How do you study art if you can’t see? In 2025, I was suddenly faced with this question, not out of curiosity, but the simple fact that half of my vision suddenly and significantly deteriorated. Perhaps it’s ironic that this strange period of my life began after an art exam (thank you, Mods). Health concerns aside, I suddenly had a huge art-shaped problem on my hands: I couldn’t see the art I was meant to be studying.

I would be lying if I said I knew exactly what happened to me, and to this day I’m still somewhat of a medical mystery to the Oxford Eye Hospital, which has quite frankly seen enough of me this year. The only certainty was that my eyes had changed. One was white, one was red. One was in constant pain, one was unaffected. One had 20/20 vision, and one could barely read the first row of an eye chart. As this malady set in, I was transported back to my 16-year-old self, plagued by completely different eye issues which demolished my self-esteem and threatened my health. Medical anxieties came flooding back. Was it something serious? Keratoconus, corneal dystrophy, or meibomian gland dysfunction? Would it leave scars? Would it last forever?

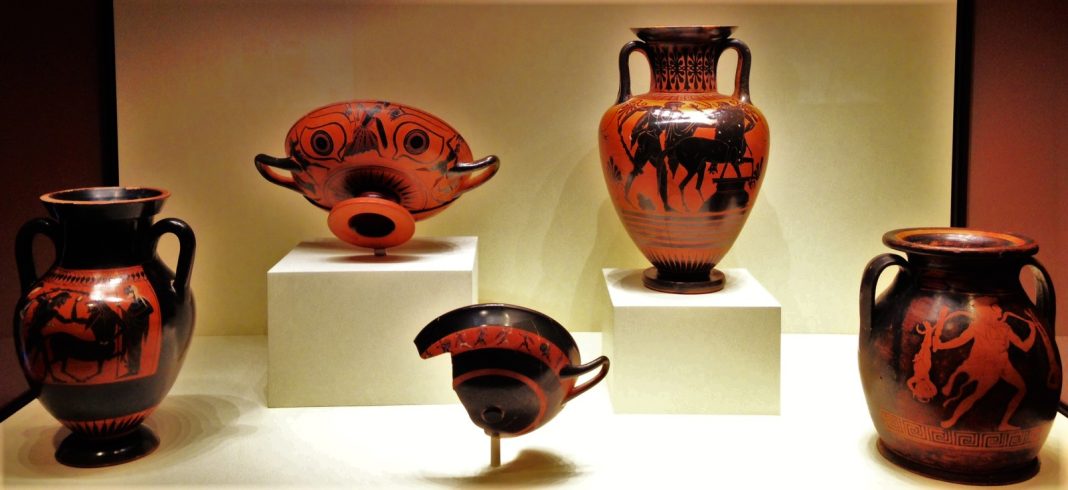

How do universities, and specifically art-related courses, accommodate for visual impairments? On a good day, the remedy of glasses, strong eye drops, and several compresses may have made my experience more bearable. But on a bad day, being presented with an undeniably beautiful image of a Greek sculpture on a computer screen only produced sharp pain and a blurred picture. Instances like these point to the absolute necessity of handling art in person, which I was fortunate enough to be able to do. Instead of being exposed to harmful screens, I could see objects in person and feel them to ascertain their shape, size, and texture. Yet, these opportunities certainly aren’t available to all, especially to those at universities with smaller endowments and archives. Likewise, while audio guides and large-print descriptions are available at some major galleries, such as the National Gallery in London, this is not a uniform policy across all British galleries. Some only provide audio guides for certain exhibitions, including the Ashmolean.

Art is anything but restrictive, and we can enjoy it with all of our senses. This is exactly what I sought to do once my sight began to falter. Far from the ‘immersive experiences’ in tourist-hell London, I found multi-sensory art in every walk of life. Cooking with Greek herbs transported me to the very land from which those blurry but beautiful statues originated. Musical accompaniments to exhibitions, like Art of Noise’s deliciously opulent Moments in Love complementing Tate Modern’s Leigh Bowery showcase, threw me headlong into pure artistic bliss, somewhat making up for the endless amount of squinting.

I also found art in what at first seemed mundane. The John Radcliffe Hospital, a short bus journey away from any of the University’s colleges, should have been a place for my eye-related anxieties to come to a head. Tense waiting rooms, uncomfortable operations, and news that can change your life in an instant. But, in my four-hour wait for an emergency ophthalmologist appointment, I found comfort in the art I came across unexpectedly. Enter NHS Artlink, the endeavour of Oxford University Hospitals to use the visual arts to reduce those same anxieties I had while nervously biting my nails in the JR. From floral wall-paintings by Angie Lewin in the Ambulatory Assessment Unit to Lisa Milroy’s Hands On drawing exhibition in the Emergency Department, the hospital is coloured with works by local artists, designed with the purpose to instill hope, even for just a moment. My often-frequented spot, the Eye Hospital waiting room, bears landscapes painted by Nicky Hirst and inspired by the Ashmolean’s Turner and Constable collection, reproductions of which juxtapose her paintings. I still couldn’t see them as well as I ought to, but comparisons to the familiar originals certainly helped.

The hospital’s main artistic attraction, however, is the Corridor Gallery. It functions as a mini-gallery itself, with temporary exhibitions held throughout the year. The curation is sensitive and speaks to the visitors of the hospital: recently, artist Marysa Dowling’s exhibition titled What We Carry showcased the experience of those with chronic pain, as channeled through photography and storytelling. In one photo series, we see joyful pet cats contrasted with polaroids of pillboxes and MRI machines. The neutrality of the display and the nostalgic sheen of polaroid certainly emphasises the constant presence of chronic pain.

Until 17th January 2026, the Corridor Gallery is also host to Oxford-based artist Claire Venables’ collection of oil paintings titled Looking at Glass. This exhibition is similarly one of contrasts, as Venables explores the relationship we have with everyday objects, from fruit and flowers to conical flasks. Each painting employs a blue-dominated colour scheme, complementing each other greatly, and once again speaking to the uncomfortable normality of illness in our everyday lives. In a state where I couldn’t see clearly, I saw truth in these paintings. My visual impairment wasn’t something I could turn off, or even forget about for just a moment, constantly faced with it until I shut my eyes at the end of the night.

A year later, and after a long treatment of steroids, my vision has fortunately recovered, but the anxiety remains. I often think of the other patients who continue to endure the four, five, even six hour waits for appointments at the Eye Hospital, riddled with the same anxiety. I only hope that the art dotted around the JR brings them as much hope as it did for me.