“Both crews get ready please.”

Two boats sit on the Tideway, a flotilla of motorboats behind them, led by the umpire Matthew Pinsent giving orders over the speakers. Annie Anezakis grips her blade tightly as her face flashes up on the screen. This is her third year in the Boat Race—her first as president.

Daniel Orton’s hand shoots up. Oxford is not ready.

“Lilli, hold it.” The two seat squares her blade, and the tide swings the boat minimally to stroke side. “Easy. My hand’s coming down.”

“Oxford… Cambridge…” The umpire’s voice booms across the Thames. Sixteen rowers sit at front-stops, their blades slightly over-squared to stop the boats drifting with the stream. Concentration and ambition are written across their faces. This is it.

“Attention”—the red flag is up. The rowers are on the edge of their seats—”GO!”

The flag comes down. Two boats lurch forward as the rowers take their first strokes. The boat is heavy as seven women follow Heidi Long’s rhythm. One stroke. Two strokes. Three. The boat is moving at 43 strokes per minute—it’s fast, but is it fast enough? Adrenaline surges through their veins. Daniel’s voice sounds strong and clear through the boat’s speaker system.

“Complete, complete!”.

The boat starts to run more freely, fuelled by months of training and a boatload of nerves, but the Light Blue boat begins to pull ahead. Still, nothing is won, nothing is lost—every stroke counts.

There is a sense of urgency in Daniel’s voice, nerves channeled into command, tension reframed as pure motivation. Every call is delivered with precision, not a single word wasted, every one laser-focused. Raucous cheers from the riverbank barely register as thousands of spectators scream out their support for their university. Ambitious young rowers cycle along with the boat, dreaming of one day earning a place among the blues in the boat.

“Believe you can do it!”. The blades dig into the water, every muscle in Annie’s body straining. She’s following Kyra Delray and Heidi—Oxford’s stern pair. The sun shines as the shell glides away from Putney Bridge. The boat feels heavier than it should—heavier than it did during the morning pre-paddle, which had gone surprisingly well.

“It was probably one of the best sessions we’ve ever had”, Daniel will later reflect, “which is quite unusual, for a pre-paddle.”

50 seconds in, the rate has dropped to 39, the sprint is not yet over. Pinsent’s voice booms over the water once more.

“Oxford!”

He warns, as the two boats drift closer together. It’s not the rowers’ concern. They move up and down the slide with aching precision, muscles burning and minds going blank from the pain of the lactate searing through their veins. There’s no time for overthinking today; it’s all instinct, muscle memory, and colossal effort, Daniel notes.

“Oxford!” Pinsent bellows again. Bow-side clutch their blades tightly as the boats come ever closer.

“Stop rowing.” Cambridge has caught a crab.

“Both crews, stop rowing.”

One minute and 25 seconds in, a restart is ordered—an unusual occurrence, to say the least. The last time the Boat Race was stopped was in 2012, when Zoe de Toledo—ironically now sitting in the commentary box—coxed the Blues to a narrow loss. A swimmer’s head had bobbed up in the waves, right in front of the two boats. Fittingly, it was Matthew Pinsent who decided to stop the race then, too.

The boats line up again, Cambridge sits a third of a length ahead of Oxford. Pinsent lowers the red flag once more.

The race is back on.

Eighteen minutes and seven seconds later, it’s all over. The blue boat drifts towards Chiswick Bridge. Elated, exhausted cries echo from the light blue boat, lactic acid and emotion surging through every limb. Though Cambridge won by a margin of two and a half lengths, it was by no means a poor showing from Oxford. Having raced in WEHORR (the Women’s Head of the River Race in London), Cambridge had proven themselves the best university crew in the country. Oxford’s time today, just seven seconds behind, would have placed them right behind Cambridge in the ranking— and that, despite what felt like six months of torrential rain and an unrowable river (at least from a college boat club’s perspective)!

Early October 2024, Iffley Sports Centre, Oxford

The gym is buzzing with an air of anticipation as rowers cluster around the ergs in the Iffley Sports Centre. Annie stands among them, now in her third year with OUBC, this time as president. There are a lot of new faces, a lot of unfamiliar faces, a few girls she recognises—girls who have raced in blue boat, in Osiris, some even at the Olympics.

She stands with a few of the returning girls as they wait for the last few to wander in. “We talked about what mentality we wanted to take into this season,” she says. “What our leadership values were.” There’s a quiet determination to set the tone early—but for now, there’s also laughter, small talk, lightness.

Across the room, among the coxes, is Daniel. This is his first year trialling for Oxford. After many years of coxing at Latymer Upper School and having coxed at his college over the past year, there is still something intoxicating about standing in this room. He watches the rowers move around him, excited and chatty—this time is for getting to know everyone, to soak it all in and to meet the strangers who will soon become friends for life.

The erg screens flash, the machines hum, everyone is eyeing up the splits around them, “trying to suss out where you sit on the team”, Annie explains. But for the moment it’s easy. “No matter what pressures came up,” Daniel says, “having fun being there was the constant.”

The intensity will come, they all know it, the thought of selection hanging quietly in the background, but for the now it disappears, the infective energy making the first session pass by in a flash. The ergs are wiped down, layers put back on, and the ambitious girls leave with a smile on their face.

The first few weeks are about settling in—learning names, getting used to the rhythm of the new line-up of rowers. There’s no leaderboard yet, no divisions between the blue boat and Osiris. Just a group of girls, slowly building up a squad.

But underneath the easy smiles and casual ergs, there’s something stronger at play. Everyone knows the rivalry between Oxford and Cambridge all too well. Everyone feels the underlying pressure in their own way.

For Annie, Cambridge’s recent winning streak isn’t something to be afraid of. It’s fuel. “We spoke about how we had a chance to be the first Oxford women’s boat in a really long time to turn the tide,” she says. “We saw it critically as an opportunity, not a threat.” It never felt like a shadow hanging over them. If anything, it sharpens the sense of purpose: this squad isn’t carrying the past—it’s building something new.

Daniel feels the same. The streak, he says, doesn’t change the daily process. “You can only put your all in every day—you can’t do anything different or anything more because you lost the last year or the last five years.” Instead of weighing them down, the history around them adds momentum. “It feels like a really exciting time in the club,” he says. “The losing streak is motivation to fuel an exciting change.”

The past can’t be rewritten. But these are the people shaping the future—one session, one stroke, one decision at a time.

Late October 2024, Iffley Sports Centre, Oxford

The atmosphere is different today.

Gone is the easy energy of the first few weeks, replaced by a tight tension. It’s 2k day—the first major test of the season—and everyone can feel exactly how much it matters. Seven minutes of intense pain, one flashing screen, all resulting in one score next to your name.

For Annie, the feeling is familiar—but no less nerve-wracking. She’s not a huge fan of the erg. “Some really fast, quick, strong movers come in,” she says. “And I’m always like, oh god—there goes my seat.” No spot is ever guaranteed, not even after crew announcements, she admits.

The pressure today is personal, but it’s not selfish. That’s something Daniel noticed early on at Oxford: the subtle but powerful shift in mindset. “We want all of our boats to beat Cambridge,” he says. “And you really, really hope that the best chance of that involves you getting your seat —but ultimately, the main thing is that you want Oxford coming out on top.”

The erg room hums with the sound of split times ticking upwards, heart rates climbing, coxes and coaches screaming, every stroke more painful than the last. It’s just you and the erg, it’s easy to feel like it’s you against the world.

But it’s not, not here.

Over the past few seasons, Annie’s seen that change first-hand. “It’s not about which boat you’re in,” she says now. “It’s about your boat against Cambridge. About being greater than the sum of your parts.” Even in the sharpest competition, the pack mentality holds. Push each other. Drive each other. Make every crew stronger.

Today, the erg splits will go up on the wall. There will be quiet celebration, and there will be disappointment. There always is. But through it all, something bigger holds steady: 18 rowers, one goal.

When Annie pulls her final stroke and slumps forward, gasping for air, it’s not just about her time. It’s about being part of something that, inch by painful inch, is moving forward together.

January 2025, Cerlac, Spain

The sun beams down on the rowers, sitting on the long, open stretch of water. Even in the middle of Spain, the water feels the same—no flooded boathouses, no cold, grey mornings—and yet, with a blade in hand and miles of river to cover, the girls’ muscle memory and immense effort stays the same.

Clear skies and a smooth river, training camp is beautiful. It’s also serious.

The squads train together, side by side, but the Boat Race is inching closer, right on the heels of the boats gliding across the water. Annie looks around at the faces that are no longer strangers, now some of her best friends. “A great camp”, she says. “Definitely more productive than the Tideway.” In between sessions there are quiz nights and dinners filled by laughter and a deep connection between the rowers. And yet, on the water, the atmosphere is shifting. The boats are closely followed by the launch, every stroke producing watts, every watt a consideration for selection.

This is when it really starts to matter.

Injured athletes have returned, Kyra Delray, who will fill the seven seat in the Blue Boat, for one. Selection pressures permeate the once easy atmosphere, especially in the post-holiday period. It’s not easy to train throughout the holidays, even the Boat Race athletes can attest to that. “When I was at Princeton and even in school,” Annie says, “I hated training across holidays. Christmas Day, I just wanted to chill. I didn’t want to do anything.”

But the Boat Race was different. It sharpened everything. The season was short. The stakes were simple: one race, one opponent, one winner. “You’re a winner or you’re a loser,” Annie says. And there was no hiding from that. No excuses. Not anymore.

“You can’t slack off,” Annie explains. “You have to train every day because you’re going to come back and be put to the test.” Allan’s watching. The coaches are always watching. Christmas is barely behind them, but Annie’s already moved past it. “I remember saying to my mom,” she laughs, “‘My head’s not going to come up from under the water until post-Boat Race.’ I’m under the pump now.” There’s no more time to drift. No more holidays. No more rest days.

It’s around this time, too, that Daniel starts thinking differently about his own role. In previous years, coxing had just been part of showing up—row, race, learn as you go. But this season, he approaches it deliberately. “You can get so far just by putting effort into your own coxing development,” he says. Setting tiny goals for each session, listening back to recordings, asking: How do I want to sound? What can I sharpen, even just a little? “It doesn’t have to be big,” he says. “But if you give yourself clear focuses, you can build so much more than you realise.” Quietly, methodically, he’s stacking up improvements of his own—one session at a time.

The fun of the autumn is still there, somewhere, but it’s buried now under layers of expectation, ambition, and urgency.

There’s only one Boat Race. One shot. And the road to it is built stroke by stroke, here in the Spanish sun.

March 2025, Oxford

The day crew selections are announced doesn’t quite feel real. The energy in the room is almost indescribable—tension, relief, disappointment, the unreal feeling that, somehow, after months of training, the boats are finally real.

Annie has been through it before, but it doesn’t get easier. Outside the squad, there’s endless talk in the media—that Oxford wants it too much, that they don’t want it enough. Winning is everything. And yet it’s not the only thing that matters.

Inside the club, this atmosphere isn’t reflected. Daniel thinks back to those first few months—how easy it had been to focus in showing up and giving every session your all, the Boat Race looming in the distance. Even in the face of selection, the sense of being part of something larger than yourself was an attitude that always stuck.

Daniel had coxed all sorts of crews so far, the men, the women, the blue boats, and the reserves. “You end up coxing a lot of different boats and a lot of different experience levels,” he says. “And that’s actually really good for your coxing as well.” But when he announced to his college boat club that he had made it into the Blue Boat, we all cheered for him, and he beamed back.

By March, the friendships are undeniable. Crew dinners, brunches, endless inside jokes. The late-night trip to London to see Wicked becomes a running theme—even in Tideway Week, the squad can’t stop singing the songs. “It’s just all the little things,” Daniel says. “You have to love the little things. Otherwise it’s too much effort, too much time.”

Somehow, despite the pressure, despite the stakes, the squad feels stronger than ever. They were never just two boats, they were a team, and now they’re ready.

April 4th 2025, London

By the time Tideway Week arrives, everything feels closer. Everything is closer.

The squad moves into a house in Putney, packed together like the world’s fittest Big Brother cast. They eat every meal together, parents take turns cooking for the squad, and they spend evenings talking about the boat race, discussing strategy (though a timekeeper was instated when the rowing talk became too much)—and when they’re not planning for the Boat Race, they’re singing songs from Wicked at the top of their lungs. “It’s so fun,” Annie says. “You don’t get sick of anyone.”

On the water, the atmosphere is just as close. Every day, they train on the Tideway, weaving through the tricky bends of the course they’ll race on. Daniel soaks it in. “It’s the last big eight days of the season,” he says. “You’re living together, training together, getting really close—and you just enjoy it.”

There are stresses—of course there are—but the squad manages it well. “You can’t ignore the tension,” Daniel admits, “but we did a really good job of being there for each other when people got stressed.”

Still, as the week goes on, the outside world starts to creep in.

The BBC wiring goes up along the riverbanks. Crew announcements hit social media. There’s a press conference in the middle of the week where Heidi Long and James Doran field questions from reporters, their faces broadcast to strangers. Watching it, Daniel feels a jolt of reality: “The Boat Race is in five days. It’s exciting. It’s a little terrifying, too.”

For Annie, though, the pressure runs deeper. She’s not just the six seat, she’s the president. After years in the squad, “I just wanted to be able to have a lasting impact,” she says. Shaping the culture, pushing the team forward—it was what had motivated her to give her 150% every day through the season.

But now, with the race just days away, the weight of it catches up. “Boat Race week, it did become a little overwhelming,” she admits. It’s not just about her own performance anymore. It’s about everyone else. “Are we making the most of every day? Is everyone getting the most out of themselves?” The questions linger in the back of her mind as the race draws closer.

It mattered because rowing had always been more than a sport for Annie. She’d found it back in high school—almost by accident, through a PE class. “I was really bad at it at first,” she says, laughing. But somewhere along the way, she fell in love with it. “It helped me find my community,” she says. “Everyone that does rowing is weird in their own way. We’re a special sort of person.”

That was why this team, this Boat Race, meant so much. It wasn’t just about winning. It was about being part of something built by people who understood her, who pushed and carried each other through every hard moment. She had found her people here. Now it was about making sure they found the best version of themselves, too.

Maybe that’s why, inside the house, they find ways to ground themselves. For Annie, that means slipping back into the rhythms of normal life—or something close to it. “When you’re not at the river, you’re probably working,” she says. Exams are still looming, coursework still needs submitting. In a strange way, it helps. “It grounds you,” she reflects. “You remember that you’re just a student at the end of the day, trying to make a boat go fast.”

And so they keep rowing.

They keep studying.

They keep singing Wicked.

(They keep talking about rowing, over and over again.)

And they wait for the moment when they get to prove all of their hard work has paid off.

April 13th, 14:21, The Tideway

The moment has come. There is nothing new to say, no last-minute strategies can save the day. For Daniel, it’s all about instinct when you’re in the boat. “You think when you train. In the race, you know what to do.” Seven months, and years before that, of hard training, to build the reflexes and strength they were trusting in this moment.

It was all about trust. Trust the routine, trust the normal, race day is just another day—or at least that’s what it should feel like. “If you do something really different on race day, it’ll freak you out,” he says. “You just have to trust your normal process and that will allow you to have your best performance .”By the time they sit at the start line, the work is done.

For Annie, this moment, above all, is about taking it all in. Take in the noise of the crowds, the attention of the media (because really, when else do the media care about rowing this much?), and the familiar feeling of the waves shaking the boat. She had let the moment rush past her in earlier races. Not now. In the final moments before the flag drops, she focuses on just one thing: trust the crew.

Around them, the circus of the Boat Race builds: BBC cameras, umpire flags, thousands of spectators. Inside the Oxford boat, none of this matters. What makes these 8 women out is their willingness to push beyond their comfort zones, to keep pushing on and on. They will fight even when behind, even when it hurts. That’s why they are where they are.

Even when the race is stopped, even when chaos could break out—they’ve talked this through, they keep going. Annie feels it in the crew around her—a steadiness, a resilience that didn’t exist seven months ago. When she calls for the ‘Brooke’s start,’ it’s not desperate, it’s familiar.

And she keeps shouting, ‘Yeah, yeah’, every other stroke until she can’t yell anymore. This feels good, this feels better than the first start. And there is hope.

During the race, the pain is predictable. The belief is not.

Annie has rowed this course before, has rowed in boats where the margin defeats the home, in boats where one length down felt like a race lost with miles to go. Not this time. “I believed we could win until the last round,” she says. Every time Daniel calls another ten, every time Annie sees the girls in front of her digging deeper, hope tugs at her again. One more stroke. One more push. One more second of belief.

In the end, it’s not the margin that matters. It’s the fight.

And maybe that’s the real secret of the Boat Race. You don’t win or lose at the finish line.

You win in your relentless determination, when it would have been easier to give up. You win by building resilience in the face of agony.

And even more importantly, you win as a team, even if you lose.

April 13th, 14:55, The Tideway

After the race, everything blurs.

They sit quietly at the finish, the shouts of the crowd echoing across the Tideway, the BBC cameras already moving in. Exhaustion, disappointment, and grief slowly sinking in. Despite a brilliant performance, it just wan’t enough.

Annie stands beside Daniel, waiting for the post-race interview. Something sort of *wicked*, “The fact that you’re about to be shown live on TV after losing something you care so much about.”

At that point, all she has left is raw emotion. “I love this team,” she says. “I love everyone around me. This has been the best season ever—and this one result doesn’t define them.”

There is sadness, yes. There always will be.

But stronger than sadness is pride.

Being part of OUBC isn’t reserved for a 19 minute stretch along the Thames, it’s for life. “It’s so special,” Annie says. “You have this network of just really impressive, amazing people—all of us connected by the same gruelling experience.”

At the Boat Race dinner that night, surrounded by past winners and past losers, Annie feels the weight of that history. “Only people who’ve done it really understand,” she says. “It’s so hard. It’s so raw.”

And in that shared understanding, there’s comfort. A reminder that win or lose, they belong here. That this race—and this year—will never be just a line on a CV.

It will be something they carry with them forever.

April 21st, 16:00, Radcliffe Camera, Oxford

I’m almost late again, as always. As I rush towards the RadCam, I keep an eye out for the face I’ve been following in the Tideway documentary for weeks now. I still can’t quite believe I’m about to have coffee with Annie Anezakis.

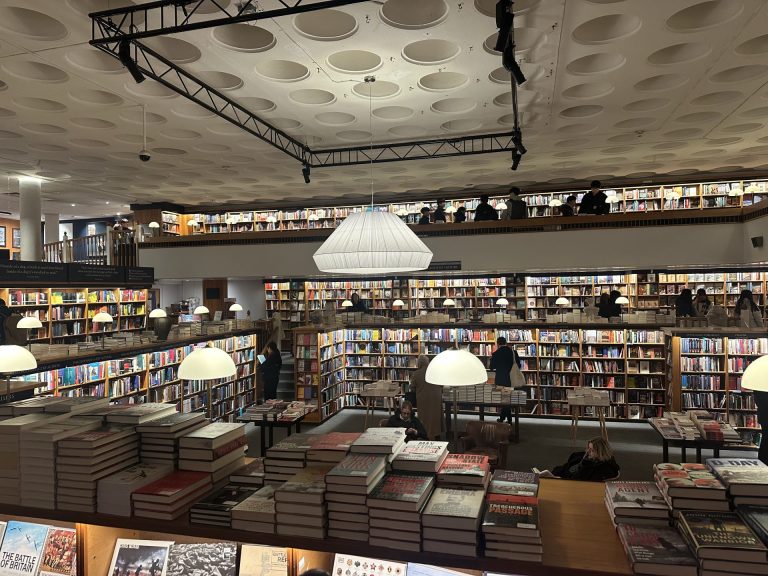

As we walk to Blackwell’s, we fall into the usual small talk: How were your holidays? How are you finding being back in Oxford? What college are you at?

Merton, I say.

“So you know Dan?” she asks, smiling.

I do know Daniel—we’d called a few days earlier. It was during that conversation that I asked him about his plans for the future, what he was thinking about after the Boat Race.

Training will continue into Trinity Term, though with a different energy. “It probably won’t be quite like the lead-up to the Boat Race,” he says. “It’ll be more about enjoying it—getting tons out of it, but less crazy intense.”

Summer will mean regattas—BUCS, Henley Women’s, Henley Royal—with squads mixed and reshuffled depending on eligibility and ambition. Some teammates are chasing GB trials. Others are just racing for the joy of it.

And beyond the summer?

Daniel hasn’t decided yet. “In all honesty, I haven’t given next year any thought,” he says. “I just need to sit down and think about it over the next few weeks.”

For now, there’s time. Time to enjoy the sport, the friendships, the river.

Time to breathe after a season that asked for everything—and gave so much more back.

Annie tells me I’m the first person she’s spoken to about the Boat Race outside of her family and housemates. I feel honoured—and still a little in disbelief that I get to spend the next hour picking her brain on every question I can think of. I ask about trialling, about every niche curiosity I’ve ever had about OUBC—and, of course, about her plans for the future.

BUCS is just two weeks away, and Annie isn’t slowing down. “We always wanted to put more time and effort into summer rowing,” she says, “to keep building the program and come into next season ahead of where we finished.”

Summer racing will be different—more flexible, more balanced around academics—but the fire is still there. Henley and European University Champs are on the horizon.

And after that?

Annie’s first priority is finishing her degree—passing her exams, and then she’s going back home. It will have been seven years since she left home. And yet, the idea of another Boat Race season is already tugging at her. “I’d be very surprised if I didn’t do another one,” she says. “I just love it, you know?”

Not as president next time. And with a little less responsibility. But the river still calls.

Rowing, after all, has never just been a sport for her. It’s a home. And it’s a home to which she will always return.