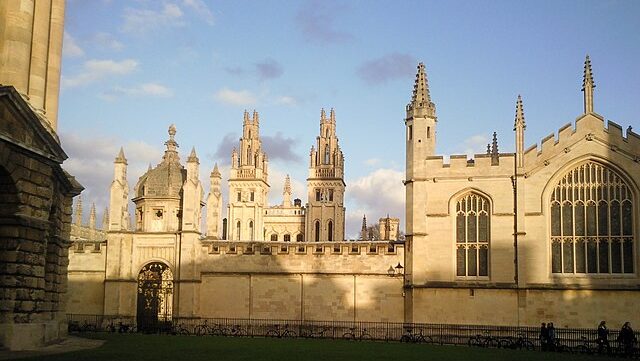

A panel discussion on activism took place at the Sheldonian Theatre last Wednesday as part of the University of Oxford’s Sheldonian Series, prompting debate on the effectiveness, ethics, and democratic role of activism.

The event, titled ‘The Power of Activism’, formed part of the series’ Hilary term focus on the theme of ‘Power’ and was moderated by Dr Julius Grower, Associate Professor of Law at Oxford. Panellists included Shermar Pryce, the Oxford University Student Union (OUSU) President (Communities and Common Rooms); Professor Federica Genovese, Professor of Political Science and International Relations; Munira Mirza, Chief Executive of Civic Future; and climate justice activist Dominique Palmer. Baroness Shami Chakrabarti CBE contributed via pre-recorded remarks.

Opening the evening, Vice-Chancellor Professor Irene Tracey said: “In our world, there is no shortage of issues to be passionate about”, emphasising the relevance of activism in contemporary political life.

The first audience question asked panellists to provide examples of where activism had been successful. Pryce referred to the work of Fair Share during the COVID-19 pandemic, while Genovese highlighted global fossil fuel divestment, stating that “16,000 institutions” had stopped investing in fossil fuels, resulting in losses of “about $40 trillion”. Palmer cited the Stop Rosebank campaign, while Mirza pointed to recent farmers’ protests, including demonstrations in Oxford.

Discussion then turned to examples of activism perceived as unsuccessful. Pryce cited the 2003 Stop the War protests against the Iraq War, arguing that they failed because they did not “change the incentives of institutions”. Palmer questioned whether failure in activism could be clearly defined, while Mirza reflected on her early involvement in activism and argued that some forms of disruptive climate activism risk alienating the public. Genovese added that measuring success is difficult because it is often unclear which outcomes most people want.

Baroness Chakrabarti offered a broad definition of activism as “any form of political expression”, while noting that the term can sometimes carry negative connotations. Mirza stressed that activism is not always progressive or left-wing, citing the British National Party as an example, and argued that it is important to distinguish between activism grounded in persuasion and activism grounded in coercion.

An audience question later raised whether disruptive protests could be justified, citing farmers’ demonstrations. Mirza responded that such protests had been organised and permitted by the police, while Pryce noted that movements such as the suffragettes were also criticised in their time.

Genovese shifted the discussion to activism in democratic versus non-democratic contexts, arguing that “democracies work best with incremental changes” and citing Brexit as an example of a rapid political shift that democratic systems struggled to absorb.

Toward the end of the event, an audience member interrupted to ask why Palestine Action had not been discussed, particularly in light of its designation as a terrorist organisation. The moderator stated that the question would be returned to later; however, although two further audience questions were taken, the issue was not subsequently addressed by the panellists.

Despite this, the University described the event as “a stimulating evening of discussion” with an engaged audience. Dr Grower described the panel as “a brilliant demonstration of what Oxford does best”, emphasising the role of universities in facilitating debate on contentious issues.

The Sheldonian Series is open to the public and aims to promote freedom of speech and inclusive inquiry. The final event of the academic year, focusing on the ‘Power of Satire’, will take place in Trinity term.