Real tennis? What, as opposed to fake tennis? No, real as in Real Madrid, as in royal. That’s perhaps not the best way to describe it, but it’s somewhere to begin explaining what Oxford’s real tennis club – or rather, tennis club – is all about. On a Thursday afternoon, professionals Craig Greenhalgh and Nick Jamieson are restitching a batch of real tennis balls by hand when I visit: unlike the fuzzy lawn tennis balls you’re probably more used to, real tennis balls are heavier, entirely handmade, and their skins have to be replaced every two to three weeks. I’m supposed to watch their practice session, but I’m early and the group before are still going at it. “There’s a couple of 90 year olds on there right now”, Greenhalgh says.

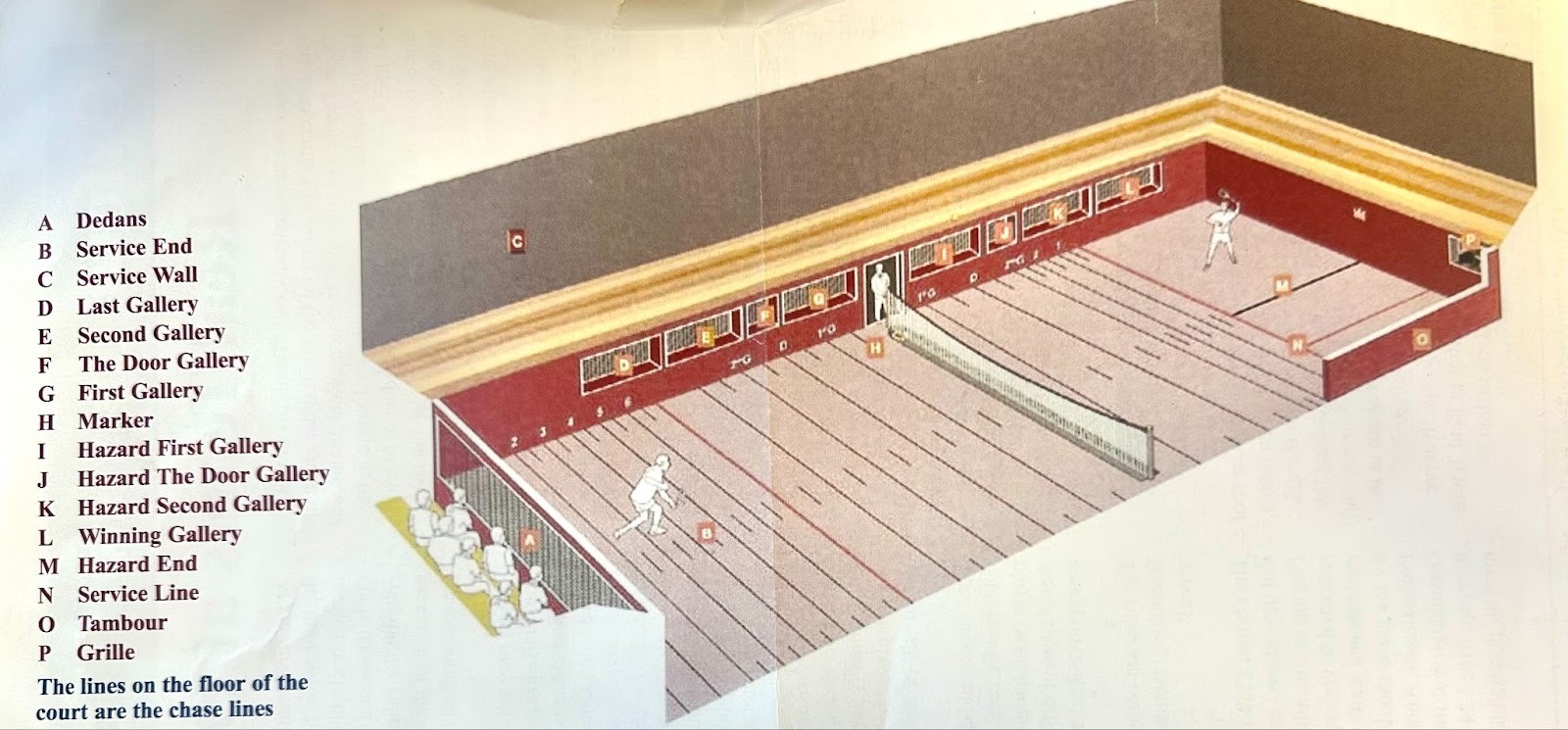

This sounds quite frankly implausible to me: I don’t think I’ve ever seen a 90-year-old do a sport that isn’t tai chi. Jamieson pauses his work to take me through the clubhouse into the court itself so I can witness it with my own two eyes, but what we enter isn’t anything at all like what I expect. Imagine, if you will, a much smaller and completely enclosed indoor tennis court done up in the new colours of Balliol bar. Imagine that at one end of the court, at Player A’s back, there’s netting instead of a wall, behind which there’s a little seating gallery for spectators. Now imagine that, on that court, there are four men with completely white hair having a genuine go at this game. “Nasty serve, Nigel”, Jamieson calls, and one of them chuckles in acknowledgement.

Veiled by netting – which I learn is called the dedans – I still flinch when a ball comes arcing toward us; unbothered, Jamieson gets up to prepare for his session. “Tea?” he offers.

Plenty of sports today – tennis (real or otherwise), fives, handball, squash – owe their origins to jeu de paume. Literally translating to “palm game”, it was a game played in France in monastery cloisters around the twelfth century that involved hitting the ball with – you guessed it – your palm. Made popular in England by its monarchs, by the 1500s real tennis had evolved into its modern form: rackets, convoluted rulesets, and all.

Built in 1798, the court in Oxford is the second oldest in the country, behind only the one in Hampton Court Palace, where Henry VIII played. To my surprise, it’s also one of the busiest in the world: “We’re booked out 7.30am to 10.30pm, every day of every week,” Greenhalgh says.

Historically both elusive and exclusive, real tennis precedes what we think of as tennis by about three hundred years. Mostly the domain of nobility, it started falling out of favour compared to lawn tennis in the 1800s because of its difficulty and inaccessibility: there are now only 45 real tennis courts in the world, as compared to 3,000 lawn tennis courts in London alone. Oxford itself used to be a veritable hub of real tennis: “In the 1450s, colleges used their real tennis courts as a way of attracting people to apply,” Sir Neil Mortensen, fellow of Green Templeton and President of the Club, tells me. According to Greenhalgh and Jamieson, one of Oriel College’s buildings even used to be a real tennis court: “I’ve never been inside, but it’s the windows at the top that give it away.” They are, of course, correct. Oriel’s Harris Building, now used for accommodation, was once home to the Oriel Square tennis court where Charles I played.

With most courts in the UK located near London, how players across the country get their start is a matter of pure chance. Greenhalgh fell into it 20-odd years ago in Manchester, after a friend of his father’s let him have a go; Jamieson found it after watching videos of the sport online. The club is unlike others at Oxford in that the majority of the members are non-students: 150 senior members, like the nonagenarians I saw, make up most of the club’s activity. One of them helpfully points out his own name – “P. Hartmann” – under the 1966 runner-up column of the Grant Bates Trophy, a club-wide handicap competition. “I’ve been playing here since the 80s”, he tells me in a hoarse voice.

For students, access to the sport is often gated by wealth. Rackets, an equally absurd game that precedes squash and fosters a skillset that translates well to real tennis, is ubiquitous at Eton, Harrow, and St Paul’s, among other offenders. “Last year, all of our first team were from the top public schools”, Leon Kashdan-Brown, a third year at Magdalen College and the men’s Blues captain, reflects wryly. “Three Etonians. Wasn’t any better with the second team – it was one person from Eton, and another from Winchester.” We collectively wince in sympathy.

But the lingering miasma of elitism is slowly fading. The men’s team this year doesn’t have a single player from a public school; Kashdan-Brown himself is the first state-school men’s captain in recent memory. “All except one of my players have never touched real tennis before”, Hannah Wilson-Kemsley, a fourth-year at Exeter College and the women’s Blues captain, tells me. Those who come to the club with a background in different racket sports – most commonly lawn tennis or squash – tend to find making Blues an easier process, but the majority of student members just want to try something new and interesting. There is some truth to the stereotype of real tennis as the realm of posh old boys, Wilson-Kemsley admits, but in this day and age, the playing community is so small that any airs of snobbery have essentially evaporated. “It honestly feels like there’s a genuine desire to get more people involved. The club is happy to have anyone – anyone at all – playing the game.”

And as for BUCS? “Well, only three unis have real tennis teams, so we don’t do that”, Kashdan-Brown says, laughing. (For those wondering: it’s Oxford, Cambridge, and Middlesex University, a public research university and former polytechnic.) Instead, there’s just Varsity, and the odd weekend trip to Abingdon or Reading for a friendly match, which makes for a much more relaxed and friendly atmosphere overall – or, for Wilson-Kemsley, in comparison to OULTC, which she also captains. The best thing about it, really, is that the professionals are always on hand at the club.

“Now that I’m here, you’re being nice”, Jamieson says archly, appearing at the door to the viewing gallery. “It’s true”, Kashdan-Brown protests. “Other clubs aren’t going to have external professionals around all the time.” By virtue of the handicap system, there’s also a great deal more chances to play with people far more skilled and willing to dish out advice: when you book court time, you’re just as likely to play a fellow student as you are a senior member or a professor at the University.

“Have you got those on hand for table tennis?” Jamieson asks. (Kashdan-Brown is also president of the university’s table tennis club, which puts my count of racket sports he’s playing at about four hundred.)

“You’re looking at one”, Kashdan-Brown says, dry.

The game itself is deeply complicated, mystifyingly opaque, and still, somehow, charming. Among the many archaic rules include one where if one of the players hits the ball directly into a certain gallery, they win the point straightaway – and it’s compulsory for every court to have a bell strung up in that winning gallery, so that the echo of your victory rings through the whole building.

A sound like cracking stone interrupts the captains’ attempt to explain even more rules. Through the netting, Greenhalgh smashes the ball straight at the wall opposite; its fall is slowed by the sloping penthouse, and by the time it hits the floor it’s lost most of its momentum entirely. Jamieson steps light and fast across the court, digs it out of the corner with a clean, sharp flick – like scooping something out of the air, almost – and sends it back in a high arc, as if no force’s been put on it at all. It’s quite obviously the father of squash and tennis, but really it reminds me more of badminton: the long-necked, slender racket, the speed at which the ball ricochets off the walls, the emphasis on footwork and technique. “I always say it’s like cricket, actually,” Greenhalgh tells me between sets.

The combination of rules and the small size of the court allow for points to be won in a manner that isn’t determined by athleticism alone, and by extension for a player lifespan that’s unthinkable in most other sports. The average age of a professional real tennis player is 37; Robert Fahey, the ex-World Champion, had a stranglehold on the title for 20 years before he finally lost it at age 50. It’s these older players – often incredibly wealthy – that keep the club afloat: senior members pay £325 for annual membership, most of which goes towards offsetting the £25,000 it takes to subsidise equipment for students, who pay only £80 a year.

Finances are further pressured by the costs of maintenance. The club’s building is property of Merton College, which demands that they repaint the facade every five years. “Last time, it set us back £20,000”, Mortensen says. It doesn’t help that they receive no funding from the university’s Sport Federation. “I suppose they see real tennis as a niche, non-generalisable thing and therefore not worthy of support.”

And after? After Oxford, with its cocoon of septuagenarian support and resistance to change? Back home, the nearest court to Wilson-Kemsley is an hour away by car; for Kashdan-Brown, in London, it’s Middlesex or nothing: “I don’t think I’m going to be in a position to play at Hampton Court, Queen’s, or Lord’s.” There’s a gulf of middle-aged players – “I don’t think I’ve ever played a senior member under the age of 40”, Wilson-Kemsley says – and for good reason: once you age out of full-time education, it’s nowhere near as accessible to keep playing real tennis. (At Hampton Court, annual membership for 25-29 year olds costs £352.)

“There was a bit of an existential moment after COVID, about whether or not real tennis was still something people wanted to play”, Mortensen reflects. “But it’s coming back now, really.” When I ask Kashdan-Brown whether he agrees with that assessment, he tempers his own optimism: “What I’m seeing, on my end, is this flow of students coming in and out.” From the outside, things look grimmer: the court in Middlesex faced closure in 2022, citing “limited impact on students”.

“It’s not like padel.” On this, at least, Mortensen and Kashdan-Brown agree. Real tennis is never going to be a growing sport; it’s an ancient one kept alive by the efforts of a dedicated, unexpectedly lively community. So, in a Schrödinger-esque dilemma: taking off or dying out? As long as you keep walking down Merton Street—who can say, really?