Pour out a glass for the second annual Intoxtigation. 562 respondents told Cherwell all about where, when, why, and how much Oxford students are drinking. Now it’s time to reveal the results. The best bar, the best drink, the most alcoholic course, college, and year, and some of the wildest stories – you’ll find it all below.

Before we begin, a note on data: it is difficult to work out how much people are drinking from a self-reported survey. Few consider their drinking in terms of units, but there aren’t many other reliable metrics from which it can be estimated. We went with the number of days drinking per week, with an additional question on how many days respondents drank specified numbers of units. We also asked how many days they had been drinking in week 4, in order to compare perception with reality (respondents were surprisingly on the money). In estimating intensity, we also looked at where people were drinking. As a result, this survey is not claiming to be a perfect encapsulation of every drop of alcohol consumed within Oxford. It’s a tour around attitudes, anecdotes, and habits in drinking.

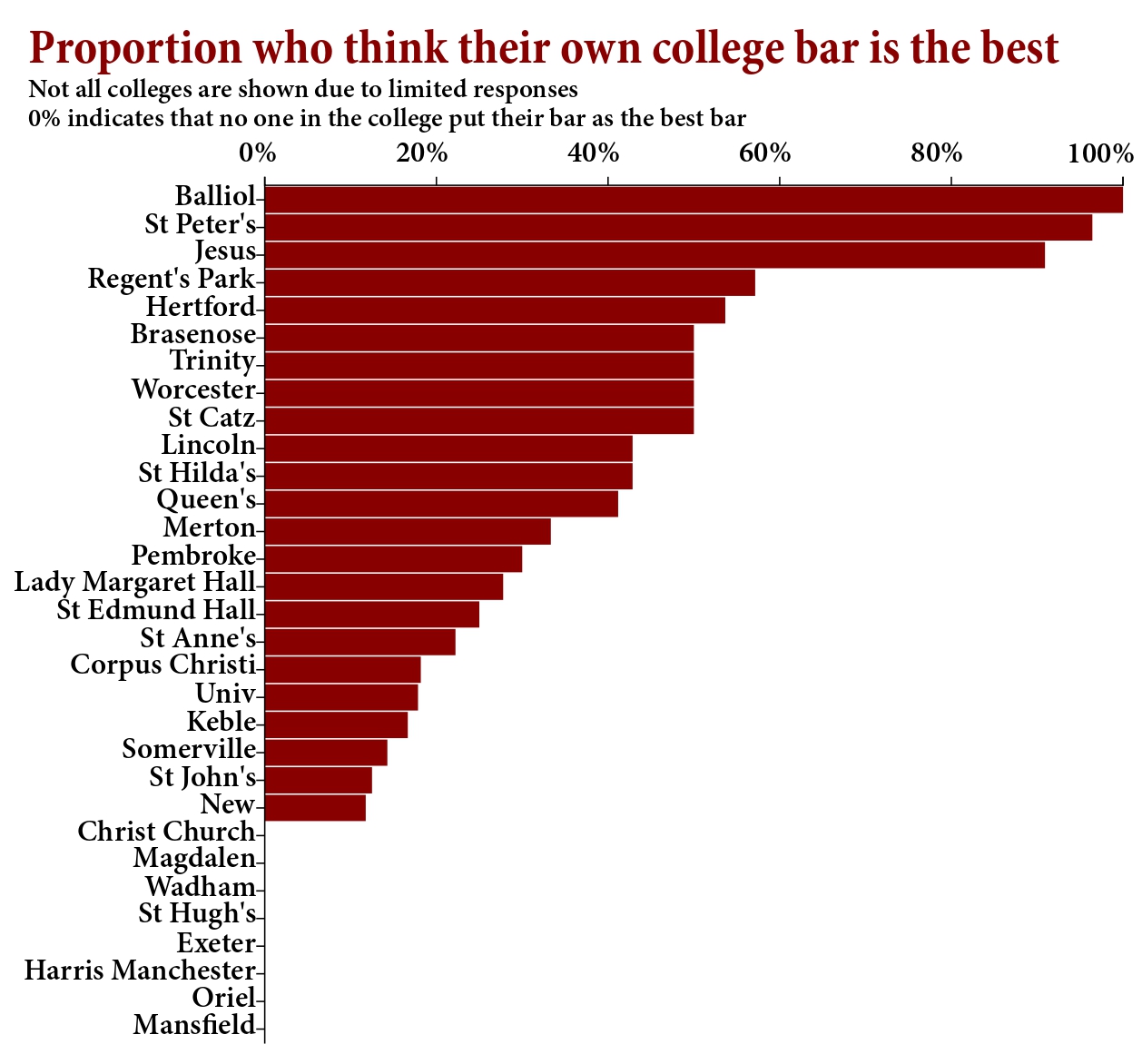

We received responses from every college, but excluded colleges from rankings when they were based on fewer than seven responses (Merton College, Mansfield College, St Catherine’s College, and Trinity College).

The colleges ranked

New College was the booziest college in Oxford, with the average student drinking on 3.62 days per week. Second and third place were taken by Jesus and Christ Church, closely following with 3.5 and 3.1 days respectively. Other strong contenders included St John’s (3.1), The Queen’s (2.9), Balliol (2.86) and St Hilda’s (2.71).

At the other end of the spectrum were Lady Margaret Hall (2.33), Corpus Christi (2.32), Keble (2.31), and St Edmund Hall (2.20). Ultimately, the three most teetotal colleges (or PPHs) were Regent’s Park (1.71), St Anne’s (1.78), and Worcester (2.19). For Regent’s, however, this may have just been efficiency, rather than sobriety; for three respondents, at least one of those days would exceed 14 units (the NHS recommended limit for a week).

Yet our survey also showed the gap between perception and reality. Our respondents thought the tipsiest colleges would be Balliol, St Peter’s, and – as our evidence revealed – the fairly sober Teddy Hall. It’s possible a great bar doesn’t always translate to more drinking…

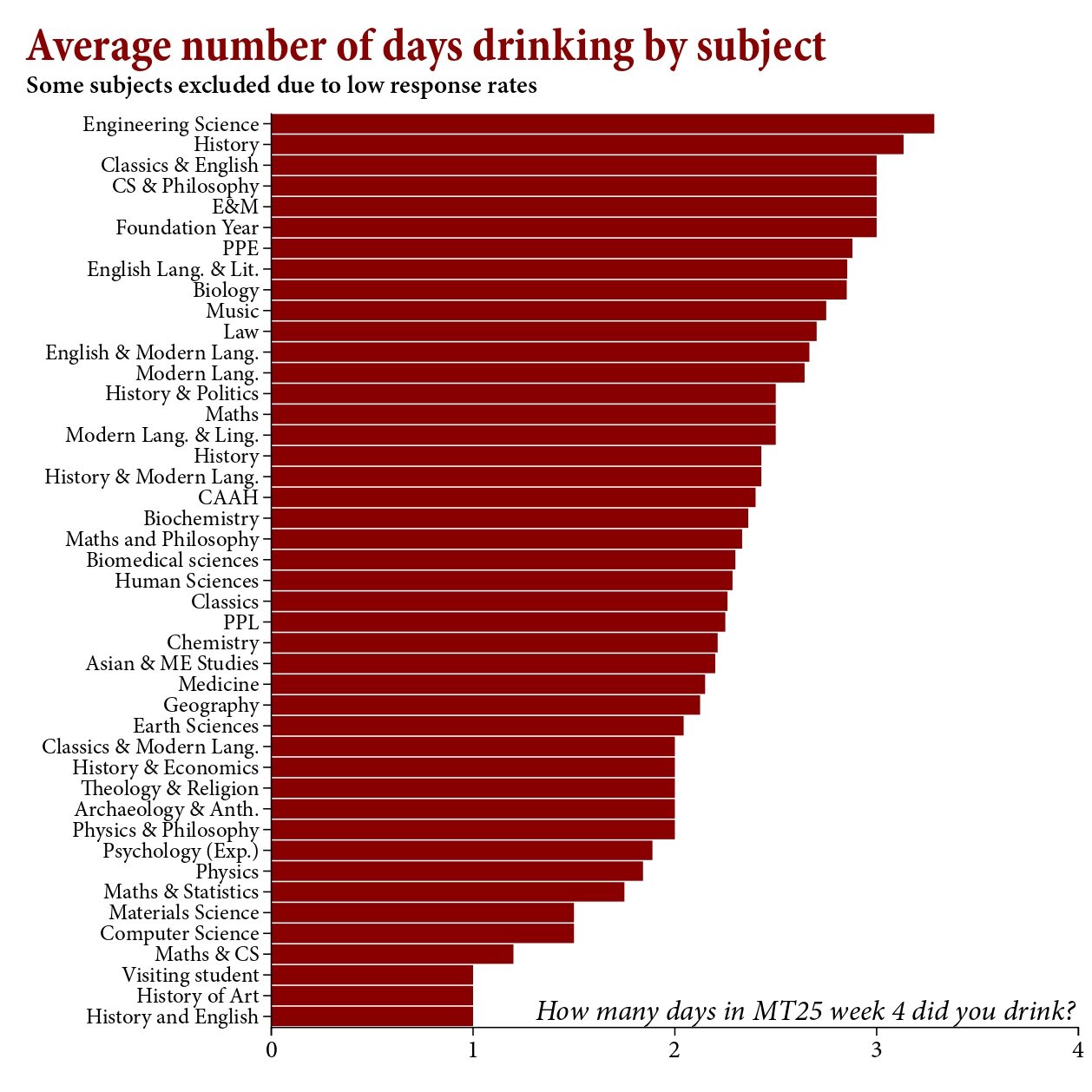

The courses ranked

Most alcoholic course was a different story. Stereotypes about hard-working STEM students and no-contact-hours humanities students were generally confirmed, but with some notable exceptions. The most sober course (with 1.86 days spent drinking per week) was Theology and Religion – perhaps that one day was a Sunday. Aside from this, the sciences dominated: Maths (1.90), Physics (2.05), Human Sciences (2.07), Biochemistry (2.09), Earth Sciences (2.11), and Experimental Psychology (2.11).

By contrast, climbing up the alcoholism ladder were Classics (2.65), the STEM-outlier Biomedical Sciences (2.65), English (2.85), History (2.88), PPE (3) and Law at an average of 3.08 days per week. The most intoxicated course, however, bucked all trends. With an average of 3.14 drunken days per week, Engineering Science students seemingly just can’t put the bottle down, topping the leaderboard as the drunkest degree. Not a great sign for our future buildings and bridges.

Location, location, location

So where exactly are our students doing all this drinking? Our data suggests that Oxford students are nothing if not consistent in their favourite watering holes. Despite all the buzz regarding rising pub prices, college bars and pubs are still essentially neck-and-neck as the city’s favourite locations. Respondents were asked where they drank the most, which we then compared to how many days they drank. Respondents who drank most in college bars drank an average of 3.04 days a week, narrowly beating pubs (3.01). Clubs trailed behind the two at 2.77 (must be all those blacked-out rounds of shots), followed by drinking in college accommodation at 2.48.

Despite stereotypes of lonely and overworked Oxonians, only 1.2% of respondents reported primarily drinking alone, half of whom were at Merton, and over half of whom reported drinking primarily due to emotions or essays. Statistics which, if nothing else, are worrying in their existence, but reassuring in their proportion.

What is interesting is not where people drink, but how little concern about cost seems to affect the choice. Weekly expenditure was nearly identical between mainly drinking in pubs (£23), college bars (£23), and clubs (£22). Even drinking in college accommodation averaged out to £16 pounds per week. The only real outlier was drinking alone (£8), which stubbornly resisted Oxford’s rapid inflation and remained alluringly affordable. In other words, Oxford students are seemingly willing to spend roughly the same amount regardless of location, suggesting that convenience, culture, and company matter more in choosing where to drink.

A Balliol bartender told Cherwell that people drink whatever is cheapest, which at Balliol is Hobgoblin. She did not have glowing things to say about the taste of the drink. On the other hand, a St Hilda’s bartender reported a broad range of popular drinks: “We started selling San Miguel this term and it’s ridiculously popular. The only thing that comes close to it is Stella to be honest – although on the cocktails side our passionfruit martini goes down a storm. We also get loads of requests for Guinness, so are bringing that onto draught for next term. Oh and of course – our cocktail and beer pitchers are some of our most popular offerings!”

When it comes to the pubs themselves, a clear favourite emerged. The Lamb and Flag swept the poll with 83 votes, firmly claiming its title as Oxford’s best pub for the second year in a row. The Four Candles (63), White Rabbit (56), King’s Arms (54), and The Bear (50) completed the top five. According to the most frequent and regular pub goers, the order reshuffled slightly, with the Lamb and Flag still secure, but The Bear climbing to second place, and White Rabbit rounding off a holy trinity that sits at a convenient triangle in Oxford’s dense centre.

Inappropriate imbibing

Unsurprisingly, all this drinking doesn’t always stay in pubs and bars. Respondents listed some of the most inappropriate places they have been drunk. The standout answer by a wide margin was tutorials, with around 40 students having experienced at least one tipsy tute. College chapels featured 13 times, with students reporting everything from doing a reading of a Bible verse drunk, to singing a solo at Evensong after a few too many. One respondent even claimed to have been drunk and locked inside their chapel at 3am. Some answers went even further, with students confessing to being drunk at the Master’s Lodgings, a Principal’s Collection meeting, the Sheldonian on matriculation day, and in one particularly memorable entry, the “gravel of the driveway of [their] tutor’s house”.

With a whopping 40 respondents confessing to turning up to tutorials mildly hungover, mildly dying, and in some cases, wildly still intoxicated, it seems Oxford drinking culture follows students straight from the club to the classroom. Some respondents describe all-bad experiences, like death warmed up. Others swore up and down it “makes your answers better” due to “pure adrenaline”. We can only hope that this was true for our one respondent, who described still being drunk during their last preliminary exam. Experiences reported ranged from petrifying to downright bizarre, with one student confessing to solving a problem in slow motion, only to have their tutor start “playing the f**king banjo at me to shame me”, and others describing a post-Halloween morning class where someone brought a cereal box instead of their laptop. One brave student soldiered through an entire tutorial before sprinting out to throw up down a grate on Ship Street. Their tute partner described them as “unusually subdued”.

Special mentions must be made for the May Day tutorials. Several beautiful May morning classes were interrupted by students stepping out to throw up, falling asleep, and at some points even almost fainting. The only comfort? It was May morning for everyone else in the class too.

The institution of the college bar

If you’re going to drink at college bars, you want to drink at the best ones. According to the respondents to our survey, that’s Balliol bar, St Peter’s bar, or Jesus bar. The draw might be obvious for Balliol – it was also voted best college drink, and its central location may account for 72% of its voters attending other colleges. A Balliol bartender told Cherwell that college bar crawls often come to a screeching halt when they reach Balliol, with all other college bars forgotten for the rest of the night.

It divided opinion, however, in our “Rant about a college bar” section. Its supporters were avid: “Balliol Bar might be the best thing about my university experience”; “Balliol Bar is so good and cheap and awesome”; “A shining beacon against corporations and late stage capitalism”. But its detractors were equally passionate. According to one: “Balliol Bar is OVERRATED. IT IS BUSY, IT SMELLS, AND THE FLOOR IS STICKY”. For another, the “blood red scheme” gave “slightly dodgy vibes much more in keeping with the college”. From a Balliol student, there was a different criticism: “Balliol bar is great for everyone who’s not Balliol since the reason it’s so cheap is because of the insane rent prices.”

A bartender at Balliol told Cherwell that the bar gets most busy on a Thursday night when it gets inundated with drunk rugby and netball players on crewdates and bar crawls. She highlighted the peculiar trend at Oxford of drinking being a punishment. People don’t drink to enjoy drinking, she said, they drink to get as drunk as possible. Comparing it to her home city of Glasgow, where, she said, people drink for enjoyment, the gamification of drinking was quite odd to her.

On the other hand, almost half of the votes for St Peter’s bar (48%) came from its own students, many of whom emphasised the importance of its remaining student-run. Across the survey, student-run bars were overwhelmingly popular. 82% of people preferred their bars to be run by students. In longer-answer questions, respondents praised student-run bars for the opportunities they provided, both for work experience and for paid work, in a university that bans term-time working.

Leo Kilner, one of the St Hilda’s bar managers, spoke to Cherwell about his experience behind the bar. St Hilda’s operates a hybrid system, with the College having taken over the bar after the COVID-19 pandemic. Students run the bar, while the College is in charge of stock and devising staff rotas. This is a relationship of autonomy and high expectations. The bar is expected to pay for itself, but the bar team is able to try all sorts of strategies to achieve this. At the moment, they are focusing on drawing in students from other colleges, taking advantage (for once) of Hilda’s less central location: “Everyone walks past Hilda’s on the way to O2 or the Bullingdon, so it’s the ideal pres spot.”

He considered student-run bars to have a more communal, convivial atmosphere than their professional counterparts, and to provide some of the cheapest drinks in Oxford, since they weren’t attempting to cover a professional salary. However, the downside of this was the strain on the bar team. Each member of the team had to play so many roles – bartender, events planner, strategiser – alongside an Oxford degree. They host live music nights, karaoke, Champions League football nights, and pool tournaments, making the bar an events space in its own right, not just for pres. Something appears to have paid off. Despite low uptake of the survey from St Hilda’s, the bar was the ninth most popular, and 70% of those who voted for it attended other colleges.

The student-led status of the Balliol bar was also a point of pride for the bartender Cherwell spoke to. She believed that student-run bars make for a better atmosphere, that people like knowing who is behind the bar, and that it is a great opportunity for the bartenders working there. She added that with student-run bars, there was no pressure to make a profit and that they can just be a space for people. She lamented the loss of student-run bars across the University.

In some ways, people felt more strongly about the best bar than the worst. On the latter question, there were double the number of blank responses than for the best bar. Still, the result was unequivocal – Wadham College bar is the worst college bar in Oxford, with 64 votes and numerous rants. Apparently, the quality brought out the poets in respondents, with numerous metaphors used to encapsulate its horror. A cafe, an NHS waiting room, and a youth club which had recently received its alcohol licence were all comparisons drawn to the Wadham bar. That, of course, was when it was open. The occasional 9.30pm closing time attracted considerable approbation, as did the bright lighting and the plastic cups. One Wadham historian put it in the most militant terms: “Wadham undergrads, we are supposed to be Communists. Seize the means of having a good old time.”

When approached for comment, Wadham College told Cherwell: “We have various spaces for our students in our dedicated Undergraduate and Graduate Centres. There is a JCR adjacent to the bar and an extensive lounge directly above the bar, where Bops take place. These combined areas form the social space for the students, not just the bar itself”. They reported being “in consultation with the SU [Wadham JCR] about extending and refurnishing the bar and JCR area. We expect to improve and revive the space over the Christmas vacation and in Hilary term.” Watch this space?

Drinking culture

The reasons Oxford students reach for a drink are, unsurprisingly, overwhelmingly social. A whopping 58.7% cited socialising with friends as their primary motivation, with 28.8% pointing to social events more broadly. Just 1.2% admitted to drinking for emotional reasons, 0.9% for dates, and a brave 0.5% confessed to alcohol-fuelled essay writing. Meanwhile, 8.4% abstained from drinking entirely.

The dominance of social drinking suggests Oxford’s booze culture is less about drowning sorrows or Dutch courage than it is about fitting in. When nearly nine in ten students are drinking primarily to bond with mates or navigate the endless carousel of bops, formal halls, and college bar sessions, abstaining becomes a social minefield. It’s hardly shocking that teetotallers remain a minority – though with 52 respondents choosing not to drink, there’s a quiet contingent opting out. While we emphasised that both drinkers and non-drinkers were welcome to fill in the survey, it’s also reasonable to assume that more people who drink will answer it, leading to a selection bias.

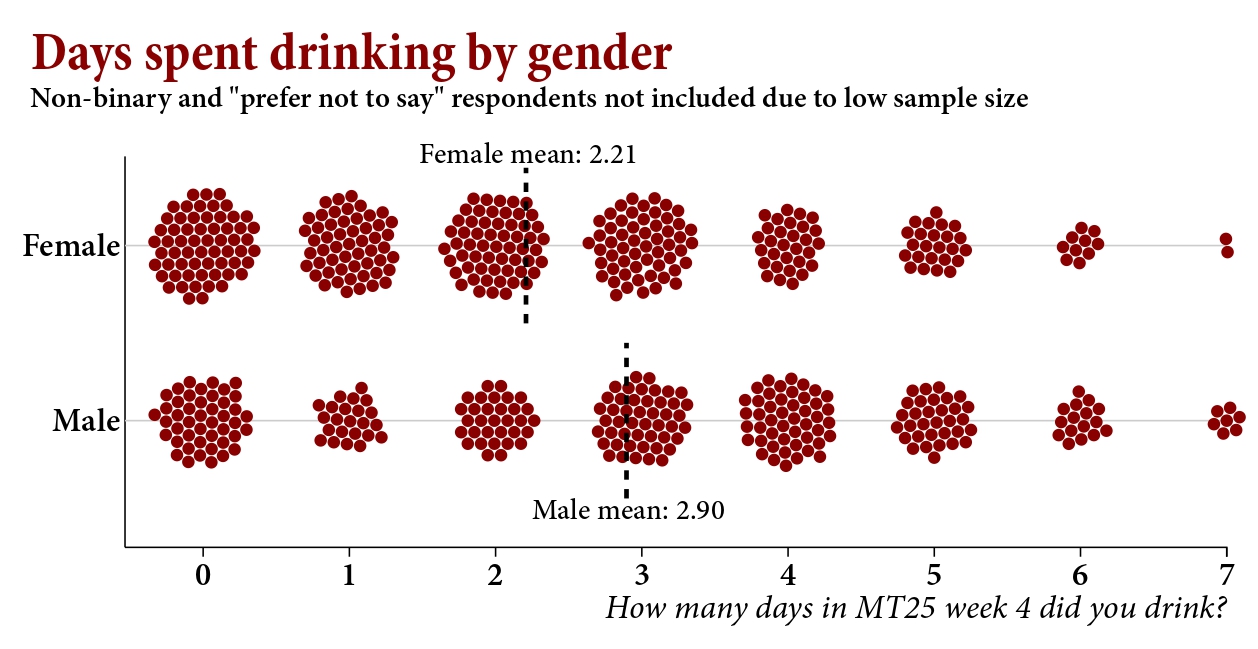

But how much are students actually putting away? The NHS recommends no more than 14 units per week, ideally spread over three or more days. Our survey found 181 respondents regularly exceeding this threshold on at least one day per week. The breakdown reveals a stubbornly male-dominated pattern: 71 men versus 55 women drinking over 14 units in a single day weekly, with the gender gap widening as frequency increases. Among those drinking heavily two days per week, it’s 21 men to twelve women. By four days per week, it’s exclusively male territory. And then there’s the outlier: one Christ Church third year drinking over 14 units seven days a week. If that is true (which Cherwell does doubt) we would like to express concern for his wellbeing. A Balliol bartender observed that during crewdates, girls were more likely to do shots of spirits and order doubles with mixers, whilst the boys drank mostly pints, making them “messier” by the end of the night.

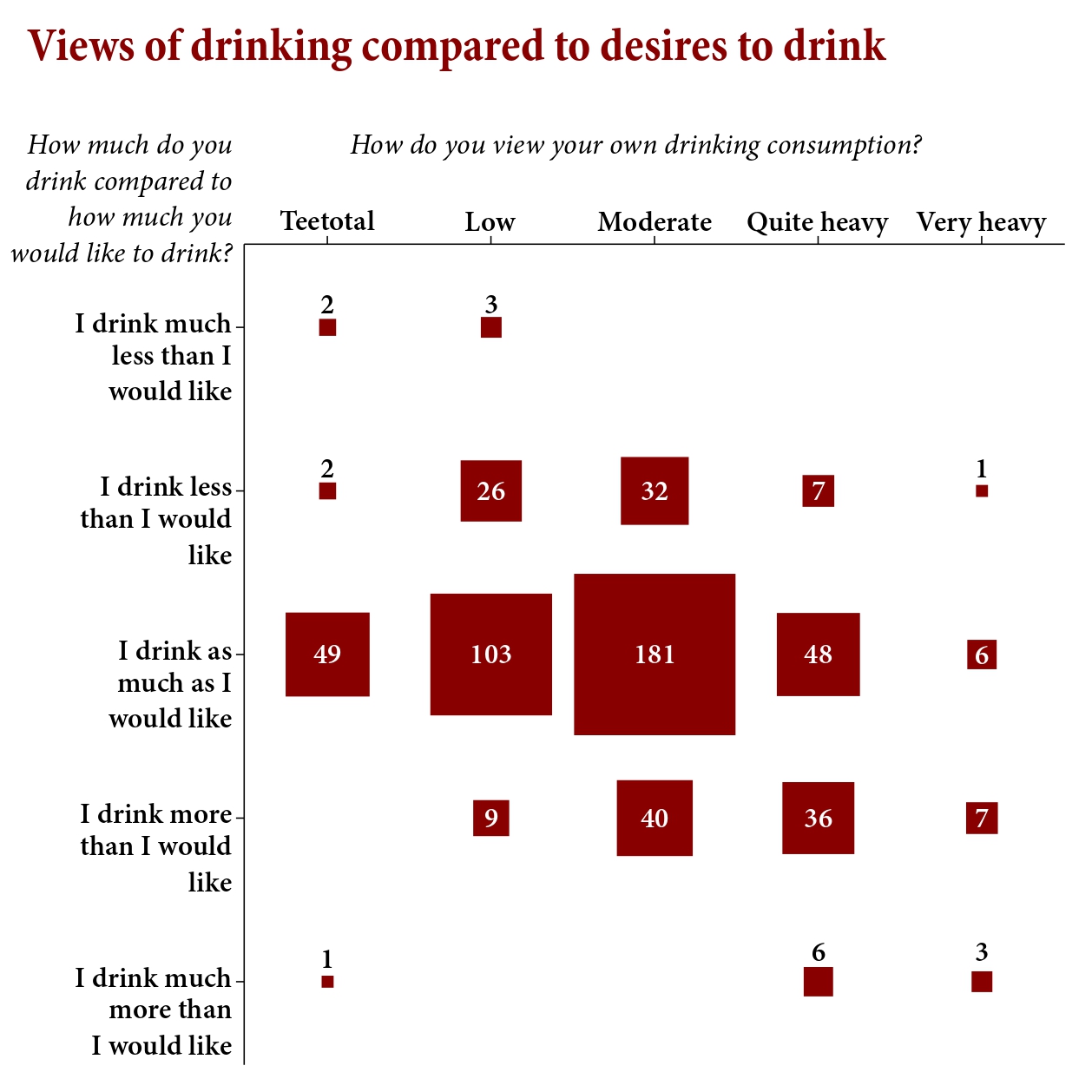

Yet self-perception tells a rosier story. Nearly half of respondents described their drinking as “moderate”, with 25.1% rating it “low”. Only 17.3% admitted to drinking “quite heavily”, and a mere 3% copped to “very heavy” consumption. This perception at least matches some reality. The “low” drinkers drank an average of 1.28 days in week four, the “moderate” drinkers an average of 2.9 days, and the very heavy drinkers reported drinking 4.8 days in the week. But while the amount drunk (and spent) increased, something decreased across these categories – satisfaction. 90% of teetotallers drank as much as they would like, and even moderate (73%) and quite heavy (50%) drinkers were broadly content. But of self-reported very heavy drinkers, 59% drank more or much more than they would like.

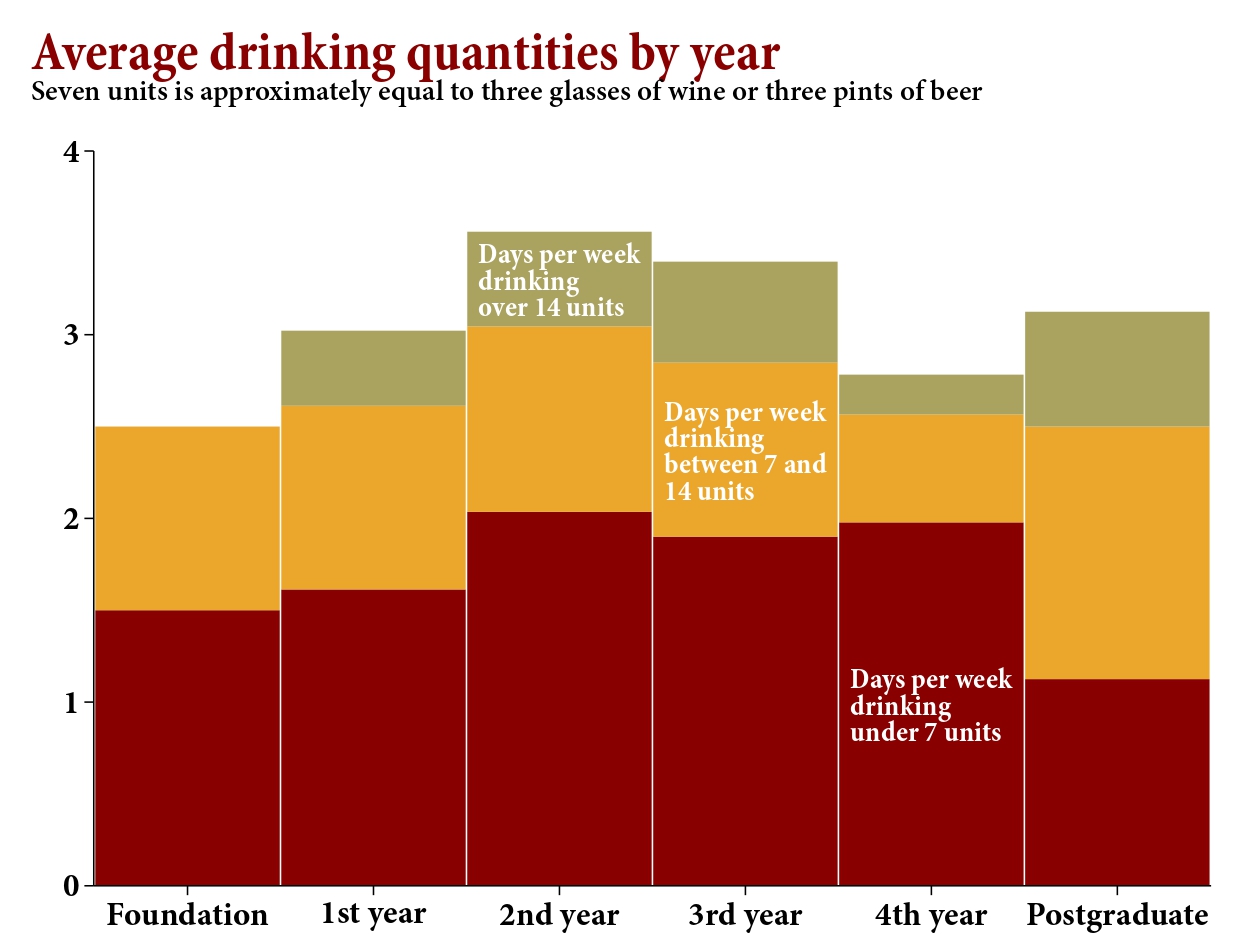

The university years follow a predictable arc. Over half of freshers (56%) reported increased drinking since arriving at Oxford, but this enthusiasm steadily wanes. By second year, 48% had ramped up their intake; by third year, 41%; and by fourth year, just 26%. In practice, this reduction appears to be limited to the amount being drunk. Between years, on average, there was just 0.3 days’ difference. Third-years reported drinking 2.85 days per week, while first-years drank 2.5. The places that each year reported drinking in most may account for a difference in perception, or amount, between them. First-years drank the most in college bars or college accommodation. Second-years were split fairly evenly between college bars and pubs. Third and fourth-years overwhelmingly drank the most in pubs, suggesting more social, low-key drinking meetups, rather than the club nights and crewdates of earlier years.

The reverse trajectory tells the sobering truth: only 12% of first-years had cut back, compared to 27% of second-years, 39% of third-years, and a majority 57% of finalists. Whether it’s impending Finals, encroaching adulthood, or simply growing tired of hangovers, Oxford students eventually learn to ease off the accelerator.

But for Kilner in the college bar, the first years weren’t necessarily swarming: “You notice there’s usually one friend group per year group that makes the bar their second home. The rest of the undergrads aren’t necessarily regulars though – especially the freshers, which is surprising. From what I’ve heard across the uni, there is a definite downward trend in drinking in general in our generation, and every new wave of freshers highlights it more and more. We aren’t able to take the freshers’ custom for granted anymore, which I think speaks a lot to how our generation are changing their approach to university.”

In terms of the change in drinking habits across the years, a Balliol bartender said that freshers were most likely to drink the infamous Balliol Blue, whereas third and fourth years stay far, far, away from it. She also noted that drinking was particularly prevalent in Freshers’ Week, when 18-year-olds, who don’t have to face their parents at two in the morning, and are very nervous at being at the formidable Oxford University, drink enough Balliol Blues and Reds to turn their insides purple. Although alcohol consumption decreases across the years, she said the booziest group she has ever served were a group of recent graduates in College for a reunion who were thrilled to be back in their old college bar drinking cheap drinks. Reliving the glory days…

Graph credits: Oscar Reynolds for Cherwell.