The UK confirmed on the 1st May that it had detained an unspecified number of asylum seekers in the previous few days ready for deportation to Rwanda in July. This comes after legislation passed in Parliament that same week in support of such an arrangement, which would see forced deportations of asylum seekers to have their claims processed abroad. A man has reportedly already gone voluntarily to Rwanda. The policy purports to primarily focus on those who have taken a dinghy to cross the English Channel. According to the BBC, there are currently 52,000 people in this pool. Rwanda has “in principle” agreed to accept 5,700 migrants already in the UK this year.

Filippo Grandi, the UN High Commissioner for Refugees, has said that the UK’s Safety of Rwanda (Asylum and Immigration) Bill is “setting a worrying global precedent.” One may wonder, then, whether the UK is the first to have innovated such a policy, and whether other countries will follow suit – as hinted at by the UN.

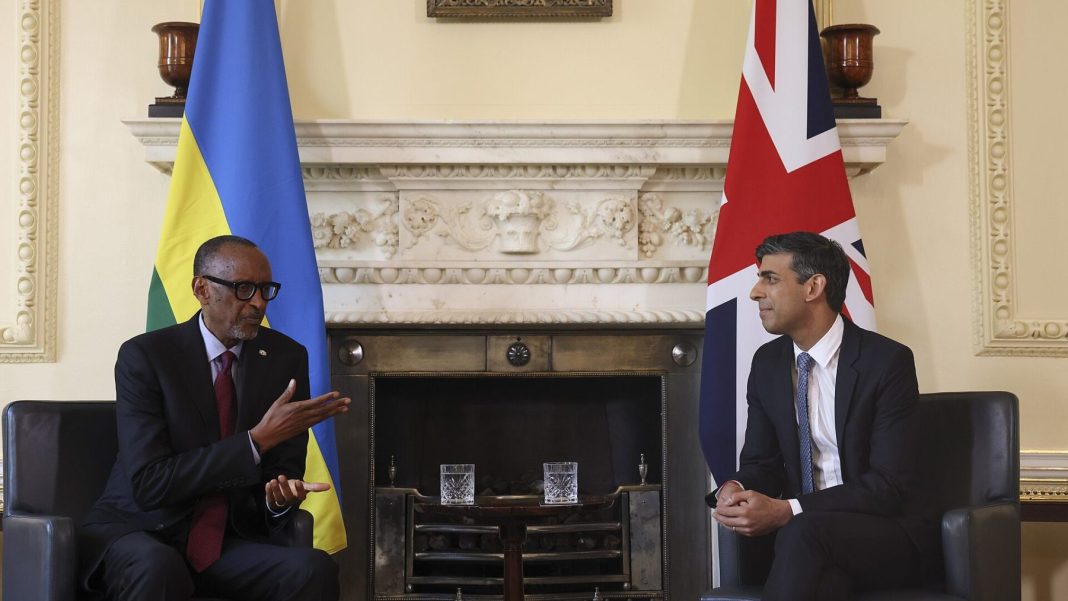

Firstly, the policy was ruled as unlawful by the UK Supreme Court, citing concerns that Rwanda could not be considered a safe country. Rishi Sunak subsequently circumvented this by drafting the now successful bill which legislated for the designation of Rwanda as a safe country.

As the UK’s Refugee Council has expressed, the concern with the Rwanda deal may not just be about Rwanda as a destination. It is concerning that a country like the UK, which does not take a very large share of the proportion of the world’s refugees, still considers it necessary to transfer them abroad. The UK is capable of finding other ways to promote safe routes to its country, and it can find the resources to process the claims it receives domestically.

Australia introduced a deportation policy in 2001, similar to the UK’s current policy, targeting migrants arriving in Australian waters by boat. Asylum seekers were transferred to offshore detention centers in Papua New Guinea’s Manus Island and the South Pacific island nation of Nauru. The policy went through several changes, including a brief dismantling between 2008 and 2012. It was only last year that the last few asylum seekers pursuing Australia as a destination were relocated from Nauru. The policy had a reputation of being extremely costly for Australia and one may wonder, given the UK is also facing financial pressures if the Rwanda agreement is implemented, whether the UK will sustain the policy longer, or even as long as Australia.

Additionally, the BBC reports that some 4,000 Eritrean and Sudanese asylum seekers based in Israel were sent to Rwanda and Uganda between 2013 and 2018. Other reports suggest they were given the choice of either being deported to their country of origin or accepting a payment of $3,500 and a plane ticket to either Uganda or Rwanda, facing jail in Israel otherwise. However, the agreement between the countries was secretive and eventually abandoned. Nonetheless, given the Australia model has already inspired the UK, and similar legislation in Denmark which was not implemented, it may be expected that other countries will also find inspiration in the formalised Rwanda deportation model.

But which countries may follow suit? According to the Spectator, “asked if they would like France to adopt a Rwanda-style bill, 67 per cent of the French canvassed replied favourably to the idea.” Although current French leadership remains opposed to the idea, any possible future change in leadership, especially a change towards a populist one, may lead to a French Rwanda-style deal. It is worth noting that French support is higher than the 37% that view the policy favourably in the UK, according to a YouGov poll in January.

Arab Gulf States have also conducted weekly deportations of migrants, facing huge criticism. Given they are claiming to be working to improve their human rights records, they may see the UK-Rwanda model as one that they could follow. ُThough they are not signatory to the same international agreements, the UK is a country that publishes Human Rights and Democracy Reports as part of the Foreign, Commonwealth & Development Office (FCDO)’s efforts to promote human rights abroad. If the UK is seen going through with such policies, then that may hold its weight in policy considerations of other countries – especially as they may view the UK as a global leader or have strong historic ties.

Yet such a consideration may be misleading. Although the UK is indeed a country that holds its weight internationally, including as a member of the G7 group of advanced democracies, it is not immune to making mistakes on advancing and protecting human rights. This may be the UK’s contemporary moment of violating such rights. Therefore, it is certainly not a good idea for other countries to follow suit, even if they will naturally watch closely to see the legal and reputational backlash the UK may receive. If the UK survives this backlash, it may inspire them. However, this inspiration would stand in the way of better solutions that could be developed to migration issues.

Lastly, even if other countries do not follow suit, the UK itself may expand the policy to deport asylum seekers to other partners. Reports have indicated Armenia, Ivory Coast, Costa Rica, and Botswana as contenders for similar arrangements with the UK. This is possible not only as Rwanda has limited capacity, but also because Rwanda may be risking domestic political trouble by receiving all these asylum seekers. In fact, though much of the blame for this policy is rightly set on the UK, Rwanda should also bear some of the criticisms that arise from this deal. Many countries have reportedly declined being approached by the UK for a similar deal, including Morocco and Tunisia. Rwanda still has the chance to be the last line of defence against this policy, preventing the proliferation of a costly, abusive, and populist solution to international migration.