need to be. What I do think is that we’ve been approaching it all wrong. The problem isn’t that men do or don’t open doors for women, or offer to pay for dinner. The problem is that we’ve made chivalry about gender rather than kindness, about grand gestures rather than basic human decency.

True chivalry, surely, is about extending courtesy to anyone who might need it, regardless of their sex. It’s about recognising that a fellow human being is struggling with a heavy bag outside Blackwell’s and offering to help. It’s about saving someone’s seat in the Bodleian when they’ve gone to find a book. It’s about sharing your lecture notes with the person who was too ill to attend. These don’t need to be patronising acts, but simple human kindnesses that make daily life a little more bearable. Modern chivalry doesn’t need to be limited to the acts of males towards females.

Besides, modern dating practices can be more than a little confusing. How do you navigate traditional gestures of courtesy when you’ve both agreed that your relationship exists in some undefined space between friendship and romance? Does offering to pay for a meal signal an inappropriate investment in a situationship?

The truth is that some people genuinely don’t want doors held for them, meals paid for, or heavy bags carried. And that’s absolutely fine. Part of modern chivalry can be reading social cues and respecting boundaries of individuals. The key is making the offer without expecting gratitude, and accepting refusal without taking offence.

The academic pressures of Oxford life certainly don’t help. With everyone desperately clawing to stay afloat, with the weight of 900 years of academic tradition resting on our shoulders, basic consideration for others can sometimes become lost in it all. We’re so focused on our own deadlines that it can be difficult to notice the opportunities to help someone out.

The cruel irony is that this may be exactly why we need it most. In a world where we’re increasingly isolated by our phones, carefully curated social media presences, and never-ending coursework, small acts of human consideration become more valuable. A form of chivalry that has nothing to do with horse-mounted knights and everything to do with simply paying attention to the people around us.

Infrastructure can also get in the way. Every term seems to bring a fresh batch of automatic doors, rendering a door-holder-opener entirely obsolete. I have nothing against automatic doors, but there’s something vaguely melancholic about watching a steady stream of students flow through the Schwarzman Centre entrance without so much as a second of eye contact, let alone holding anything open for anyone.

I am all for a man acting courteously towards a woman – in the same way that I am all for a person acting courteously towards another person. I would hope that these acts of ‘chivalry’ are not carried out on the patronising condition that the recipient is female. So no, chivalry isn’t dead; it’s just evolved. Modern courtesy isn’t about men protecting women because they need protecting. It’s about human beings looking out for one another where we can, acknowledging our shared vulnerability and, occasionally, dependence. It’s about being the sort of person who makes other people’s lives fractionally easier, not because you want anything in return, but because kindness, as it turns out, is still worth practising. But as for restaurant bills: God knows.