How do we make hard choices? Not the choices which are hard for us to make – because the right choice is psychologically difficult – not choices between options which we have incomplete information about, or choices that are incomparable. No. Hard choices are decisions between options neither of which is better, nor are they equally good. Let’s say, should I become a commercial lawyer or a philosopher? These options – in the words of Professor Ruth Chang – are on a par.

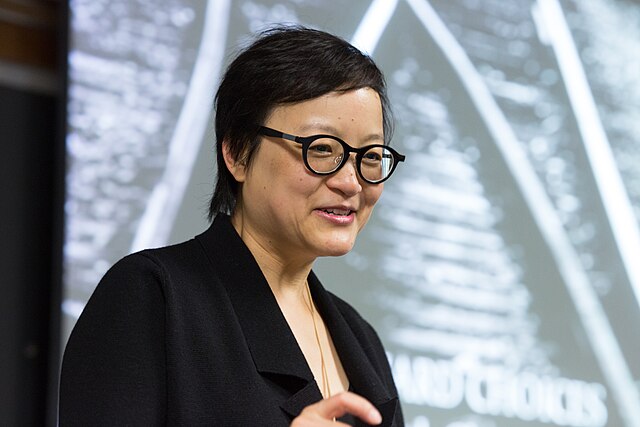

Chang is the Chair and Professor of Jurisprudence at the University of Oxford and a Professorial Fellow of University College. Law students will be familiar with some of the previous holders of her post at Univ: H.L.A. Hart, Ronald Dworkin, John Gardner. Before coming to Oxford, she was Professor of Philosophy at Rutgers University in New Jersey, United States. She has held visiting positions at Universities of California, Los Angeles and the University of Chicago. She holds an AB from Dartmouth, a JD from Harvard, and a DPhil from Oxford, during which she held a Junior Research Fellowship at Balliol.

We had lunch in Univ’s beautiful SCR on a soggy Wednesday in the middle of Week 3 Hilary, where I had some chicken and potatoes, and a very delicious chocolate pudding.

“Take this pudding you’re eating”, she says. “What’s another dessert that you really like?” “Strawberry ice-cream”, I said. “Let’s imagine I asked you to choose between these two, what would you do?”, I’m not sure which I would pick. Neither seem to be obviously better than the other. Yet, Chang says, it also cannot be that these two desserts are equal in tastiness. Contrary to what some philosophers say, it does not seem right that we should simply flip a coin. These two desserts, then, are on a par. As there is some qualitative difference between them, I’m not simply able to say that one is better than the other.

This may seem intuitive. However, if she is right, the implications of her theory are enormous.

“Our entire landscape of normativity is wrong”, she tells me. Everything from ethics, law, to economics rests on this fundamental assumption of “trichotomy”. That, given two values, one must be better than, worse than, or equal to the other. This might be true of quantities such as lengths, weight, and volume, but it is not true of values. Chang says we should instead be tetrachotomists, that we should allow the possibility of parity alongside greater, equal to, and less than.

What does this all have to do with AI? To understand the implications of her work, we must first understand what is known as the Value Alignment Problem. In other words, how do we make sure AI is not misaligned to our values? To grossly oversimplify, researchers are having a hard time making sure that AI systems behave in an appropriate way. For example, having been told it will be removed, Anthropic’s Claude resorted to blackmail. ChatGPT appears to amplify global inequalities. xAI’s Grok has continued to generate non-consensual sexualised images despite curbs. The most extreme example is that, one day, these models could be used to make weapons of mass destruction (if they are not capable of it already), and AI companies are struggling to make sure that they won’t.

The goal, therefore, is to make sure that AI systems, as they get increasingly powerful and intelligent, have the same values that we do – values like honesty, compassion, fairness – and respect us and our lives so they won’t come around to destroy our world. This might all sound fanciful and sci-fi-y. However, the risk is real. It is serious enough that loss of control of AI systems was included as a potential threat in the Security Service’s (MI5) annual threat update in October of last year. Philosopher Nick Bostrom has called it “the essential task of our age”.

Chang doesn’t pretend that she has the solution to the entire problem. “No, what I’m working on is a very small part of it.” But she’s not optimistic about the current trajectory of AI research. “If we keep going down this road, we are definitely going to get AI misalignment.” Why? Because current AI systems fundamentally assume value trichotomy, she explains. They don’t recognise hard choices, and they simply force a solution, which may not be the solution that we want or that we would have made.

I push back on this. I ask her, “okay, let’s say you’re right. But even in this misaligned world, isn’t it true that the AI will only make ‘misaligned’ or bad decisions in hard cases, and its decisions will be fine in most cases, or the easy cases?” But that’s not right, Chang replies. “Think of your parents.” We’re both Chinese. “Your parents, whilst well-meaning, might have this idea of who you are and what type of person you should become: you should grow up to be a doctor and make lots of money and make your family proud, you should marry this girl, or you should move to this city.”

It’s not that these are bad choices. Indeed, if the options are on a par, it would not be irrational for us to choose either. Rather, it is that we would not be living up to our fullest potential if we simply listened to our parents on everything: we are in some ways sacrificing our rational agency. Instead of fullest versions of ourselves, we would be the version of ourselves that our parents want. This might be okay, but it is certainly not a good idea if we swap parents for AI. When options are on a par, forcing a ranking is itself a kind of value distortion; and acting on that distortion at scale becomes misalignment.

Chang insists this isn’t all doom. “Even though it is going to be expensive, there is a way to fix this.” How? She explains that we need to teach the models to first recognise hard choices, and to present them to us. The technical details are unimportant here. But once we are presented with these choices, how are we to choose? After all, isn’t the whole point that these choices are hard?

“Commitment”, Chang says. By committing to one of the choices of two that are on a par, we are able to generate reasons which weigh in favour of one option over the other, even if the objective reasons ‘run out.’ Once I am committed to becoming a philosopher, I have more reasons to be a philosopher than a lawyer by virtue of that commitment, which itself creates a (will-based) reason. We are able to do this, Chang says, because of our rational agency. Machines, however sophisticated, can’t exercise that normative power for us. We don’t have to commit, however. We can also just drift into a choice of least resistance. “But that would be a shame”, she says.

I then asked her, if Sam Altman (CEO of OpenAI) walked into the room right now, what would she want to tell him? “The fundamental structure of these models are wrong”, she explains. They need to recognise that values, unlike things like lengths, can be on a par; this requires a fundamental rewiring of their architecture. “Think of it this way”, if we made these models without the possibility of equality, so that one choice always has to be better or worse than the other, we would obviously change their structure so that it recognises that sometimes two options are equally good. If she is right about parity, then we should make the same sacrifices, no matter the cost.