Oxford City Council approved their Local Plan to make Oxford a 15-minute city on 14th September 2022. In response, conspiracy theorists organised a mass protest. With some of the new traffic regulations now in place, it’s time for a deep dive into the conspiracist movement and its sunset legacy in Oxford.

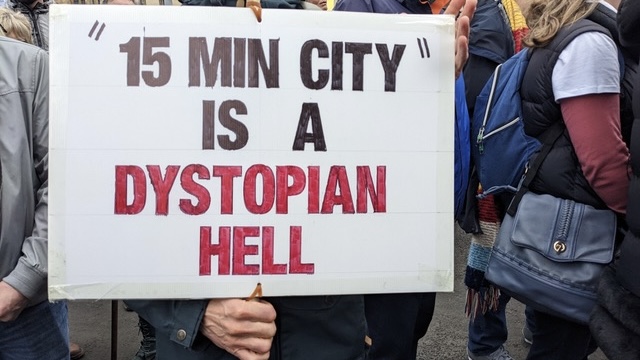

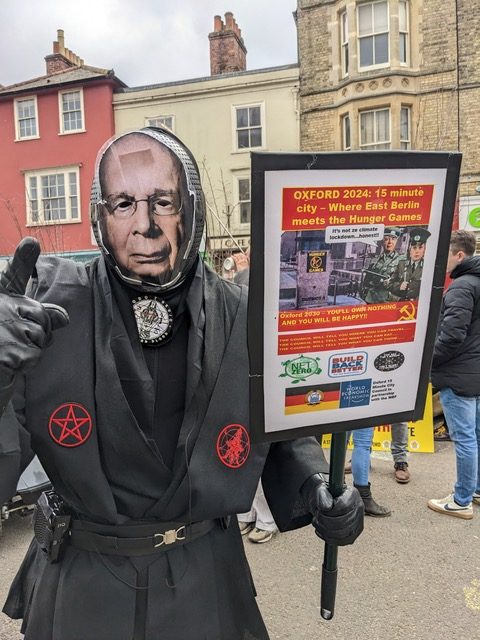

When students stepped outside their colleges on 18th February 2023, a strange sight may have confronted them. They might’ve seen someone in the guise of Karl Schwab (head of the World Economic Forum) and another of Greta Thunberg wearing an East Berlin border guard uniform. Or maybe their attention was caught by people carrying placards reading “No to Subversion, Surveillance and Control!”, “There is NO climate emergency” and “15 Min City communism – we do NOT consent”. These were the scenes of a protest against Oxfordshire County Council’s proposed traffic policies aimed at alleviating the city’s chronic traffic issues; making Oxford more like a 15-minute city.

What is the conspiracy theory?

The 15-minute city was originally an urban planning concept devised by Carlos Moreno, a professor at the Sorbonne University in Paris. Its aim was to have all key amenities accessible for residents within a 15-minute walk or bike ride. In Moreno’s own words, the driving force behind the concept was to “improve the quality of life for inhabitants”, ultimately “changing our traditional lifestyle based on long distances”. Oxford City Council endorsed this in their Local Plan of September 2022. When Oxfordshire County Council later introduced new traffic city controls in November 2022, conspiracy theorists conflated the two plans, fashioning the Council’s approach as a governmental ploy to restrict the freedom of movement – effectively, following the months of COVID-19 restrictions, a lockdown 2.0.

Professor Peter Knight, from Manchester University, has written extensively about conspiracy culture both in the United States and Europe. He told Cherwell that the conspiracy theory emerged at first from isolated blog posts by climate deniers. One online blogger wrote: “Oxfordshire County Council yesterday approved plans to lock residents into one of six zones to ‘save the planet’ from global warming. The latest stage in the ’15-minute city’ agenda is to place electronic gates on key roads in and out of the city, confining residents to their own neighbourhoods. . .Under the new scheme, if residents want to leave their zone, they will need permission from the council who gets to decide who is worthy of freedom and who isn’t.”

Following this, the theory was taken up by anti-lockdown activist groups and subsequently amplified by an existing web of conspiracy influencers. Knight explains: “Traffic control was reframed as a restriction of personal liberties. An existing network of anti-lockdown and anti-vaxx activists, as well as culture warriors tapping into conspiracist fears, pivoted towards traffic control schemes.” The BBC even reported that Emily Kerr, a member of Oxford City Council, was confronted by local residents about whether the measures were an attempt to curb personal freedom. Kerr said: “People have come up to me and said: is it true that we’re not going to be allowed out of our houses, that it’s going to be just like the coronavirus lockdown?”

It wasn’t all fringe conspiracy theorists though – the fear even got airtime in the House of Commons. Then Conservative MP Nick Fletcher called the 15-Minute City in February 2023 an “international socialist concept” during a parliamentary debate. According to Fletcher, the step threatened to “take away personal freedoms”.

Michael Barkun calls umbrella conspiracy theories “superconspiracies”. The 15-minute city conspiracy theories endorsed by those who protested in Oxford are part of a much larger paranoid narrative known as the Great Reset. The Great Reset was, in fact, the name given by the World Economic Forum to its agenda during COVID-19. It was a document setting out a new approach towards a fairer, greener version of capitalism. Conspiracy theorists saw it differently. To them, the Great Reset was a plan to use different forms of surveillance to keep people enslaved. For them, this included using technologies like digital cash, biometric facial recognition, and traffic cameras. During the pandemic, conspiracist ideas and protest became more widespread and that energy, Knight tells me, has been repurposed to new causes. Climate change is presented as a hoax intended, again, to keep the masses subservient.

It’s worth recognising that such concerns about the “globalist plots” are not just populist expressions of resentment but also a regurgitation of deeply held historical antisemitic myths about who secretly pulls the strings. Antisemitic conspiracy theories such as the The Protocols of the Elders of Zion, which claimed to expose a Jewish global plot but were quickly revealed as fraudulent (and later plagiarised), still influence discourse on certain pockets of the internet. These tropes reared their head in the slogans of some of those at the Oxford 15-minute city protest, a worrying reminder how concerns over something as innocuous as traffic policy can be exploited by those with more sinister agendas.

The Protest

Tensions over the Oxford City Council’s decision came to a climax in February 2023. Conspiracists from all over the UK took to the streets of Oxford, chanting, carrying placards, and even livestreaming the event on their social media accounts. Annie Kelly, journalist and reporter at the protest, told Cherwell about what she observed on the day. On the one hand, she recalled the “lively, carnival atmosphere” and the “strong sense of community” between campaigners where “lots of people knew each other”. On the other hand, though, the protest was poisoned by aggression and polemic rhetoric. Kelly described a cameraman from the BBC who was heckled by protestors. They shouted: “Shame on you!” Members from Patriotic Alternative, the far-right group described by The Times in 2023 as “Britain’s largest far-right white supremacist movement”, were also present on the fringes of the protest.

Big names on the conspiracist scene appeared too. Piers Corbyn, the conspiracy theorist brother of Jeremy Corbyn, and Lawrence Fox, the ex-GB news host, were amongst those who took to the stage. The former proclaimed that all forms of traffic zoning have “the same aim” – “to control you, to cost you, and to con you into believing in the man-made climate change story”. He linked the new Oxford measures with those in London: “break ULEZ and break Sadiq Khan.” One of the most circulated videos online from the protest was that by Katie Hopkins, the right-wing culture warrior. In a video published on her YouTube, Hopkins speaks to the camera on her way to the protest. She appears incensed by the media who want to “smear the people who are going to protest locking down a city into fifteen-minute zones”. When at the protest itself, Hopkins films the supposedly high numbers of police, taking their presence as evidence that the council’s decision is about more than just traffic controls. She wonders if “they’re practicing for when there is a low traffic network and they have to catch criminals.”

The demographic

The divide on 18th February was, unlike so many of those in Oxford, not a tale of town versus gown. Both locals and members of the University were united by their absence at the protests. Some protesters showed frustration at this, feeling abandoned particularly by the students. One woman said to Kelly: “I had hoped that the students would come and support us.” Here we see the tension between the right and higher education that so dominates our politics today.

In fact, the vast majority of campaigners travelled into Oxford for the event; they neither lived in nor were from the city. Kelly said: “If it had of [sic] only been locals, it would have been a much smaller protest.” Out of all those whom Kelly interviewed, only two were from Oxford. They were “very much a rarity”, also anomalous for their lack of knowledge about or investment in the conspiracy theories driving the protests. One of these local women said to Kelly: “We’re not anti-COVID … We’re just nice normal people.” She even clarified to Kelly that she had gotten “all of [her] jabs”. As a mobile hairdresser, she opposed the congestion charge not because she thought it a ploy by the global cabal to subjugate humanity, but because of the impact it would have on her access to her clients.

Yet the political demographic of the protesters can be hard to decipher. It’s hard to pin down the varying politics of some of the conspiracy theorists. A concern over sovereignty can lean in different directions: national sovereignty can lean right, heightening tensions over immigration, for example, whereas bodily sovereignty can lean left, towards new age spiritualism. The political scientists William Callison and Quinn Slobodian call this ‘diagonalism’. They write: “Born in part from transformations in technology and communication, diagonalists tend to contest conventional monikers of left and right (while generally arcing toward far-right beliefs), to express ambivalence if not cynicism toward parliamentary politics, and to blend convictions about holism and even spirituality with a dogged discourse of individual liberties.” The author of Doppelganger, Naomi Klein, calls this situation “a conspiracy smoothie”. She laments how the “far right” have become bedfellows with the “far out” today.

What now?

Today, some of the much lamented traffic regulations are now in effect. They began on 29th October 2025 with a temporary five-pound daily charge for motorists driving at certain times without a permit. The tax applies to only six roads in Oxford, including Hythe Bridge Street, St Cross Road, St Clement’s Street, Thames Street, Marston Ferry Road, and Hollow Way. It seeks to both ease the city’s chronic congestion and help alleviate the climate crisis.

There has been some backlash to the new measures. Open Roads for Oxford is the main organisation leading this. Their concerns are rooted not in conspiracism but rather the economic efficacy of the scheme and, according to their website, “the disproportionate impact on particular groups, including vulnerable people”. In their view, the congestion charge threatens to impact workers in low-paid sectors who offer mobile services and therefore often rely on their own transport for their livelihoods. Consequently, Open Roads for Oxford issued a legal challenge to Oxfordshire City Council over the scheme on 7th October 2025. It was, however, rejected by the council on 4th November 2025.

Yet from the conspiracy theorist groups themselves, no protests have followed those that took place in February 2023. The movement has dispersed, morphed, and shifted focus. Kelly said: “The movement is still around but more diffused than it was a few years ago. . . There is still very much a community but without the animating force of something like COVID it has slightly loosened over the years.” Now, without the animating force of COVID, supporters have moved onto other “passion projects”; seemingly innocuous concerns about 15-minute cities can easily be radicalised and spun into a wider narrative about the “globalist agenda”. For some, according to Kelly, this entails “branching off into educational co-ops”. For others, this involves the endorsement of the anti-vaxx agenda. Though this ideology has a long history, it has been given new vitality by the appointment of Robert F Kennedy Jr. as US health secretary and his Make America Health Again campaign. Conspiracy theories always evolve. They are like a hydra – you can slay one head, only for two more to appear.And so, when you step out of your college on 18th February this year, the streets should be free of Karl Schwab and Greta Thunberg impersonators – providing there isn’t another global pandemic.