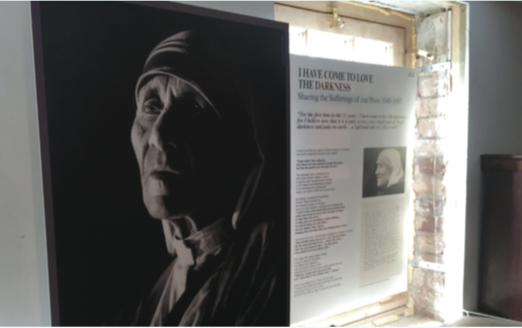

Mother Teresa is set to be canonized as a saint in the Roman Catholic Church in September this year, as announced by Pope Francis this past March after he confirmed her second miracle, the healing of a man with multiple tumors. In honor of the an- nouncement, Johnny Church at St. Aloysius’s Church on Woodstock Road has set up a new exhibition documenting her life and works. The exhibition was opened on April 18 in the Oxford Oratory following a special Mass and will be open until April 30. The exhibition includes striking images from the Nobel Peace Prize winner’s youth and family life in Albania, her time spent learning English in Ireland, and her early years as a missionary. These evocative photographs are balanced by objects that connect the visitor more materi- ally to her lived experience, including things such as her sari, a selection of her letters and a handwritten prayer book. Other points of interest include images from her visit to the Oxford Union and her meeting with Princess Diana, who died only a few days before Mother Teresa died during one of her mis- sions in the Bronx, NYC in 1997. Surrounded by such emotional, intimate photographs of her labors, one can’t help but be awestruck by the devotion that Mother Teresa had to help- ing others, despite any disputes concerning her faith that have arisen since her beatifica- tion in 2003 by Pope John Paul II. St. Aloysius’s Church reminds its visitors that while we sometimes focus only on the extraordinary deeds of society’s heroes, we often forget that such figures were also ordinary humans fac- ing human challenges.

Sculpture To Die For

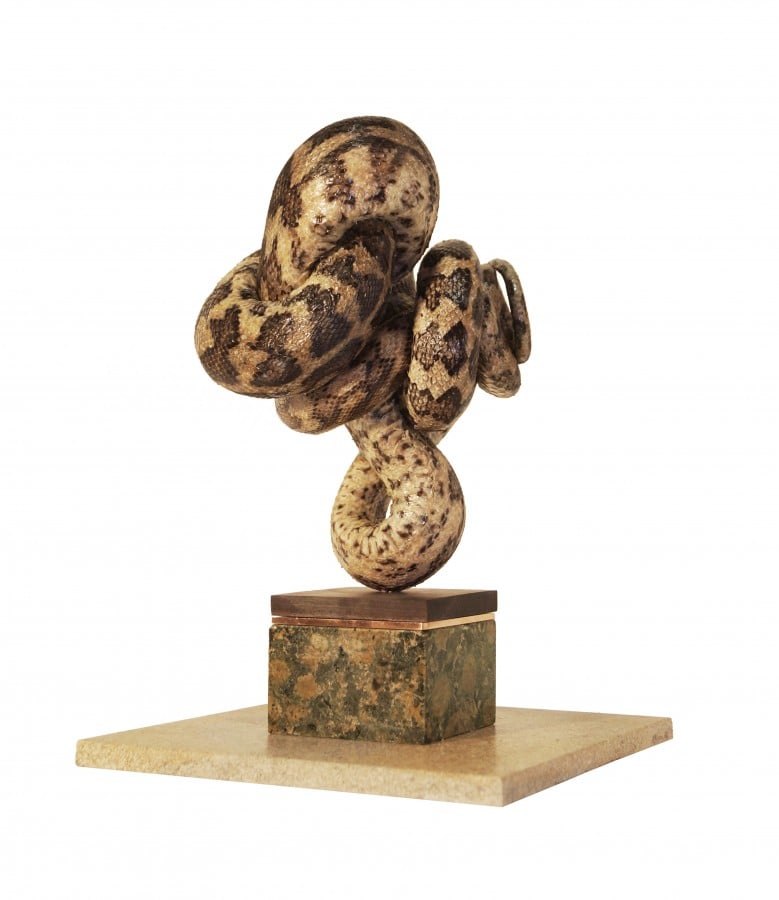

On a gloomy and macabre rainy day over the vacation, I found myself being led down into the basement studio and workspace of Polly Morgan, arguably the most famous taxidermy-artist in Britain. Having only recently moved into this new space from her old studio in Hackney, she apologises for ‘not really having anything to show me’ (most of her work is in boxes waiting to be unpacked) but as we walk in, the yellow and white heft of an albino python’s corpse defrosting on a worktable catches my eye. A glimpse into one of her freezers reveals another row of sinuous and coiled cold bodies. ‘Nothing to show?’ I wondered. I had only just arrived and already I had been shown more of her ‘materials’ than I had bargained for.

Far from being a cold-hearted butcher itching to get her scalpel into her next corpse, she gives off an aura of warmth and affability, able to laugh at some of the more unconven- tional aspects of her profession. So obviously, my first question was, ‘why taxidermy?’

Initially studying English at Queen Mary University of London, Morgan graduated at 23 years old with the realisa- tion that her passion was not really in literature. Indeed, she was struggling to understand where her passion lay. While managing the Shoreditch Electricity Showrooms bar, she took courses in photography and journalism with the only outcome being that she learned that photography wasn’t for her and that she never wished to work in an office. She began to worry that for the rest of her life she would remain a ‘“jack of all trades, master of none.”

Then Morgan stumbled into taxidermy, merely trying it out once and finding herself captivated by it. After taking a day course from Scottish taxidermist George Jamieson, she knew she had found something that really gripped her. Speaking about her feelings about entering what was for her a previ- ously unexplored field she said, “I knew I could be fearless.”

Morgan was certainly unafraid to put her own personal twist on taxidermy. The art itself had fallen to the far reaches of conventionality and popularity since its heyday in the Vic- torian era, but Morgan, as well as many other contemporary artists, resurrected it from its cultural death much like she reawakens the corpses of the animals she works with. Her art features the bodies in uncanny situations, positions which recall scenarios that a viewer might briefly recognise com- bined with a completely foreign and sometimes unsettling element. When her artistic career was at its inception she had to scavenge for corpses, taking what she could get from vets and breeders. Earlier in her career, small birds and road-kill were easiest to acquire (Morgan has always kept from actively killing animals for the purposes of her art). An early work but one of her favourites, Still Birth, features a dead chick hang-

ing from a balloon suspended as if in flight in a glass bell jar. Birds have continued to feature in her work throughout her career but a thirst for new artistic challenges and greater fame have brought her the opportunities and desires to tackle new challenges. Morgan’s most recent works feature the bodies of snakes as twisting and twining sculptures, turning in on and over themselves and forming beautifully abstract still life images in the process.

With Morgan’s artwork, there seems to be a sense that the bodies are not revitalised but repurposed. They combine with the other mediums she uses to create her sculptures to form a more complex image than that of a traditional stuffed animal. Morgan hopes that her sculptures do remind people of things they have seen before but she insists that there isn’t a great deal to understand about her art. “The worst art,” she says, “is stuff like a one-liner.” She says she is not in the busi- ness of creating visual puns and it is not her mission to encode messages in her art. She claims a ‘synaesthetic instinct’ when it comes to creating art, an innate sense of the combination of the right texture, the right colour and the right use of space. Her art poeticises traditional taxidermy and renders it more aesthetically pleasing to the eye.

The general public might look at some of Morgan’s work and wonder what sort of depraved mind thought up such a thing, and she wouldn’t be able to enlighten them. “When I made them I couldn’t tell you what I was thinking,” she confesses and personally, part of me doesn’t care. The unexpected beauty to be found in death is quite pleasantly surprising enough to satisfy these eyes.

EXCLUSIVE: Oxford Union Trinity term-card

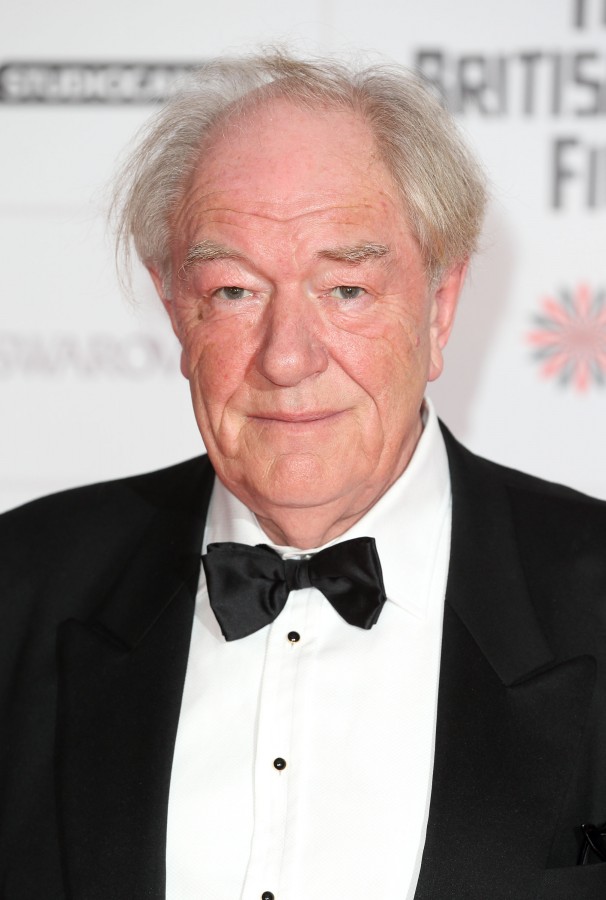

Sir Michael Gambon, Naomi Campbell and Ben Affleck are just some of the big names that will appear at the Oxford Union this term, Cherwell can reveal. The full term-card will be arriving in pidges across Oxford tomorrow, but for now, here’s an exclusive preview of what you can expect. Click on the thumbnail images below for more information about each speaker.

The seven Thursday debate titles, and the speakers attending them, will be as follows:

Proposition

Prof. Peter Atkins – Emeritus Professor of Physical Chemistry at the University of Oxford

Dr Nina Ansary – Bestselling author, historian, and leading authority on women’s rights in Iran

Opposition

Sheikh Dr Usama Hasan – Senior Researcher at the Quilliam Foundation, a think-tank specializing in human rights and counter-extremism.

The Very Revd Prof. Martyn Percy – Dean of Christ Church since October 2014.

Proposition

Proposition

Peter Lilley MP – Conservative MP for Hitchin and Harpenden since 1983.

Dr Paul Oquist – Minister of the Nicaraguan Government, and Secretary of Public Policy.

Opposition

Prof. Bruce Pardy – Professor Environmental Law at Queen’s University, Canada.

Paul Bledsoe – President of Bledsoe & Associates, a global public policy firm specialising in climate change.

Proposition

Stephen Hale OBE – Ceo of Refugee Action, a UK charity which provides legal, financial, and practical support to refugees.

Barry Andrews – CEO of GOAL, an international aid organisation which has spent over £10m on humanitarian programmes.

Opposition

Dr Thérèse Coffey MP – Conservative MP for Suffolk Coastal since 2010.

Dr Andrew Morrison MP – Conservative MP for South West Wiltshire since 2001.

Proposition

Gideon Levy – Award-winning columnist for Haaretz whose writing focusses on the Israeli occupation of the West Bank and Gaza.

Salma Karmi-Ayyoub – Criminal barrister and external consultant for Al Haq, a Palestinian human rights organisation.

Prof. Padraig O’Malley – A specialist in divided societies, he was instrumental in the Northern Ireland peace process.

Opposition

High-Profile Israeli Official – Due to the sensitive nature of this speaker’s security arrangements, the Union will be releasing their details nearer to the time.

John Lyndon – Executive Director of OneVoice, an international grassroots movement which supports a two-state solution by amplifying the voices of mainstream Israelis and Palestinians.

Prof. Raphael Cohen-Almagor – An Israeli academic, he has involved with the campaign which exchanged the captured Gilad Shalit for 1,000 Palestinian prisoners.

Proposition

Prof. Sir Ian Wilmut OBE – Lead scientist of the research team which cloned Dolly the Sheep, he was knighted for his services to science in 2008.

Prof. Julian Savulescu – Director of the Oxford Uehiro Centre for Practical Ethics, and one of the world’s most outspoken philosophers on ‘procreative beneficence’.

Opposition

Prof. Barbara Evans – Proessor of Law, George Butler Research Professor, and Director of the Center for Biotechnology at the University of Houston.

Prof. Normal Frost – Paediatrician and leading bioethicist, he was part of President Clinton’s Health Care Reform Task Force.

Proposition

Danelle Dixon Thayer – Chief Legal and Business Officer of Mozilla, a free-software community whose products include the Firefox web browser.

Naomi Wolf – Acclaimed author, journalist, and feminist, first coming to prominence as the author of The Beauty Myth.

Opposition

Matthew G. Olsen – Director of the US National Counterterrorism Center 2011-2014, he was formerly Head of the Guantanamo Review Task Force.

Air Marshal Chris Nickols CBE – Chief of Defence Intelligence 2009-2012, and former Assistant Chief of the Defence Staff for Operations.

Proposition

Gisela Stuart MP – Labour MP for Birmingham Edgbaston since 1997.

Lord Michael Howard QC – Leader of the Conservative Party 2003-2005 and Home Secretary under Sir John Major.

High-Profile Business Executive – Senior business executive who will soon announce their support for the Vote Leave campaign.

Opposition

Alex Salmond MP – Scottish National Party MP for Gordon since 2015.

Yvette Cooper MP – Labour MP for Normanton, Pontefract and Castleford since 1997.

Lord Michael Heseltine, Ex-President – Conservative stalwart who served as Deputy Prime Minister under Sir John Major, and Secretary of Defence under Margaret Thatcher.

Other speakers:

1st Week

Ambassador Mark Regev (Tuesday, 1st Week) – Ambassador of Israel to the United Kingdom

Mikhail Khodorkovsky (Wednesday, 1st Week) – Exiled Russian Businessman and Dissident

Dr Vitali Klitschko (Thursday, 1st Week) – Mayor of Kiev

2nd Week

Michael Eavis CBE (Monday, 2nd Week) – Founder of Glastonbury Festival

Clarence Seedorf (Tuesday, 2nd Week) – Retired Dutch footballer and manager

George Foreman (Wednesday, 2nd Week) – Former world heavyweight champion

3rd Week

Geri Halliwell & Christian Horner OBE (Monday, 3rd Week) – Former Spice Girl, and Formula One Team Principal

Liv Boeree (Tuesday, 3rd Week) – #1 Female Player on the Global Poker Index

Anthony Geffen (Tuesday, 3rd Week) – Sir David Attenborough’s Filmmaker

Jeroen Dijsselbloem (Wednesday, 3rd Week) – Dutch Finance Minister and President of the Eurogroup

Bangladesh Panel Discussion (Saturday, 3rd Week)

Dr Kamal Hossain – Former Law and Foreign Ministers

Dr Gowher Rizvi – International Affairs Advisor to the Prime Minister

Prof. Sir Paul Collier CBE – Professor of Economics and Public Policy at the Blavatnik School of Government

Prof. Mthuli Ncube – Professor of Public Policy at the Blavatnik School of Government

http://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qqXUpe3jlkA

4th Week

Candide Thovex (Wednesday, 4th Week) – Word-class freeskier

http://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yKP7jQknGjs

5th Week

Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy (Sunday, 5th Week) – Academy Award-Winning Filmmaker and Activist

Chief Rabbi Ephraim Mirvis (Monday, 5th Week) – Chief Rabbi of the United Hebrew Congregations of the Commonwealth

KT Tunstall (Tuesday, 5th Week) – Award-winning singer-songwriter

IBM Watson (Wednesday, 5th Week) – Cognitive technology platform and Jeopardy! winner

Kate Beckinsale (Friday, 5th Week) – World-famous actress

http://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KDtxQRH8aI4

6th Week

James Blunt (Tuesday, 6th Week) – English singer-songwriter and activist

Ken Livingstone (Wednesday, 6th Week) – The First Mayor of London

http://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oofSnsGkops

7th Week

Allyson Felix (Monday, 7th Week) – Former Olympic sprinter

Dr Riek Machar (Tuesday, 7th Week) – Vice President of South Sudan

Theo Paphitis (Tuesday, 7th Week) – Entrepreneur and former Chairman of Millwall Football Club

Jerry Springer (Wednesday, 7th Week) – American TV presenter and talk show host

http://https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=asDkcyafZPo

8th Week

Craig David (Monday, 8th Week) – English singer-songwriter. He will be performing

Lord Michael Dobbs (Tuesday, 7th Week) – Author of House of Cards

Gabrielle Aplin (Wednesday, 8th Week) – One of today’s best upcoming singer-songwriters

To be confirmed

Naomi Campbell (TBC) – Supermodel and activist

Sir Michael Gambon CBE (TBC) – Film, television and theatre actor

Baroness Elizabeth Butler-Sloss GBE (TBC) – First Female Lord Justice of Appeal

Adel al-Jubeir (TBC) – Minister of Foreign Affairs of Saudi Arabia

Shehbaz Sharif (TBC) – Chief Minister of Punjab

Andreja Pejić (TBC) – Transgender model and activist

Ben Affleck (TBC) – World-famous director and actor

Guy Verhofstadt (TBC) – Former Prime Minster of Belgium

Lindsey Vonn (TBC) – Former American ski racer

Paula Radcliffe MBE – British long-distance runner, current women’s world-record holder in the marathon

Sir John Major KG – Former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

A referendum on the NUS

When we arrived in Brighton, wearing our green “RON them all” t-shirts, people initially thought we were just like them, but having a little bit of fun by satirising the way in which NUS election campaigns are conducted – through t-shirts and hats, apparently. Many candidates came up to us, and, with a wink and a nudge, asserted that we obviously weren’t going to actually RON them, and that they definitely deserved our first preferences.

Later, a member of the NUS’ National Executive Council, who also is a member of the National Campaign Against Fees and Cuts faction, mocked a speech that I made calling on the NUS to remember that it represents all students, and to act as such. She, speaking for another motion, sarcastically quoted what I had said about being moderate, and finished it off with “only joking”. The same person later tweeted her puzzlement that anyone would applaud the candidate for Block of 15 who had admitted that he was a Conservative and wanted the NUS to represent a range of views.

It is these attitudes – the absolute incomprehension that there exists any student who exists outside of this sphere – or indeed who is apathetic about politics – that pervade the NUS, and mean that these days it is nothing more than an echo chamber for a particular point of view, or a particular set of buzzwords. Indeed, nothing sums up the naivety and political narrowness of the NUS more than when Shelly Asquith, the newly re-elected Vice President for Welfare, alluded to Oh Well Alright Then’s leaking of her bizarre campaign strategy by calling us a group of “Tories”. Three of us are Lib Dems, one of us is Labour.

But it is more than just an attitudinal divide between the NUS and the ordinary student – it is the fact that the organisation is so patently unreformable, and refuses to listen to any criticism of it. This Conference passed motions seeking to put restrictions on Yik Yak and other social media, lobbying to stop GCSE Maths and English from being compulsory, and crucially, overwhelmingly voted against One Member One Vote, a democratic reform which would have given every one of the NUS’ 7 million individual members a vote in electing its national sabbatical officers – by contrast, only 372 voted for Malia Bouattia, less than 0.005% of the student population. Major figures in the last OUSU referendum on the NUS have expressed the same view, including ex-OUSU President Louis Trup.

There has been a great shift in our relationship with the NUS. What was founded over 90 years ago as a way to unite student voices across the country no longer is unifying, but is deeply divisive, and makes students angry, rather than represented, and this is shown most fully by the disgraceful avoidance of a genuine reply or a genuine apology from the new NUS President, Malia Bouattia, for comments which over 50 JSoc President across the country have condemned as anti-Semitic.

This is surely the time to hold a referendum, when discontentment and disillusionment with the NUS has been its highest in a very long time, and we hope as many OUSU reps as possible will back it when it comes to Council on Wednesday. Whatever your view on whether we should stay affiliated or whether we should leave, such a referendum will spark a much-needed discussion on the NUS and student democracy more widely, which we haven’t had in too long, and which is sorely needed.

A Beginner’s Guide to… The Mechanisms

The Mechanisms are utterly unique. Each of their albums feature sci-fi reimaginings of classic folklore, from Grimm’s fairy tales to Arthurian myth, perfectly capturing the nerdy passion of Oxford at its best. Most of their songs consist of folk

standards, re-written to suit a plotline, making them a sturdy base line from which to work, and the performers sell their roles (of bloodthirsty space pirates with a penchant for storytelling) with arresting conviction. Recorded in 2012, their debut album Once Upon a Time (in Space) tells the story of a brutal interplanetary dictator and the rebellion led against him. It is probably The Mechanisms’ most accessible album. There are rookie errors – the voice acting, for example, is rather weak – but there’s an absolutely mesmerising story at its core, along with some of the band’s catchiest tunes. Their second

album, Ulysses Dies at Dawn, contains an even headier combination of styles and images, this time creating a grim cyberpunk version of Greek mythology. While a bit less accessible, the central image is absolute genius. Their recent EP, Frankenstein, is strong, with a lean and disturbing tale of a rogue AI, even if the underlying composition feels fairly workmanlike. The Mechanisms still play Oxford occasionally (you may remember their appearance at the Bullingdon in January), and are currently

working on a new full-length album. For fans of folklore or folk-music, this is not a band to be missed, and the fact that it’s right on our

Ana and the Other: a split of the self

The other her looked at Ana with wide, quizzical eyes, expecting, Ana thought, to see some shred of greatness there. Ana leaned back against the counter, pressing her palms, still soapy with disinfectant, into the scuffed laminate. The few patrons in the diner were staring. The old man who’d sent his coffee back twice because it was “too cold” now drank the scalding liquid with renewed fervor. He wanted to see how this would play out.

Ana pushed off the counter with the heels of her hands. Careful not to touch the other her, she skirted around the bar stools and strode with forced ease to the other side. She was happy to be behind the counter where no one could see her knees knock. She pushed the rag to the side, mopping up stray bubbles of disinfectant, and slapped the rag over the side of the plastic bucket. She reached into the pocket of her apron and pulled out a pad and pencil. She flipped to a fresh sheet.

“Can I get you anything?” she asked her other self.

The other her shook her head. “No,” she said. “I just wanted to see you.”

She didn’t sound quite like Ana. Her voice had a different pitch – higher, Ana thought – the consequence of different choices. Maybe her mother hadn’t smoked like Ana’s had. Ana had a sudden urge to meet her other mother, something she had not thought about since the second Earth had been discovered, floating listlessly in that faraway section of space.

Ana rubbed her hands on her faded jeans. The cheap ring Scotty had picked up from a pawnshop the day they found out she was pregnant caught on a tear in the seam.

The jeans hadn’t been new for years. Ana had spotted them in a department store when she was 16. She and her only friend Mikaela had crammed into the dressing room to ogle at the way the pants fit her round hips and short legs. Ana’s abuela had always loved the way Ana took after her mother but growing up in the white suburbs Ana had wished she had looked like her dad and sister: pale and skinny like a lollipop stick. Mikaela lent Ana her sweatpants to wear over the jeans. They walked out of the department store, Mikaela in Ana’s Goodwill slacks, while Ana’s armpits wetted with fear.

She was sweating now. Her deodorant stick had broken this morning and she had had to use Scotty’s. She hoped she didn’t smell like a man. The other her smelled like old woman’s soap. Ana wondered if her other self had showered at her abuela’s that morning. The sudden thought that her abuela may be alive on Earth II made Ana’s stomach clench.

“Can I at least get you some coffee?” Ana asked. She was being rude. She didn’t quite understand why.

“Sure,” the other her said. “That would be nice.”

She talked like a white person. Ana grabbed a mug of dubious cleanliness and sat it down in front of the other her. She poured thick, black coffee up to the rim. “Is that a fresh pot?” the old man in the booth asked. The mother at the table by the window gasped at his boldness and turned to stare at her reflection in the dark glass. Outside, cars rushed by in blissful ignorance along the highway.

“No,” Ana said. She sat the pot back on the burner.

“I’ll take a refill anyway,” the man said. Ana stared at him. He was grinning. He was proud of the way he had inserted himself into her private moment. Ana poured coffee into a new cup and stuck it in the microwave. She punched two minutes into the machine.

Across the diner, the mother was watching Ana in the reflection of the window, scolding her child for staring. He was a freckled boy with sandy hair. He had turned himself around in his seat and gaped through the slats in the chair. Ana turned back to her other self.

“So,” Ana said. “What do you want?”

The other her looked down at her untouched coffee. She spread her fingers on the counter. “I don’t know,” she said. “I want… to know you.”

Ana scratched her head. She wanted to know her, too. All the mistakes her other self had or hadn’t made. She wondered what she had done during 7 minutes in Heaven with Jeremy Ekkerd or if she had worn white jeans the day she got her period in tenth grade. She wanted to know who she was when she had the chance to be someone else. Without meaning to, Ana rested her hands on the growing bump under her apron.

Her other self looked up at her and shook her head. “I’m sorry,” she said. “This was a mistake.”

The other her stood up to leave. “That’s $1.99 for the coffee,” Ana blurted.

Ana’s other self stared at her. Maybe they don’t have dollars where she’s from, Ana thought. She began to panic. Maybe everything was different there. Maybe George Washington and his band of merry rebels had never flipped England the bird. Maybe her world dealt in gold still or something completely foreign to Ana.

The other Ana reached into her pocket and pulled out a few crumbled bills. She placed two on the counter. George Washington’s bored, stoic expression stared up at “I’ll get you your change,” Ana said. She pressed a few buttons on the register. The drawer spit open.

“That’s alright,” the other her said. “Thank you for this.” She walked out the door. The chiming of the bell as the door slammed closed brought a hand to the mother’s mouth. The woman clenched her eyes shut and started to shake. Ana rushed around the counter and outside into the parking lot. She looked up at the sky, expecting some sort of spaceship to be hovering over the neon sign announcing their 24/7 open guarantee, but above there was only darkness.

Ana wiped warm rain off of her face and squinted at the cars rushing passed on the highway. She must be then the other her had found the other Scotty somehow.

Ana wiped her hands on her damp, stolen jeans, turned, and with hand on her growing child, re-entered the diner where growing child, re-entered the diner where her life was waiting.

Recipe: Breakfast Bircher Bowl

You can prepare most of this the night before, making it the perfect breakfast to eat on the go in the morning. It’s healthy too, and has a very low GI – which means it’ll keep you going all the way to lunch!

Ingredients (serves 1):

25g oats

100ml milk/almond milk/apple juice

Salt

1 apple

1 tbsp yoghurt

1 tsp honey

Hazelnuts/ walnuts or similar

Raisins

1) Place the oats in a bowl with the liquid and a pinch of salt, cover with clingfilm and leave in the fridge overnight. This lets the oats soften and creates a much nicer texture than using unsoaked oats. You can use whichever type of liquid you prefer – almond milk makes a sweeter bircher, while apple juice gives a fresher taste.

2) In the morning, stir the oats and grate the apple on top.

3) Add the yoghurt and honey, and mix it all together. Chop up the hazelnuts and scatter on top with the raisins too.

It’s really easy to adapt this recipe to in- clude different types of nuts, seeds or fruit; just use the oats, milk, apple and yoghurt as a base and then experiment away! Enjoy!

Best cafés for studying in Oxford

- Pret a Manger: Usefully situated at the top of Cornmarket, this is an ideal place to work. There are a few seating areas to choose from, all open plan and split up by overhead beams (upstairs is best for working). It gets busy in the afternoon, but first thing in the morning it’s quiet and you can hear the the surprisingly good acoustic playlist. Plus the cookies are warm and you might even be able to grab a fresh croissant…

- The Handlebar Cafe and Kitchen: a fairly new café above a bike shop on St Michael’s which serves an amazing all-day brunch – the best kind of revision fuel. From the coffees to the bikes hanging from the ceiling it’s all very pretty and instagram-able, albeit at the more pricey end of the scale. The staff are friendly and it’s become so popular to work here that they’ve even intro- duced “study zones” during peak times.

- Waterstones Café: on the 2nd floor of Waterstones there is a café which overlooks the edge of Broad Street. It’s light and airy with floor-length windows, and there’s a mix of low armchairs, bench seats and classic tables. The coffee is good, and this is one of those places where you never feel pushed to order another to stay longer.

- Queen’s Lane Coffee House: this is one of the oldest coffee houses in Oxford, (alongside the Grand Cafe on the opposite side of the road) but isn’t stuffy or snooty and happens to serve paninis that rival even Taylors. There are two rooms and loads of tables; it’s not that special inside but the service is great. It has an extensive drinks menu too, so whether you’re a vanilla chai latte or simple filter coffee kind of person it will satisfy your essay cravings.

-

Brew: this tiny café on North Parade (just on the left from the Banbury Road side) has only a handful of tables and serves quality coffee in little teacups. It provides an escape from town without being in the library, and also brings you to the cute independent shops and sandwich bars close by. Bear in mind how small it is though – it’s not the place to spread out pages of notes and several books.

MOOCs: the future since 2012

Online courses have been the future of education since 2012, when the three behemoths of the digital degree – Coursera, Udacity and edX – were founded. We are now in 2016, and by my estimation, that future is no closer than it was four years ago. The unfortunate reality is that brick-and-mortar institutions, especially ones as caught up in their own history as Oxford University, cannot be made “redundant,” as Brockliss argues, by the Internet.

There are two reasons for this. First, that the university experience is just that: an experience. Massive open online courses, or MOOCs as they’re known, cannot be compared. There is an insurmountable difference between the three to four-year undergraduate degree – where one is surrounded by peers and liberated from the constraints imposed the entirety of one’s life hitherto – and the process of completing online quizzes and homework at a sterile computer screen.

Second, an institution like Oxford, steeped in a thousand years of history, tradition and privilege attracts applicants and professors for those very reasons, not only the superior quality of its existing programmes. For the same reason that alumni donate small (and not-so-small) fortunes to American universities, school students apply to Oxbridge: the brand.

Oxford would be remiss if it did not start playing catch-up in terms of providing online courses. (Harvard, MIT, Stanford and dozens of others already do.) And the digital degree has the potential to be an equalising force in the education market in the coming ten, twenty years. But it might also further stratify, as the brands of the Ivy League and Oxbridge stand firm whilst others begin to weaken.

NUS conference debates Holocaust commemoration

The annual NUS conference began with controversy over the leading presidential candidate and ended with calls for Oxford to disaffiliate from the national union after that candidate was elected. In the meantime, the event dealt with issues ranging from climate change to Yik Yak’s role on campuses.

Perhaps the most widely reported event of the conference, held in Brighton, was when Chester University representative Darta Kaleja argued against commemorating the Holocaust on the grounds that it would ignore other atrocities.

“I am against the NUS ignoring and forgetting other mass genocides and prioritising others,” Kaleja said. “It suggests some lives are more important than others. When during my education was a I taught about the genocides in Tibet or Rwanda? It is important to commemorate all of them.”

This was picked up by national and university media sources; though, it was also often taken out of context to imply Kaleja did not want to commemorate the Holocaust at all, rather than wanting it to be remembered with other atrocities.

In the end, the calls for commemoration of the Holocaust passed along with the rest of the anti-semitism motion proposed by Oxford NUS delegates Oh Well, Alright Then. The Oxford representatives also proposed and passed a motion for the NUS to focus on mental health and made speeches throughout the conference, as well as running a popular live Twitter feed of the event.

Earlier in the conference, members voted to move to ban Yik Yak and other anonymous social media platforms for being “not nice.” They also debated lobbying to ban legal highs and denied the movement for One Member, One Vote soundly, keeping the power centre of the NUS relatively small, which some derided as something that will “do wonders for the student engagement that they already didn’t have.”