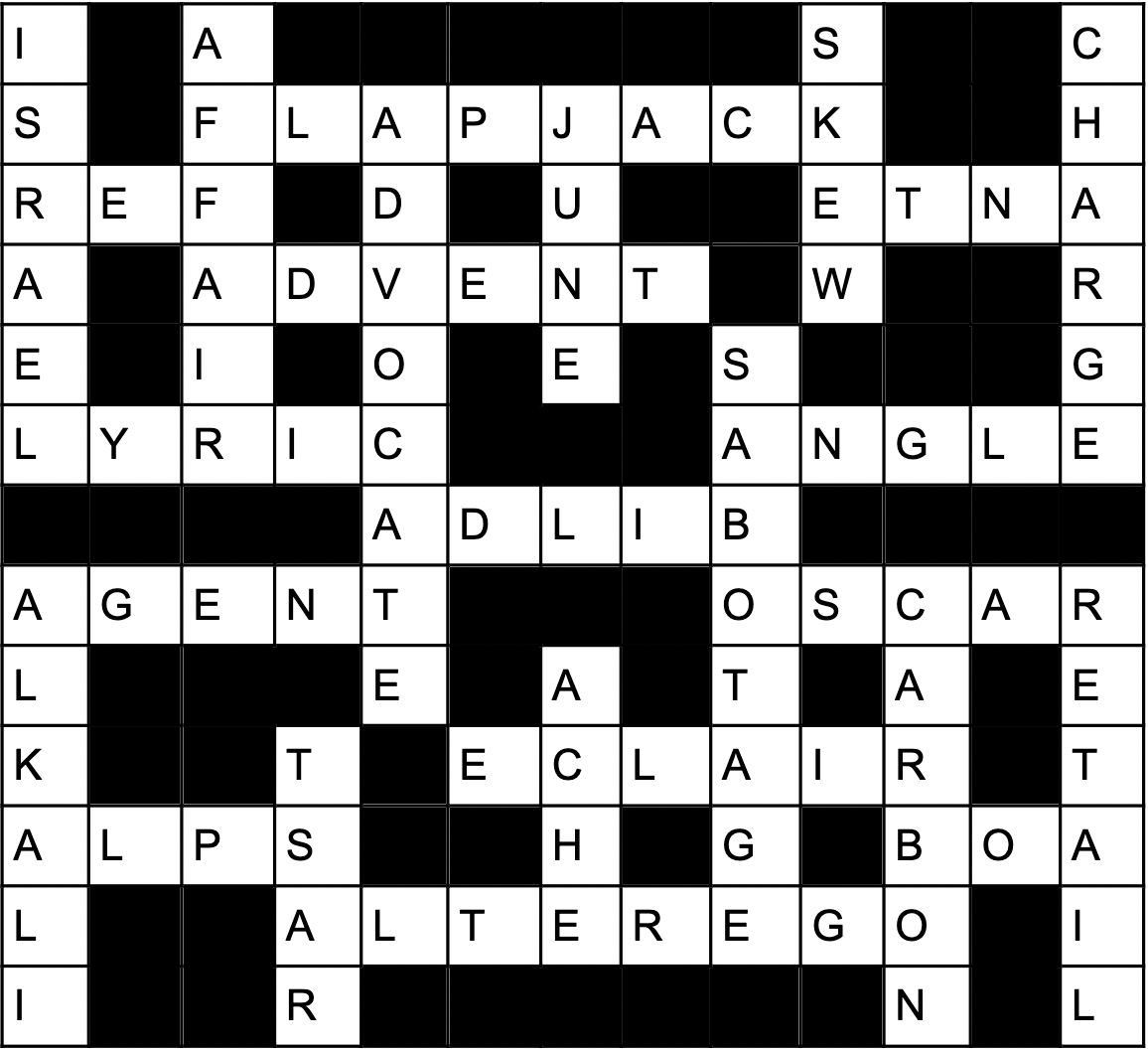

Crossword:

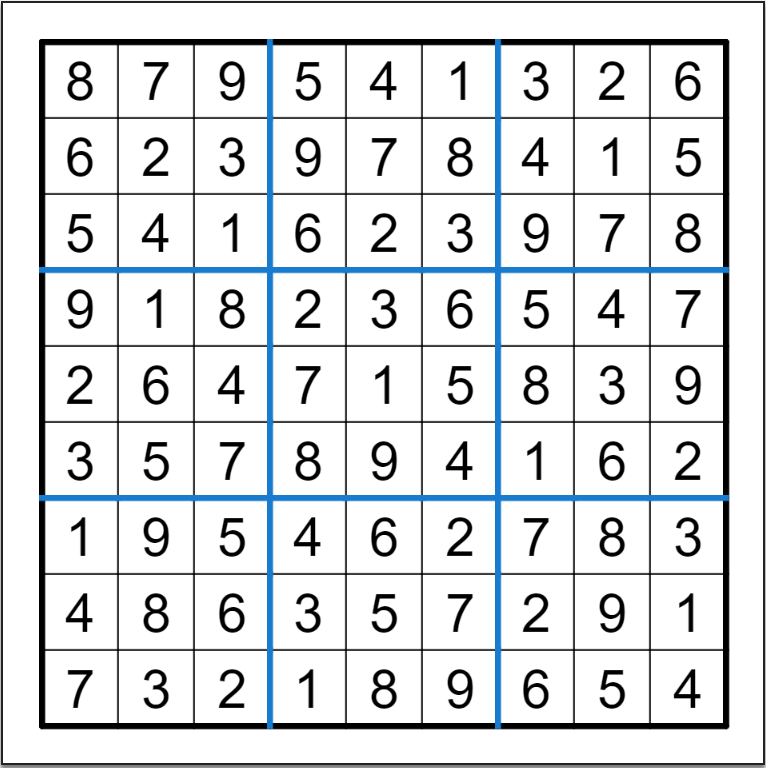

Sudoku:

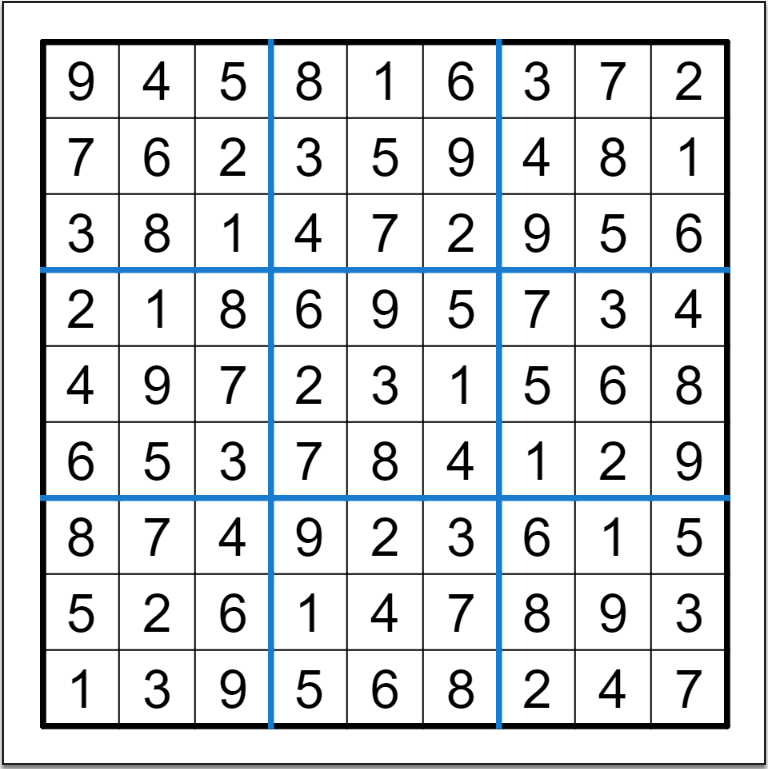

Oxdoku:

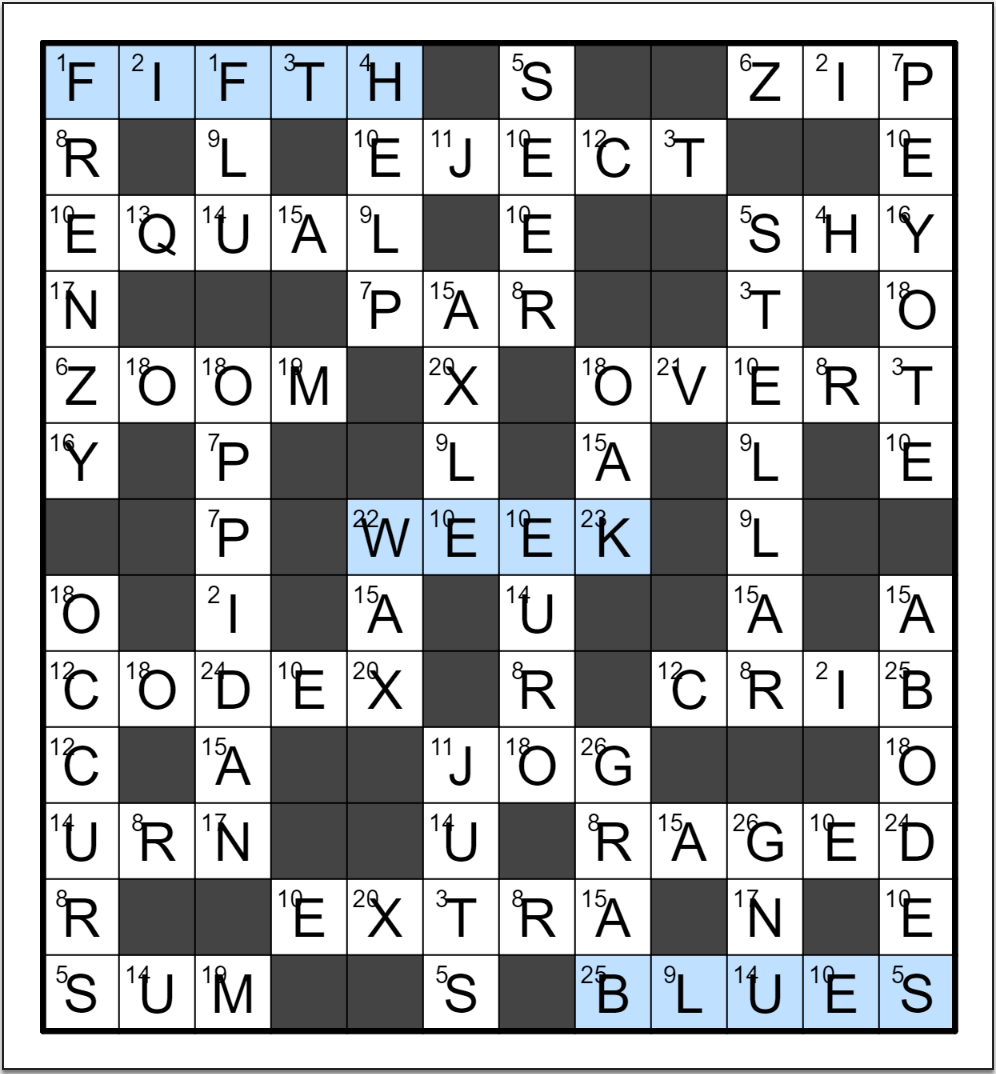

Codeword:

The Former Australian Prime Minister, Scott Morrison, will give a talk at the Oxford Union this Thursday at 5pm.

The talk is part of a larger UK trip which included visits to think tanks and other speaker events. The AUKUS submarine deal is another focus of this trip. Morrison told The Financial Review that “these events will provide further opportunities to promote AUKUS in the UK” and emphasised the close links between Australia and the UK.

Morrison was PM from 2018-2022. His time in power was characterised by major flooding and forest fires in Australia, the COVID-19 pandemic and his support for Ukraine.

Outgoing Union President, Matthew Dick, told Cherwell “I am really excited to be bringing the members another brilliant opportunity to hear from and question a former leader of a commonwealth state. It’s a brilliant way to end the term”. The talk will take place in the Union chamber at 5pm this Thursday 15 June.

Breeches and brotherhood … the secret world of freemasonry is something largely obscure and unknown to the uninitiated. After spending some time among the brethren of Apollo University Lodge, this is what Cherwell found.

What is Freemasonry and what is Apollo University Lodge?

Freemasonry is one of the world’s largest non-religious, non-political, and charitable organisations. Its roots can be traced back to medieval stonemasons and Cathedral builders. It is founded upon the three principles of “Brotherly love”, “Relief” and “Truth”. Today, there are approximately 250,000 members under the United Grand Lodge of England and 6 million around the world.

Apollo University Lodge – a “Lodge” being a local group of freemasons – represents the freemasons who have matriculated at the University of Oxford. It held its first meeting on 10th February 1819. Now, meetings are held six times a year, with two ceremonies typically performed at each meeting.

At Apollo, the traditional attire of white or black tie is commonly worn at meetings and dinners. At the dinners, charitable collections are made in support of University and local charities. Additionally, Apollo funds seven grants of £1,100 each which are then awarded by the University.

Like any Masonic Lodge, the process for becoming a full member at Apollo University Lodge incorporates three distinct “degrees” relating to the values of Freemasonry. Symbolically, these degrees, namely Entered Apprentice, Fellowcraft, and Master Mason encompass the development of the three stages of life: youth, manhood, and maturity.

History

“A medal be cast to be worn by each member suspended by a piece of blue riband, and be stamped on one side with an Apollo,” ran the resolution of a meeting of freemasons in Brasenose College in 1818, with a view to founding Apollo University Lodge.

From the outset, charity work was a constituent of lodge life. Records show an agreement of the first Apollo members to give a guinea annually to “the Charity for Female Children and the Institution for Clothing, as well as the Sons of Ingredient and Deceased Masons.”

It is possible that members of Apollo were mainly concerned with activities other than charitable aid. The Lodge records show that a short lecture was given to members of the Apollo by the elder statesman of Oxford masonry concerning “behaviour outside the Lodge” and “warning the Brethren to be particularly cautious in all their conduct.”

Conflict between Apollo and the Grand Lodge was not uncommon in the early years. The Grand Secretaries of English Freemasonry took issue with the too rapid initiation of members into Apollo, which they considered to contravene the Masonic constitution. Apollo was forced to “petition the Grand Lodge for their forgiveness”, expressing their “regret at having, as inexperienced freemasons, acted improperly”, further pleading that “the Book of Constitutions was being revised and therefore they had no copy”, when the Lodge had been constituted. Eventually, Apollo petitioned the Grand Master to permit the initiation of “gentlemen under 21 years of age”, promising that those proposed for initiation would be selected as eligible according to their “character and rank”.

The Lodge grew steadily through the 19th century and enjoyed a period of social extravagance in the latter part of the 19th century. Royal affiliations were strong, with the Lodge organising a ball in celebration of the wedding of Edward Prince of Wales in 1863. Queen Victoria’s youngest son Leopold was installed as master of Apollo in 1876.

The records suggest that the 20th Century and the war years were more testing for Apollo. Aside from an influx of ex-servicemen after the first world war, annual initiations declined to on average below 20. The government requested that the Lodge’s meetings be suspended following the outbreak of war in 1939. Whilst Lodge activity resumed in 1945, these years were more mundane than the pre-war heyday.

Joining Apollo

In Cherwell’s conversations with Apollo members, we were intrigued to uncover the variety of routes that led people to join the organisation. Whilst the secretive nature is intriguing for some, others are drawn in because they have close friends who are part of Apollo, or even have freemasonry running in the family.

Chris Noon, Apollo University Lodge Secretary, told Cherwell about his path: “I knew about freemasonry because my dad joined when I was about twelve. He didn’t tell me much about it at the time, but he took my family to a couple of open guest dinners, and we met some really great people. I had thought I’d join his Lodge when I turned 21, but then I had a chance encounter with someone who turned out to be a member of Apollo, who told me that I could join it younger because it’s a University Lodge (I was 19 at the time). I asked my dad whether he thought I should do this, or wait to join his Lodge, and he said he thought I’d get more out of it if I joined at University, where there would be more young people (and people who lived near me). And he was right!”

Currently, the qualifying age to join freemasonry is 18. Apollo’s current membership is around 300 and is made up of roughly 100 members of the University and its departments, as well as alumni.

Like most lodges, Apollo does not recruit its members. Instead, it operates through a three-tiered application process. This begins with those who are interested in contacting the Lodge through its website. Once someone has got in touch, a two-stage interview process follows; the first being an informal chat with one of the Officers of Apollo University Lodge, with no preparation or detailed knowledge of freemasonry being expected. The second interview is more formal, and candidates are expected to have dived into Freemasonry and reflected on the initial meeting.

The current Master, Alexander Yen, gave Cherwell insight into the specific questions asked in the interviews. In essence, interviewers want to know what the appeal of freemasonry is to the applicants. Yen told Cherwell: “We ask for an understanding of the three grand principles, what brotherly love means, what relief means, what truth means. Often, we try and ask them to link to personal experience; is there something that in their life that they have done? Have they been involved in charity before?”

Yen highlighted that the Lodge takes into account the different personal circumstances of prospective members. He stressed that the interviewers are keen to expose any of the applicant’s political ambitions. This is particularly crucial as discussion of politics and religion is forbidden among members. He said that an applicant might be asked: “Are you planning to be politically involved, and likely to cause political controversies for the Lodge?” Yen added that they “try and ensure people who are politically involved join after any ambitions are extinguished.”

It is a condition of membership that an applicant has belief in a Supreme Being or “Grand Architect of the Universe”. Crucially, this does not mean a subscription to religion.

Whilst a freemason’s commitment to brotherly loyalty may appear to have the potential for scheming and corruption in professional spheres, Noon emphasised that applicants should not wish to join Apollo University Lodge as a networking society: “Anyone who is thinking about joining to make business connections would be told that this isn’t what Freemasonry is about and that there are other societies one could join for this purpose, like Rotary… or, well, LinkedIn!”

Data suggests that the total number of initiates in 2023 will be roughly between 20-25. Over the last decade (2012 – 2022), Apollo University Lodge averaged about 19 Initiates a year. Figures include the pandemic but exclude members initiated at other lodges.

Graph showing annual intake of Apollo University Lodge between 2012-2022

Image problems

If any at all, the image Freemasonry has come to cultivate is a slightly blurry, non-transparent one. Secretive, male-only Oxford dining societies tend to court bad press. The perception that Oxford freemasonry represents something elitist and outdated came to the forefront in Michaelmas 2022. Timetabling issues at the Oxford Union led to Freemason drinks clashing with a state school-oriented access social event. Cherwell reported that the Freemasons’ “appearance in white tie caused particular upset” among attendees at the Union event.

Chris Noon suggested that perceptions of Freemasonry as exclusive and elitist were misguided. He himself attended a state school and felt that it was patronising to suggest that aspects of Masonic convention such as a dress code consisting of white tie and breeches might alienate those from lower socio-economic backgrounds. When asked about the intake for this year, he admitted that the Lodge does not collect demographic data, but said that “these people are of a number of different nationalities and socioeconomic backgrounds.”

It is notable that accusations pertaining to the potentially exclusive and collusive nature of freemasonry have courted press attention beyond Oxford in recent years. In 2017, the outgoing chair of the Policing Federation Steven White alleged that progressive policing reforms intending to support women and officers from black and ethnic minority backgrounds were being blocked by freemasons within the police.

David Staples, erstwhile Chief Executive of the United Grand Lodge of England (UGLE), responded in a letter to the press saying that “the idea that reform within the Police Federation or anywhere else is being thwarted by an organised body of freemasons is laughable”, and underlining the “organisational values of integrity and service to the community” shared by police officers and freemasons.

When interviewed, some members of Apollo University Lodge expressed irritation at what they viewed as unfair publicity in a press that largely disregards their charity work. One member, who was initiated into Apollo in 1968 and has since been active in various London Masonic lodges, mentioned the 210-foot ladder which freemason donations had funded for the London Fire Brigade, as well as the £3 million pledge made to the London Air Ambulance charity to help towards a fleet of two new helicopters costing £15 million in total.

The member complained that there was little news coverage of these activities. When asked about the secretive Masonic image, he referred to the war years, suggesting that Freemasonry “became more sensitive to what people thought of it because of Nazi persecution.” There is little doubt that Freemasonry became the target of Nazi propaganda linking Jews and Freemasons, particularly before the war.

Others have suggested that secrecy is an integral part of Freemasonry. Guardian journalist Iain Cobain wrote in 2018: “Freemasonry could not abandon its last vestiges of secrecy, even if individual masons wished to, because it is key to the future of the brotherhood. Men continue to join in order to discover what is being hidden from them.”

Moving Forward

Staples, who was Chief Executive Officer of UGLE for five years. He told Cherwell that the position of CEO was created with him at the helm as part of a broader effort to modernise and open up the Masonic community.

In 2018, the Guardian reported that Staples said that the perception of freemasonry as a secretive organisation is changing. He added: “We have a greater resolve to put forward a case – and it is a positive argument – to highlight that we are driven by integrity, by a desire to help those less fortunate than us, and to stem the flow of negative perceptions which has unfairly dominated public perception.”

Notable recent developments include the 2007 establishment of the Universities Scheme. This programme intends to broaden the appeal of freemasonry to a younger audience beyond Oxbridge. Noon said: “The Universities’ Scheme was set up to give students at more universities the opportunity to learn about and join freemasonry while they are still students.” He noted the success and popularity of Apollo and the Isaac Newton Lodge at Cambridge, suggesting that the lower age of 18 at which one can become initiated into University lodges “gives it a chance to become a part of your life before you have career or family commitments.”

Whilst Apollo University Lodge remains a lodge exclusively for men, other lodges accept women. This follows in a tradition of women’s freemasonry beginning with the exclusion of men from the Honourable Fraternity of Ancient Masonry in the early 1920s. In Cherwell’s discussions with Apollo members, there were whisperings about the potential for an Oxford University women’s lodge. In the meantime, Noon told Cherwell that women who enquire about Apollo in Oxford are referred to the two women’s grand lodges in England, Freemasonry for Women and Order of Women Freemasons. Indeed, Noon was quick to reassure that “there are a few of these a year, too!”

Every time someone tells me “Harry Potter is for children”, I wonder if those people know anything about what it is like to have their own opinion and not blindly follow the crowds of narrow-minded people. I am 25 years old, and I have reread the Harry Potter books 10 times, but in this review I want to introduce you to something truly special.

About a year ago, I came across a book titled Harry Potter as Therapy and it felt like someone had finally put into words everything my not-so-eloquent self had been trying to tell the world. The book is written by a psychiatrist/ psychotherapist, Dr Iurii Wagin, with 35+ years of practice in psychotherapy, who shares the anecdotal evidence about the nature of the characters and the rationale behind their decisions, all backed up by professional experience.

I always knew my affection for the book series was not just based on dragons and magic (though I keep imagining how much easier getting to the furthest Ox department would be if I could just apparate). Every time I read the books and watch the films I uncover the truth about the human psychology, especially given the fact that so many things happening in the books reflect our every day lives. We all are familiar with things like resisting annoying family members, having to tolerate the attitude of rough teachers, the sweet joy of having friends, and even dealing with the evil on an everyday basis (don’t you tell me having to do 2 full exams in a single day is not pure evil). Harry Potter as Therapy has opened my eyes to the importance of those things in the Potter books, but also to how much life wisdom and accurate portrayal of psychological nuances is hidden in the series.

What strikes me most is how unexpectedly deep the book is. To be frank, I did not expect much from it as I was aware of the books of this kind that mainly analyzed the events and attempted to find the metaphors about our imperfect world (not so hard to do given the news we hear every day). However, this book was different. It did not so much analyze Harry Potter; it explained it from the point of modern psychotherapy. Going all the way from such superficial topics as the friendship of the main trio and why Voldemort is a jerk (which, clearly, needs no reiteration) to tapping into objectification, depression, fear of death, and why the picture-perfect Hermione actually chose the local simpleton Ron instead of the great Harry Potter (this part blew my mind with how simple and brilliant it was).

Another feature that makes the book stand out is the abundance of actual anecdotal evidence from the Dr Iurii Wagin’s professional practice. How often do you talk to someone who has seen the very worst of the humankind’s mental struggles? Every single chapter sheds light on the real life cases that the Doctor had to deal with, spiced with how outstandingly wittily they are written up. Doctor talks about catatonia, hiding pregnancies, marriages, the philosophy of hedonism, the Nazi, and homosexuality (the Oxford comma is vital here), and many more life peculiarities. And yes, all of those are related to the Harry Potter series.

As a linguist, I also found so much joy in word play, comparisons and metaphors that just hit you differently. Let me finish expressing my utter appreciation of the Harry Potter as Therapy book by including a couple of quotes:

“A parent’s love is like radiation. In small doses, it energizes. But large doses produce mutants.”

“Life reminds us once again that courage isn’t the absence of fear, but the ability to keep going even when you’re very afraid. If men learn this lesson, women will cherish and embrace us rather than books about Harry Potter.“

“To this day, many people are still sincerely surprised that children all over the world avidly read Harry Potter. I think it’s because it teaches children what they can’t necessarily learn from us. That you shouldn’t eat shit, no matter what reward is offered for it. That lives do not have an absolute value, but rather a relative one. And that we must always fight to the end.”

In case you are not a big Harry Potter person, I would still encourage you to read the book. the book provides practical life advice and may help you look at different life situations from a different angle. I was able to discover certain truths that happened to be the result of imposed values rather than my own thinking, and to get rid of them. Just like a cup of nice warm tea in the evening, the book leaves a calming aftertaste and teaches you not to be afraid to be yourself and to embrace your very own experiences. And for that, I am grateful.

Originally, the book is written in Russian as the author has written all of his books in his first language, though he permanently lives in France. Fortunately, recently the author revealed that “Harry Potter as Therapy” will be out very soon in English this summer, and I couldn’t help sharing my appreciation with the Oxford audience!

Follow the author’s Twitter, @DrWagin (https://twitter.com/DrWagin), or his Instagram (run in Russian) @doctorvagin, and look out for the official launch of the e-book on Amazon! Do not miss on your chance to dive into the world of character psychology, and to save some money on therapy for the beautiful summer strawberries (;

When one hears that a play is going to heavily feature social media and pop culture references, one instinctively prepares to cringe. In By Proxy, however, writer and director Imee Marriott has skillfully crafted a show that feels authentically in tune with modern life. This one-act, hour-long firecracker of a piece opens with a hilariously ice-breaking scene, introducing its main characters, the teenagers Kit (Edie Critchley) and Jo (Maisie Lambert). They play Just Dance and banter over such far-ranging topics as Nelson Mandela teabags, Jo’s new love interest, and Pedro Pascal, setting the tone for the fast-paced, convincingly-acted dialogue that will characterise the play to come.

By Proxy follows Kit and Jo as they progress from this pair of high school best friends into young women, going to university and making decisions for themselves as their lives drift apart. Most impressive is the writing’s clever development, showing how Kit and Jo’s relationship dynamic switches ominously as Kit comes into her own at university and Jo seems to just keep slipping. It is equal parts devastating and fascinating to watch their intimacy gradually wane, as the pair begin to communicate more and more indirectly via phone calls, voice notes and eventually a radio broadcast — hence the title, By Proxy.

This play really utilises technical effects to incorporate social media into the story, the sound design and projections (Will Wilson) and lighting (Maxi Grindley) pull together to show us the girls’ texts, BeReals, and Instagram accounts in ways that effectively supplement our understanding of the characters and their world. For all the technical brilliance of the show, the most hard-hitting scene is a monologue in which Jo records a voice note to Kit: stripped back, vulnerable, and bursting with emotional truth, this is a stand-out achievement by Lambert.

Critchley and Lambert’s chemistry furthermore captivates as they manage to deftly capture the nuances of Kit and Jo’s friendship throughout their performance: their attraction, resentment, dependence, love, and disgust towards each other all twisting together deliciously. They bounce off each other so well, in fact, that in the one scene we see another character on stage, Marcia (Susie Weidmann), her character seems slightly cartoonish in her characterisation and relative lack of depth. Marcia is, however, crucial to the storyline, highlighting another of the play’s virtues: it is a rare student play that is both artistically convincing and boasts a plot. Not much can be said of this plot without ruining the writing’s delicately slow reveal of the truth, but it is worth checking the play’s trigger warnings before attending, and preparing yourself for heartbreak.

By Proxy is shocking, morally complicated, and will have you frustrated, yet empathetic towards both Kit and Jo. It is also hysterically funny, with witty dialogue and inside jokes that will appeal to the Oxford student. By Proxy is a brilliant balancing act that engages at every turn.

There are few environments more inhospitable to human personality than the interior of a Boeing 747. ‘Ah, 23B! Home sweet home’: the words of a madman. A friend of mine has decorated their room in Oxford with some posters of Hokusai’s The Great Wave, Van Gogh’s Starry Night and The Godfather; on an EasyJet flight from Heathrow to Barcelona, the closest equivalent to such bold self-representation is removing your shoes or letting your seat back, only to discover with horror that this brings you several inches closer to the toddler who’s going to give you tinnitus for the next two hours.

Cleopatra Coleman’s decision to set her new play, Window Seat, in an aeroplane, thus comes as something of a surprise. From the characters in a drama we hope for something distinct and individual, but on most flights I have found myself too enraptured by ‘tantrum in G Minor’ to give the idiosyncrasies of my personality, let alone anyone else’s, much thought. Yet in Coleman’s case this choice of setting is a stroke of genius, because it is precisely the conflict between character and convention (person and passenger) with which Window Seat deals.

The plot is structured around a conversation between middle-aged mother Trix (Marianne Nossair) and her adolescent daughter Lois (Avanthika Balaji), recently returned from her second term at university. These two, at first glance, couldn’t look more different. For Trix, think Dolores Umbridge’s philosophy applied to Kate Bush’s wardrobe: florid and quirky, but governed by an urbanity that always keeps the handbag tucked neatly under the seat. Lois’ altogether more androgynous appearance, her boyish clothes and short hair—a detail her mother fussily laments—contrasts starkly with this. Even the characters’ movements, directed by Lydia Free, point to the subtle differences between them: whilst mother applies hand lotion with fastidious elegance, daughter carelessly kicks her trainers off and rests her feet on the seat.

What generates the drama in Window Seat is the collision between this apparent difference and an underlying similarity between the two characters. Lois and her mother’s various discussions repeatedly lead back to the question of whether Trix’s behaviour towards her daughter is motivated by nostalgia for a life she herself could have had, but did not live. ‘An interior designer and an artist could not be more different’, Trix assures us, but as the play progresses it becomes increasingly evident that she is living certain aspects of her life vicariously through her daughter. Trix admits how ‘Freudian’ it is that she named her daughter after an old unrequited lover, and this makes it only natural to wonder whether Lois is just a symptom of her mother’s unfulfillment. Trix wants to be a passenger in her daughter’s future, but only if that future is a passenger in Trix’s own fantasy of the life she never led.. And the audience is a kind of passenger too, patiently attending to action they are not part of.

Passengers, moreover, are passive. I’ve always liked to think that the louder the toddlers cry, the faster the plane goes, but alas, we don’t live in Monsters Inc. Trix is waiting for her daughter to do what she always wished she had; Lois is waiting for her mother to give her permission to do those things; the audience is waiting for the stalemate to be broken; and everyone is waiting for the plane to take off. This aesthetic of delay does draw the audience into greater sympathy with the characters, but it also risks reducing the play to a series of swings between action and reaction. Trix can only show her concern for her daughter’s wellbeing when Lois brings up the topic of music festivals; Lois can only criticise her mother’s obstinacy when Trix expresses her disapproval for her son’s partner. Dialogue is necessarily reactive to some degree, and in fact Lois’ horrified responses to her mother’s outrageous comments produce some of the funniest moments in Window Seat (which is, I should stress, hilarious). ‘I became the Jeremy Clarkson of tits’, is brilliant enough on its own, but Nossair’s unapologetically nonchalant delivery, not uncoloured by a hint of mischief and followed by the helpless squirming of Balaji, makes it practically unforgettable. However, it does occasionally feel that the characters are merely waiting for their cues from one another rather than engaging in a natural conversation.

Nonetheless, the play is a joy to watch. Coleman always provides just enough detail in the dialogue to allow the audience to follow what is happening without making the relationship between the two characters seem overlaboured or mechanistic. Tilly Dyson’s sound design interjects the performance with announcements that provide comic relief—geese sunbathing on the runway—whilst also providing an element of direction that gently draws the play towards its conclusion. Gently, because we are not to expect any sudden climaxes or dilemmas.

The structure of the dialogue is aggregative as well as reactive: more and more topics are slowly incorporated to flesh out the emotional history of mother and daughter without us really registering that this is happening. There are no passionate declarations of devotion nor violent outbursts of anger. The word ‘love’ is spoken only once, yet the familial love between Trix and Lois is not cast into doubt for even a moment. It emanates from the cheeky intimacy of the humour, the warmth of the reminiscences, the fervour with which Balaji raves about feminist literature and her radio show and the quiet tenderness with which Nossair encourages her.

Peter Kessler complains of Window Seat that ‘these characters’ vehicle just doesn’t quite take flight’, but I think that it is this which makes the play simmer so powerfully in its final third. This power is that of potential rather than attainment, like knowing the seatbelt sign will turn off but not knowing quite when. No, we never learn whether Lois goes to the festival, or if her brother becomes reintegrated in the family. But the energy the play generates towards its close is such that the audience is bestowed with the freedom to imagine all of these things, and that is no bad thing.

In the President’s Garden of Magdalen College, the winding path to my seat brought me past the cast already in character and costume, putting the audience straight into the fantastical world of Shakespeare’s creation. A Midsummer Night’s Dream makes a rather fitting choice for a garden play, given that the majority of it takes place in the fairy-world of woods and glens; the well-designed soundscape only added to this, I couldn’t tell if the birdsong was recorded or emanating the trees around me. The immersive feel continued throughout, and the space of the garden was used creatively. The role of the fairies in this production was one of the best ways this came through, as they often appeared from an unexpected angle, part of the garden themselves. Puck (Caitlin McAnespy) was a highlight, both in the spectacular costume and the fluid movements of the shadowy character.

Without a doubt, the audience-favourite moment had to have been the love scene between Oberon (Aravind Ravi) and Bottom (Tom Vallely) – this production followed in the footsteps of the Bridge Theatre’s 2019 decision to reverse the typical power balance of the fairy monarchs, speaking interestingly to the themes of sexuality, gender and power that permeate the play. When ‘I Put A Spell On You’ began to play and the fairies began their burlesque dance, the garden was in hysterics (or at least my row of the audience was). Gloriously camp and brilliantly choreographed, the – um – climax of the scene (complete with a confetti cannon) was a strong act-closing moment.

Returning after the interval, it felt suddenly darker, with the impressive lighting bathing the performance space in pink. Whilst the fairies dominated the first part, the physical staging of the four lovers’ quarrel brought their story to the foreground later on, bringing the iconic scenes of confusion and ultimate reconciliation (it is a comedy after all, which was never forgotten in this production). Again, the interaction with the audience when Theseus et al joined the picnic blanket seating area for ‘Pyramus and Thisbe’ felt immersive and heightened that moment of metatheatricality.

Yes, it may have reminded me of other recent versions of this play. However, it is a Shakespeare play, so sometimes doing what we know well is the best strategy, which was certainly achieved here. All in all, a dream-like and wonderful way to spend the ‘three hours between our after-supper and bedtime’, in the words of Theseus himself.

Brasenose College JCR has voted to disaffiliate from the Oxford Student Union (SU), and by extension from the National Union of Students (NUS).

In an email seen by Cherwell, the Brasenose JCR Secretary told students that “[f]ollowing the referenda a couple of weeks ago, I am now able to announce that Brasenose JCR has voted to disaffiliate from both Oxford SU and the National Union of Students”. The email continued, reassuring students that “the JCR’s disaffiliation from both organisations will not affect your individual rights to interact with the SU or the NUS, nor to make use of their services”.

While Brasenose College JCR is not directly affiliated with the NUS, the motion for disaffiliation that was passed was titled “Disaffiliation from the SU and the NUS”. The motion noted that “[a]ffiliation with the NUS costs the SU, and therefore the collective student body, over £20,000 a year”, and added that the JCR “should not stand for the unaccountability of the NUS regarding its structural failure to efficiently combat antisemitism”, referencing Rebecca Tuck KC’s independent report into antisemitism within the NUS. Regarding the SU, the motion said it was “structurally unsound … the Sabbatical Trustees are ineffective, unaccountable … and at times uncooperative, whilst being paid around £25k”.

The Brasenose JCR Committee told Cherwell that during the meeting to discuss affiliation it had to be explained what the SU actually does, which they think “clearly shows that the SU is neither active nor vocal enough to garner the attention of our students”. The Committee said that the “absence of a working relationship” between the JCR and the SU meant members of the JCR Committee “have had to resort to consulting with the Vice Chancellor directly, which negates the founding purpose of the SU as an intermediary”. The Committee also criticised the SU’s decision to retract a statement against Kathleen Stock, claiming that “the SU leadership does not do enough to defend the voices of the student body, and those of vulnerable minority groups in particular”. The Committee concluded: “The SU does not work for our students. As such, we see no reason to remain affiliated.”

Joel Bassett, Brasenose JCR Secretary, emphasised to Cherwell that the referendum had been held purely because the JCR is bound to propose a motion considering its affiliation every Trinity Term. However, Bassett added that he “personally put forward a case in favour of disaffiliating from both organisations”. He thought the SU “has not made enough of an effort to effect change at a university level, and has not made an effort to work with our JCR”, and also cited Rebecca Tuck KC’s report. Bassett added that “[b]y disaffiliating, we hope that both organisations will feel greater pressure to change how they run, and to foster better relations with other Common Rooms”.

The disaffiliation will stand at least until Brasenose JCR reconsiders their affiliations again in a year’s time. The email sent to students added that the JCR would “soon be writing to both organisations to confirm this and to express our discontent”.

The SU told Cherwell: “[We aim] to ensure that all students feel represented by us. A common room choosing to disaffiliate is therefore a clear sign that we must work hard to improve our support, and listening to the student body about how we can develop a better SU is an absolute priority going forward.

“The SU President has reached out to Brasenose to discuss students’ discontents and how we can work with them to address any issues.”

Just last term, the SU itself held a referendum on affiliation with the NUS and voted to remain affiliated by 791 to 589, but with a turnout of only 5% of the student body.

This article was updated at 1pm on 14/06/2023.

Election succession for President-Elect Hannah Edwards has been suspended due to allegations of electoral malpractice. The allegations also affect the elections to Secretary’s Committee. An Election Tribunal will shortly be summoned to hear these claims.

The Union’s Returning-Officer (RO) wrote in a statement, published on the Union noticeboard, that he received four complaints of malpractice which “purport to affect the Office of the President-elect, Librarian-elect, Standing Committee and Secretary’s Committee”. The RO has since clarified to Cherwell that he received two valid allegations of electoral malpractice which purport to affect the Office of President Elect and Secretary’s Committee, and two other complaints which were passed to the Tribunal for consideration and subsequently ruled to be invalid.

This follows an election which saw markedly low voter turnout and mostly uncontested positions.

Edwards has been contacted for comment and this article will be updated to reflect ongoing developments.