A little past 9pm, a recent Oxford graduate got home from work and called me. Long day at the office? Not particularly, he said – he gets in at 6.30am. 14-hour days weren’t unusual.

He fine-tunes AI models for high-frequency trading, trying to profit millionths of the value of a high number of trades. Making 10 pence of profit on a bunch of £100,000 trades would be a success.

Studying physics and maths, he wrote a thesis on deep learning applications and spent much of his time trying unsuccessfully to get access to the high-powered computers he needed to run his experiments. Now, he has access to a much wider array of resources, but can’t work on the problems that innately interest him.

“I put an extraordinarily large amount of effort over decades into becoming a really, really good physicist, and there’s no reason for the progression of my future or my career or my bank account to ever look at any of those books again,” he said. He finds the problems he works on now stimulating to solve, but says “they aren’t meaningful, and they don’t matter – like, at all.”

The majority of recent Oxford graduates in the workforce feel that their work is meaningful and important to them – 81% in the most recent Graduate Outcomes survey. But there is a large group who end up in lucrative industries with dubious propositions for how they add value to society. The most prestigious institutions in the world are taking high-achievers, and sending them into roles whose social value is at best abstract, and perhaps nonexistent.

Rutger Bregman thinks these people are wasting their lives. His recent book, Moral Ambition, encourages the highly-motivated strivers of the world to completely reorient their aspirations. Ditch the well-trod path from Oxford to the City; forget the grad schemes and internships at the Big Four accounting firms. Instead, address the biggest problems in the world, from factory farming to nuclear security.

Bregman told Cherwell: “The most important question is not how hard you work, or how talented you are, or what your grades were in university. No – the most important question is what are you actually going to work on? Will you work at one of those boring banks? Will you work on rich people’s problems in rich countries, or will you take on one of those really neglected global problems, such as preventing the next pandemic, or taking on malaria?”

Shifting moral values

Bregman is generally an optimist. One of his books was subtitled “A Hopeful History”. But he recognises that there used to be more people on his side here.

In the 1960s, an annual survey of American college students showed that around 40% considered “being very well off financially” to be “essential” or “very important”. Even as the world around them has gotten richer and more comfortable, around 85% have said the same recently.

Britain’s old elite had a sense of noblesse oblige – that their privilege could only be justified by service to society. Today, many of those privileged to an Oxford education feel that they have earned their spot through merit, so can pursue their private interests and prestige above all else.

The author Bill Bryson, upon visiting Oxford in the 1990s, wrote that it’s “not entirely clear what it’s for, now that Britain no longer needs colonial administrators who can quip in Latin.” Much of that purpose now seems to be creating account managers to go down the M40 to the City of London. In recent years there has been even more competition among top talent for jobs in finance, consulting, and corporate law.

Those three industries are what Simon van Teutem, a DPhil student at Nuffield College, calls “the Bermuda Triangle of talent” in a recent book. He has seen many of his peers from his undergraduate and master’s years at Oxford get lost in the triangle.

“In freshers’ week I met all these brilliant people way more ambitious than me, way smarter than me with amazing dreams that they had already jotted down in their personal statements – politicians who wanted world peace, medics who wanted to cure cancer,” van Teutem said. “And then five years later most of my peers were not working for Doctors Without Borders, or a cool startup, or government, but were all at places like Morgan Stanley or Goldman Sachs or McKinsey.”

And so was he. van Teutem spent three summers working at banks and one at McKinsey. When he got a full-time offer there, he knew the ‘prestige escalator’ of pursuing higher positions might become his whole life.

“Everyone says ‘Oh I’ll just do this for two or three years and then I’ll get back to my dreams’ but in reality once they’re in that place, and their salary doubles every few years, and they’re surrounded by people who make more money than them, and they get accustomed to a certain lifestyle and have a mortgage… They might leave one employer, but then they go work for Shell, or BP, or Unilever, or private equity.”

“How Oxford grads are programmed”

van Teutem interviewed 212 people for his book. He identifies them as ‘insecure overachievers’ who have always been hard-working, ambitious, and anxious to win markers of high-status, whatever they may be. They are indecisive about careers, and consulting firms tell them that a job there doesn’t close any doors.

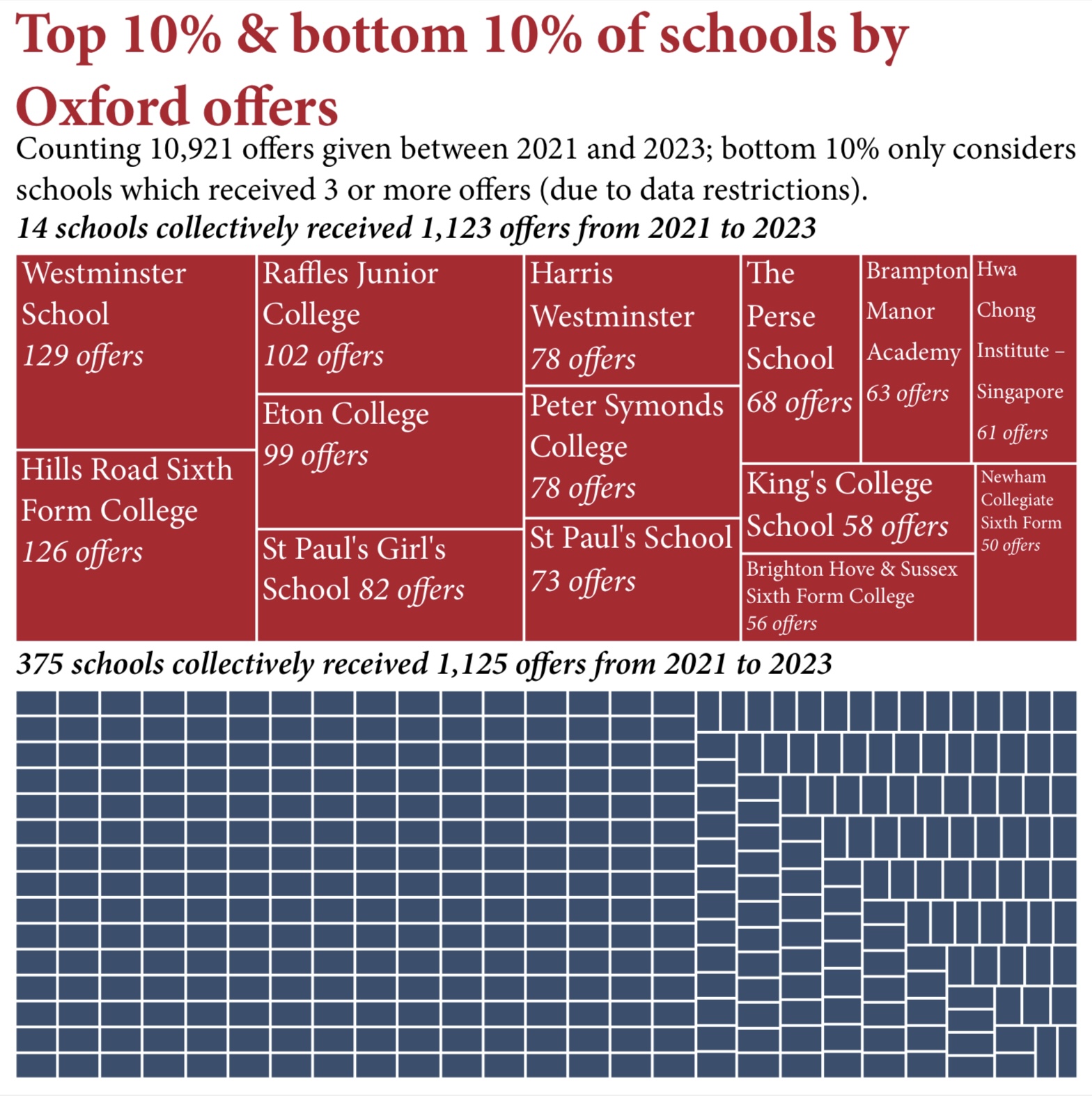

Elite universities are packed with them. An annual survey run by the Harvard Crimson show that in recent years, about 40% of graduates from America’s most prestigious university who go directly into the workforce take jobs in finance or consulting. The last few years, consulting hiring directly from Oxford has collapsed as the business model of having 22-year-olds tell other people how to run their businesses has come under question. Recent stats show that 12% of Oxford grads who take jobs immediately after graduating go into finance or insurance.

van Teutem said: “You have to understand how Oxford grads are programmed. Between 12 and 21, all they are doing is striving to jump through the next big hoop, reaching the next level. If you’ve been doing that for ten years, your natural impulse is like, ‘What’s the honours programme after the honours programme? What’s the Oxford after Oxford?’”

The student who makes AI models for high-frequency trading, anonymous to discuss employment, met a lot of highly-motivated and hard-working people at Oxford. They largely went down a few career paths.

“I know a lot of people who went into the finance industry in some capacity, and if you include law as well, it may even be most of the people I was close with at Oxford,” he said.

While he said his work is “abstracted away from impact,” he doesn’t think it is a totally ‘bullshit job’. If no one were to do it, investment would be more difficult and the economy wouldn’t work as well.

Bregman was unimpressed by that argument. He said that market makers, as with strategy consultants and corporate lawyers and the like, usually do provide some sort of value to the world. The tragedy is in the lost opportunities, which he tries to harness in the School for Moral Ambition.

“We’re talking about the country’s best and brightest, from one of the most prestigious universities in the world. And I think the world’s most ambitious people, the world’s most talented people, like him, should be working on solving the world’s most important problems. Is that really such a crazy thing to believe? It seems super obvious to me! If you’ve been given this extraordinary talent and privilege to go to one of the top universities in the world, maybe do something with it?” Bregman said.

While Bregman and van Teutem’s work is especially popular in the original Dutch, it is really tailored to an English-speaking audience. van Teutem says that while unrestrained ambition is encouraged in Anglo-American culture, in the Netherlands, one is not pushed to stand out as much.

But finding a normal but dignified vocation can be difficult too. Over the last few decades, jobs interacting directly with people or production have declined in number. Jobs sitting in front of a computer, from where it can be more difficult to see one’s impact, have become more and more common.

Of course, it’s possible that all that office work is just what it takes to organise a highly complex and prosperous modern economy, even if it isn’t immediately clear what everyone is contributing. But the late anthropologist David Graeber argued that a huge swathe of the world’s office work had been created for essentially no overall gain, not just a small number of talented lobbyists or advertisers. Graeber thought these ‘bullshit jobs’, perhaps making up 40% of all work in some countries and most of the office job nonsense you hear about, are an extraordinary waste of human time and potential that could be directed toward pursuits people genuinely care about.

So, if you want to have useful work for the decades to come, what skills should you develop now?

The murky future of work

The trouble is that no one knows. On the one hand, it’s easy: Bregman says that morally ambitious projects need all sorts of skills from PR and tax specialists to software developers. But today’s college graduates are facing an extra challenge: the rise of generative AI means it’s less clear than ever what the future of information work will be. How are you supposed to answer a job interview question about where you see yourself in a decade if you don’t know whether any of your skills will be useful then?

Fabian Stephany is a lecturer at the Oxford Internet Institute and researches the skills necessary for the future labour market. The problem is, even he isn’t sure what that future will demand.

He says that the most important skill is the ability to re-skill, but knows that’s not very helpful, and that it’s not anything new. Whereas previous waves of automation tended to disrupt manual jobs, AI is changing the labour market for recent college graduates.

Stephany told Cherwell: “I spoke to a partner at a law firm the other day, and he said, ‘yeah, we’re having problems right now justifying the costs that we’re putting on the bill for our clients’ because increasingly their clients say, ‘why is this costing us so much? Can’t this be automated? Can’t this be done by ChatGPT very easily?’ So the work of the paralegal, to name one of the entry positions, is under much more scrutiny than the work of an associate or a senior partner.”

An Oxford student who works virtually for a law firm is already feeling the pinch. His hours were recently cut after his firm got access to a new AI-based transcription service.

He told Cherwell: “My job used to be transcribing hours and hours of wire-tapped phone calls. Now, it’s going through and correcting the AI’s transcription, because it still makes a lot of big mistakes.” He doesn’t mind his hours getting cut because it has made the job so much easier.

The ChatGPT you can get for free is far too inconsistent to do the whole job of a paralegal. That model still cites legal cases that never existed and makes arguments with sometimes flimsy reasoning. But models with subscription-based services are much more powerful, and improving quickly.

Unlimited access to Deep Research, a subscription-based OpenAI product, costs $200 a month (£150). The New York Times’s Ezra Klein said it can produce a research report in minutes that matches what his highly talented teams take days to make. Suddenly, $200 a month doesn’t look like much compared to the wages of a whole team of top college graduates.

STEM jobs aren’t safe either. Many of today’s students were told as kids to ‘learn to code’ – the understanding was that this would inevitably lead to a stable and well-paying career in an ever-growing industry. But hiring in software development is now collapsing, perhaps because so much of it can be automated. At Google and Microsoft, AI now writes about a third of all code, a proportion that is rising fast.

What if AI keeps improving at coding and modelling and figuring out promising routes for research, to where it’s much better than any human at… AI research? Once AI development is itself largely automated, some leading researchers predict that we will create an artificial general intelligence (AGI) that rapidly soars past human abilities at every single cognitive and physical task. If they’re right, all the paradigms of this discussion of integrating AI in human work would go out the window by the time today’s freshers graduate. The much more pressing discussion, they say, is about aligning a future superintelligence with human values so it eradicates disease and poverty rather than releasing a bioweapon that ends the human race in 2030.

Most AI watchers are sceptical of those projections. Although Stephany uses AI to help his coding and literature reviews, he doesn’t foresee a superintelligence-dominated world, or even one in which AI will replace everyone’s jobs. In the long-term, he thinks employee productivity will rise but there will still be work for Gen Z to do. Stephany says that people who harness new technologies always stay afloat. It used to be the weavers who used new machines who prospered, and Luddites who didn’t adopt them went out of business. Now, white collar workers will have to do the same.

Once, it was only the hype-men of Silicon Valley who were seriously thinking about AI-based changes as being on the scale of the industrial revolution (or greater). Now, that analogy is broadly pondered. Pope Leo XIV was inspired to take that name by concerns about “human dignity, justice and labor” in an AI era. As Leo XIII offered Catholic social teaching for the age of factories and steam engines, this era will also demand hard thinking for a new age.

Die with your tools in your hands!

In American folklore, John Henry was a Black man who had been freed from slavery and did long, gruelling work building railroads. One day, the boss brought in a powerful new steam drill that would replace his entire team. John Henry said he’d die before letting that happen – “did the Lord say machines oughta take the place of living?” He set up a race against the steam drill, and won! But he was so exhausted that he died with his hammer still in his hand.

A great tale of the dignity of human labour. But you could also frame it this way: humans once had to do work that was so hard that it could kill the strongest man around. With new innovation, they don’t have to. Still, John Henry got a sense of purpose from doing that work to feed his family, and the drill meant his friends’ hard-trained skills became useless and they had to find new jobs.

In this new age, we must choose what work we want machines to do, and what work we want to keep for ourselves.

But John Henry’s story is only powerful because he is building something useful and real: a new railroad track that will transport real people and goods. The story wouldn’t work if his labours were building a train that went nowhere, or more effective PR strategies for tobacco companies. As Bregman said: the most important thing isn’t how hard you work, it’s what you work on.

We are racing into a brave new world, that has people and machines in it, writing and coding and ‘thinking’ side by side.

This will remain the most important thing: make sure that the projects you work on together are meaningful – maybe even morally ambitious. Be of use. Use a hammer or a steam drill; write your own code or write a prompt. If we do go down in the AI apocalypse, let us die with those tools in our hands.

But whatever tools you use, make sure you’re using them to go in the right direction.