Cherwell Mini #25 – New Year’s Mini

‘Dark, revealing, gripping’: In conversation with the cast of ‘JACK’

JACK, by Musketeer Productions, reimagines the cult story of the most notorious serial killer in British history. Shining a light particularly on the mistreatment of women and the brutality of the Ripper murders, the show carries a dark, punky aesthetic with a striking score and a vivid story. This new musical by Oxford graduates Sahar Malaika and Samuel Phillips had a sellout run in Oxford early last year, as well as at the Edinburgh Fringe festival last summer, and is set to come to the Courtyard Theatre in London on 5th January.

The musical takes place in London, 1888, a city thrown into panic by the recent murders of prostitutes in Whitechapel, attributed to Jack the Ripper. The play follows his final victim, Mary Kelly, days before her death, as she gets caught up in the investigation. Sitting down with cast members Liv Russell (Mary Ann Nichols), Sorcha Ní Mheachair (Nell), and newcomer Cameron Maiklem (Aloysius Howell), I asked them what they found so appealing about the play, and what’s in store for audiences in London.

Cherwell: Can you describe JACK in three words to start us off?

Maiklem: Dark, revealing, gripping.

Russell: Compelling, exhilarating, eye-catching.

Cherwell: How has JACK evolved since its first Oxford showing, and what can we expect to see in London?

Mheachair: The show has really focused its message. The heart of this piece has always been giving a voice to the women who were killed and exploring themes of misogyny in the time period. Fans should be excited to see new angles being explored, like the manipulation of women’s stories by men in the press, not just the police. As well as some more solo content for each of the ‘Unfortunates’.

Cherwell: Introduce your character to us.

Maiklem: Howell is, simply put, slimy. He sees people as players not individuals, characters he can manipulate and repaint to tell his own compelling, yet usually inaccurate, narrative in the papers. While he is not a murderer, he certainly exhibits all the traits of a villain you love to hate.

Mheachair: Nell is a complex character. She’s invented for the stage but based on many real women who did stay with Mary Kelly in her flat. Nell is a former prostitute who has fallen in love with Mary and is both grateful for the shelter and comfort Mary offers her, while still being hesitant and untrusting of the idea of relying on someone else. Nell’s life has not been her own and she has had to look out for herself since birth, making her own money the only way that was available to her, and throughout the play we see her struggle to let go of this need to protect herself by maintaining distance and independence.

Cherwell: What is your favourite moment or line in the play?

Russell: The song ‘To Catch a Ripper’. It is such a monumental part of the show – Rosie’s choreography is amazing and the effect of the whole cast singing bits of previous songs from the show gives rise to a really impressive number, as well as being a shocking and crucial plot point.

Maiklem: The chief’s line “piss off” (the most appropriate response to Aloysius Howell ever).

Mheachair: The word ‘unfortunate’ carries a lot of weight in this piece. It’s the title of the main theme and a blanket term to refer to the main characters of the show: the women. I really like when Howell (a slimy reporter) teases Alfie by comparing his failures to the low status of these women by taunting him at the end of an investigation: “Wrong again, sir, sorry. How unfortunate.”

Cherwell: How has the play shaped you as a performer?

Maiklem: This is my first time working on an original musical, so this journey has really developed my focus on characterisation in the early stages of rehearsal. I found conversations with the writer and directors, as well as sitting with the script myself, to be invaluable. It felt so refreshing to create my own character without the influence (whether conscious or not) of previous performers’ iterations.

Cherwell: What has been the most exciting aspect of this journey?

Russell: I just feel really lucky that I get to be a part of such an amazingly written, exciting new musical and also to be part of a team of such incredibly talented people that I am in awe of.

Maiklem: The most exciting aspect of this journey has been joining the team as both a new cast member and completely new character. It had felt like a huge responsibility but one that I have felt so lucky to bear. Roll on show week!

JACK runs from the 5th to the 11th January 2026 at The Courtyard Theatre, Pitfield St., N1 6EU.

‘The political is also political’: Ash Sarkar’s ‘Minority Rule’

Universities have often been seen as bastions of radicalism. Forgetting the fact that higher educational institutions, particularly ancient and elite ones in the Anglophone world, are governed by centuries of tradition and incubate the next leaders of the establishment, many people think of Oxbridge as moments away from starting a second May 68. There’s nothing the right-wing media love bashing more than their tired stereotype of out-of-touch students sipping oat flat whites and pontificating about the latest unfalsifiable nonsense coming out of the critical theory departments.

As fictitious as this caricature may be, it is true that educational level has started to be a major dividing line in voting intention and political opinions. UK politics over the last decade or so has upended many assumptions about the natural structuring of the left-right divide, with the Labour party now receiving most of its support from the middle-class (educated professionals), having seemingly lost traditional heartlands in the North. This has led to many centrists chasing an impossibly wide spectrum of voters, as exemplified by the disgraceful attempts of Keir Starmer’s government to rightwardly outflank Reform on immigration, despite the fact that his party risks losing far more voters to the Greens than the far-right.

What has happened to the left and the politics of community, equality, and dignity it is meant to support? This year, a brilliant book by journalist Ash Sarkar, Minority Rule, argues that a combination of right-wing inflammation and left-wing self-harm has shifted the political battlegrounds from economic and material factors to an obsession with what Sarkar calls ‘minority rule’ – the “paranoid fear that identity minorities and progressives are conniving to oppress majority populations”. Rather than focusing on financial issues such as energy, food, and housing prices, political discourse is saturated with hyper-toxic debates on immigration, transgender identity, and ‘cancel culture’. Sarkar’s diagnosis of the hysterical ‘culture wars’ points the issue to two places: a right-wing media that amplifies the voices of a few extremist politicians and uses statistical rarities to construct fantastical narratives, and an identity-obsessed left which has become more concerned with trivial semantic debates and the appearance of moral purity than substantive political and economic issues. Left-wingers at Oxford and other ivory towers would do well to take note.

Sarkar, an editor at the left-wing Novara Media, has attracted some prominence in recent years for clashes with prominent figures, including a debate with Piers Morgan where she declared she was “literally a communist”. Minority Rule is written in a breezy, accessible, and amusing style, which romps between using expletives and quoting Stuart Hall at length. The most engaging, provocative, and original part of the book is the opening chapter, which directs her ire towards those on the left she sees as stymieing the cause. Later chapters, which put great emphasis on the role of the media in creating political dividing lines, are also insightful and trenchant, but occasionally digress too far into personal disagreements with particular journalistic interlocutors. With the subtitle ‘Adventures in the Culture War’, it’s not surprising that the book is filled with outrageous, frustrating, and unbelievable stories and incidents, but sometimes the enumeration of particular events within the culture war (which it’s better to try to forget about) comes at the expense of greater elaboration and reflection.

As the emphasis on ‘minority’ suggests, Sarkar’s key concern in the work is to draw out a process of division and polarisation within the working class, a group whose interests should, from her Marxist perspective, be aligned. Sarkar is keenly aware of the difficulties in conceptualising the group of people she wishes to talk about. Indeed, the very difficulty in doing so gestures towards one of her central theses – how cultural issues have distorted the traditional ‘class consciousness’ and sense of shared interests. She writes: “Rather than shaping a sense of class identity around shared material and economic conditions … it’s instead defined by political and cultural outlooks.”

The right-wing media and politicians have not only created a dangerous frenzy on issues such as immigration, they’ve managed to turn the debate into one that ostensibly divides by class: affluent middle-class liberals in metropolitan cities are set against authentic working-class communities in neglected areas of the country. There is an increasing sense that ‘working-class’ refers to an identity and way of life rather than a material status. Sarkar incisively demonstrates how the same politicians and commentators who, ten years ago, publicly demonised the working-class as “chavs”, now lament the fate of the ‘white working class’, introducing a racial focus that inflames cultural division rather than ‘levelling up’ communities. Such right-wing rhetoric falsely creates the impression of a zero-sum game in which progress towards racial equality necessarily comes at the expense of improving the living standards of others.

The most interesting part of Sarkar’s work is the challenge she raises to the contemporary left. In the first chapter ‘How the “I” Took Over Identity Politics’, Sarkar explains how the once-radical idea of ‘identity politics’ – originated by black feminists to draw attention to how race intersected with class and gender – has become, in Sarkar’s words, “confused, atomised and oddly unambitious”. Rather than focusing on combating inequalities and entrenched institutional problems, the raison d’être of much momentum on the left has become dealing with problems such as ‘microaggressions’ and linguistic correctness. Sarkar highlights three particular problems: the notions of irreducible difference, competing interests, and unassailability of lived experience. These have led to a focus on performativity rather than genuine progress, and a culture of intolerance. The left has, in Sarkar’s brilliant phrase, “absorbed the idea that the personal is political, at the expense of remembering that the political is still political”.

Sarkar argues that there has been a great overcorrection. Until recently, the white man with a BBC accent was the ultimate authority – and in many, many places, he still is. But amongst progressives the admirable impulse to listen to others – to understand others – has been so greatly elevated that, in some spaces, the appeal to lived experience has become a rhetorical move that carries an automatic veto of any opposition. Irreducible difference supports this: if one’s experience as, say, a gay man or trans-woman is radically incommensurable with that of a cis-gendered straight man – as Thomas Nagel thinks a bat’s is with a human’s – then naturally you won’t wish to question a claim they make which is grounded in it. Sarkar argues that these barriers of lived experience are not unimpeachable and that such divisions lead to the deeply problematic idea of competing interests – the belief that even though someone agrees with you on a hundred different issues and shares the same socio-economic position as you, that, if they disagree on a single issue, they are no longer a viable political ally. This logic, which creates an inability to work together for the greater good, also opens the door to right-wing exploitation – it allows people to pit the projected interests of the white working class against minorities living in deprivation in London.

This obsession with an all-or-nothing view of politics unfolds constantly in universities. I recall a feverish argument over a JCR motion supporting Palestine because there was disagreement whether it should also show support for Jewish students facing antisemitism. The idea that there is a single dimension to progress, that solidarity requires complete and utter agreement, and that minor issues can be allowed to get in the way of real problems is an affliction that the left must purge if it is to get anywhere. Even Sarkar’s own last chapter, which ends with an impassioned call for unity against rentier capitalism, fails to live up to her otherwise rigorous defence of toleration. Her attacks on landlords and property owners feel overly crude and ad hominem, fostering an antagonistic mindset which eschews the possibility of democratic solutions. However, Sarkar, as “literally a communist”, probably wouldn’t care too much for my Rawlsian view of reasonable agreement. Are we radically opposed, incommensurably different, utterly at-ends, in the fight for progress, then? Of course not!

Minority Rule was published by Bloomsbury.

Best Japanese Homeware Gifts and Where To Buy in the UK

If you’re searching for Japanese homeware that feels special (and actually gets used), the best gifts tend to be the quiet heroes of daily life: a beautiful cup that becomes someone’s “morning one,” a textile that solves a practical problem in a graceful way, or a little object that makes a home feel calmer and more intentional. The joy of Japanese gifts is that they’re rarely loud—they’re considered, functional, and often rooted in craft traditions that have been refined for generations.

Below are some of the best Japanese homeware gifts to buy—ideas that work for housewarmings, birthdays, weddings, or “just because.” I’ll also share a simple way to choose the right piece, whether you’re gifting to a minimalist, a maximalist, or someone who “already has everything.”

1) Japanese tea cups and matcha bowls (chawan)

A handmade cup or matcha bowl is one of the most timeless Japanese gifts you can give. It’s intimate without being personal, and it instantly upgrades a daily ritual. Look for pieces with subtle glaze variation—those small, imperfect details are often where the charm lives.

Why it’s a great gift: practical, heirloom-worthy, and easy to pair with tea or sweets.

Gift tip: add a small tin of sencha or matcha for an instantly complete present.

If you’re browsing for authentic pieces, start with a curated Japanese homeware store such as Kawa London, which is based in the UK with all products from Japan.

2) Furoshiki wrapping cloths (the gift that keeps gifting)

A furoshiki is a traditional Japanese wrapping cloth that doubles as a tote, bottle wrap, picnic cloth, or scarf. It’s sustainable, endlessly reusable, and surprisingly modern—especially in bold patterns or refined indigo tones.

Why it’s a great gift: eco-friendly and versatile (great for friends who love design).

Gift tip: use the furoshiki as the wrapping for the present itself.

For more easy-to-gift finds, take a look at a dedicated Japanese gifts selection.

3) Tenugui towels and Japanese textiles

Tenugui are lightweight Japanese cotton cloths traditionally used as towels, head wraps, or kitchen cloths. Today, they’re also framed as wall art—ideal if you want Japanese homeware gifts that feel decorative but still practical.

Why it’s a great gift: affordable, beautiful, and easy to post.

Gift tip: choose a motif that matches the recipient’s vibe (waves, seasons, florals, geometry).

4) Incense and subtle home fragrance

Incense is a classic Japanese home ritual—more about atmosphere than heavy scent. For a gift, opt for calming notes like hinoki (Japanese cypress), sandalwood, or light florals.

Why it’s a great gift: creates instant “home” energy; perfect for small spaces.

Gift tip: pair with a simple incense holder for a complete set.

5) Chopsticks, rests, and small tableware upgrades

A set of Japanese chopsticks and ceramic rests is a deceptively brilliant gift. It’s small, affordable, and turns any meal into a moment. Look for natural wood tones, lacquer finishes, or understated patterns.

Why it’s a great gift: compact, useful, and feels premium.

Gift tip: add a small dish for soy sauce or snacks for a cohesive table setting.

6) Donabe pots and cooking essentials (for the serious foodie)

For someone who loves cooking, a donabe (Japanese clay pot) is a showstopper. It’s associated with warm, communal meals—hot pots, rice, simmered dishes—and becomes the centrepiece of a kitchen.

Why it’s a great gift: meaningful, functional, and made for sharing.

Gift tip: include a simple recipe card (e.g., rice in donabe, or a winter nabemono).

7) Bento boxes and lunch accessories

A well-made bento box makes weekday lunches feel intentional. This is a particularly good Japanese gift for students, office workers, or anyone trying to eat more mindfully.

Why it’s a great gift: encourages better habits; practical for everyday life.

Gift tip: pair with chopsticks and a small cloth for wrapping.

How to choose the right Japanese homeware gift

When in doubt, use this simple checklist:

- Everyday use: Will they reach for it weekly? (cups, textiles, chopsticks = yes)

- Space-friendly: If they live in a small flat, choose compact items (incense, cloths, small ceramics).

- Quiet design: The best Japanese homeware blends in, then becomes indispensable.

Where to buy curated Japanese homeware and Japanese gifts

If authenticity matters, buying from a store that’s genuinely focused on Japan makes a difference. Kawa London is a curated online destination for Japanese homeware, Japanese gifts, vintage clothing, and unique finds—100% Japanese and selected with an eye for quality and character. When your gift has a story (craft, tradition, material), it naturally feels more special.

Quick FAQ

What are the best Japanese homeware gifts?

Tea cups, furoshiki cloths, tenugui textiles, incense, and small tableware upgrades are among the most practical and loved Japanese homeware gifts.

Where can I buy authentic Japanese gifts online?

Look for curated shops that specialise in Japanese-made items and clearly source from Japan—like Kawa London’s Japanese gifts collection.

Are Japanese homeware gifts good for housewarmings?

Yes—Japanese homeware is ideal for housewarmings because it’s functional, stylish, and suits many interiors without feeling too personal.

£17,000 on grass, redacted files, and 250,000 parcels: Cherwell’s 2025 FOI review

As the Cherwell Investigations team, we take our job very seriously. A big part of what we do is Freedom of Information (FOI) requests – which allow us to ask for information on any topic (yes, any!) from public authorities, for example the University and colleges.

Cherwell handles a lot of data, but unfortunately, not everything can make it into our fantastic print editions. So, dear reader, we thought we would treat you with some of our best finds of the year, curated by our excellent investigative student journalists.

Expensive grass

Do you think that the University has its financial priorities straight? At Cherwell, we’re not always so sure, so sometimes we simply ask them how much they spend on things! Recently, we wanted to check how much it cost to refurbish the lawn outside of the Radcliffe Camera this September.

That amounted to an eye-watering £17,854.40, which – according to the University – “included labour, topsoil, and turf”. In their defence, the grass did look really good, but maybe they could have saved a bit of cash and done without the squiggly lines.

Following the OA4P encampments outside the Natural History Museum and around the Radcliffe Camera in Trinity term 2024, the University had spent £44,699 and £19,771 for each site respectively on grounds maintenance and returfing. Compared to the Vice-Chancellor’s £666,000 pay package, perhaps it’s not that bad – at least students (and tourists) get nice lawns out of it! The University said that “repairs were carried out to a standard appropriate to the damaged property”.

Release the files!

It was recently reported that Oxford had repeatedly mishandled sexual harassment complaints involving senior male academics. Professor Soumitra Dutta, the former Dean of Saïd Business School, stepped down from his role in September after the University upheld several harassment complaints made against him by a female academic.

Cherwell attempted to investigate the matter, and submitted several FOI requests regarding Dutta’s appointment. The University did comply, but appears to have taken notes from the Trump administration on how to redact documents (read: black out absolutely everything), citing personal data and GDPR exemptions.

Schrödringer’s CCTV footage

One of the contentious points of the University’s controversial disciplinary proceedings against the protesters that broke into the Wellington Square offices in Trinity Term 2024 was the CCTV footage of the reception. The University claimed that the recording proved that an activist assaulted the receptionist, which OA4P vehemently denies and claims instead that the footage “disproves the false allegation that acts of violence took place”.

Thames Valley Police did not pursue the charges against the protesters, and the University’s case was ultimately dropped on procedural grounds. Cherwell journalists tried to obtain this CCTV footage, used on multiple occasions during disciplinary hearings according to our sources, but hit a brick wall. Or rather, a shifting, moving, vanishing brick wall, Diagon Alley style.

The University responded with an exemption on November 14th 2024, admitting that it held the data but refusing to disclose it on the grounds that, after grouping the FOI requests together, locating the information would be too time-consuming. On March 3rd 2025, they told Cherwell that they didn’t hold the footage anymore, which had been deleted “in line with the retention provisions in the University’s CCTV code of Practice”.

However, on May 27th, the pivotal evidence magically reappeared! Responding to an FOI request, they once again declined to disclose it, claiming this time a personal data exemption. So, do they have it or not? The University told Cherwell that “an error was made in good faith in the March response, [and] there was no pretence by anyone”.

Bezos on top

You didn’t know that you needed this information, but you’re getting it anyways. Cherwell made some unlucky porters compile lists of the number of parcels received by each college, as well as a breakdown by courier. Unsurprisingly, Amazon comes up on top – with around 38% of all parcels being delivered courtesy of Jeff Bezos.

On average, colleges received around 3,000 parcels in Michaelmas terms, and around 2,000 in Hilary and Trinity. Blame the freshers ordering room decoration online? A clear outlier was Worcester College, ordering over 6,000 parcels per term on average last year. Either Worcesterites are online shopping addicts, or their lodge has a logging issue.

All in all, based on data from 12 colleges – the others did not comply or did not hold the data – Cherwell estimates that Oxford students receive on average over 250,000 parcels a year.

My Oxford Year, Their Netflix Cash

This summer, while everyone was busy mocking My Oxford Year or letting their anger out on Oxfess, the Investigations team decided to ask every public authority in town how much they received from Netflix for the shooting of the film. But (surprise surprise), they’re not telling us.

The University took over twice the statutory deadline (20 working days) to get back to us, refusing to disclose the information and claiming it would take them too long to find. Cherwell appealed the decision, with the University’s response being overdue for over a month at the time of writing. Magdalen College also refused to disclose this information, claiming that it would “prejudice [their] commercial interest”, while the Oxfordshire County Council simply did not respond to our request.

The ones that did revealed that the filming was not as lucrative as you might expect: Hertford college made £2,160 renting a room to the production team, and the City Council made £1,365 from filming inside of the Covered Market. Given how abysmal the film was, we’d hope they would have made a little more than that!

You wouldn’t steal a car!

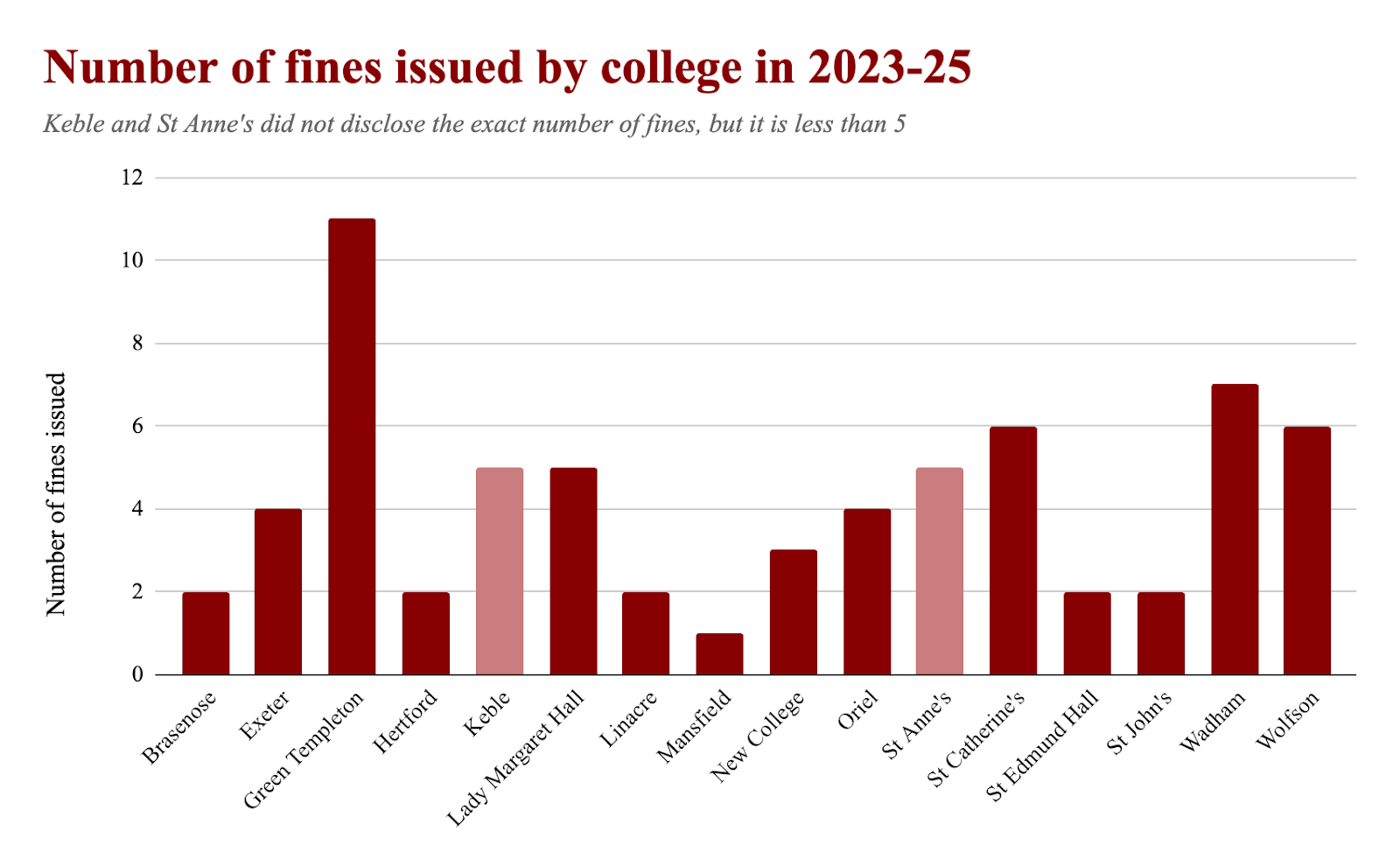

If you weren’t too hungover, you may remember your college Dean or Bursar trying to threaten you during Fresher’s Week with potential fines if you were caught streaming or downloading content illegally on Eduroam. In the spirit of scientific discovery, Cherwell went myth-busting – and we debunked them.

In total, 15 colleges reported issuing fines to students for illegally streaming or downloading copyrighted content on University networks, primarily through torrenting software. This amounted to at least 59 cases over the 2023-25 period. There were no cases of staff being caught doing this – either tutors know how to behave, or they haven’t quite figured out torrenting just yet.

The vast majority of colleges reported less than five instances, with Green Templeton being the clear outlier with 11 cases. One individual at Wadham was found streaming copyrighted content four times within the same year – you’d think they would have learned their lesson the first time around!

The standard fee applied by the University IT services and passed on to students through colleges is £60, though a few colleges add administrative fees, the most expensive being St John’s College at £100. Cherwell understands that no disciplinary action was taken against students for this. With the speed of Eduroam, good luck trying to stream or download anything anyways!

See you in 2026

That’s it from us in 2025! FOIs are at the heart of what Cherwell Investigations does, and we even asked the University how many they receive each year. In 2024, it received 1,093 requests – fully complying with only 566 of them and partially complying with 307. The University did not supply the information for 170 of the requests and did not hold the information for the remaining 50.

Despite the delays, hurdles, and redactions, Cherwell keeps on investigating. With FOIs being one of our main tools to make sense of how decisions are made behind closed doors and to uncover what the University is up to, we will keep on asking, (probably) much to their displeasure.

Regarding Professor Dutta’s appointment, a University spokesperson told Cherwell: “Sexual harassment has no place at Oxford. Our sympathies and thoughts are with anyone who has experienced harassment or misconduct. We strive to ensure that Oxford is always a safe space for all students and staff. We take concerns seriously, applying clear, robust procedures. Support for those affected is a priority, and we take precautionary and/or disciplinary action where justified.

“We reject any suggestion that the University tolerates harassment or does not prioritise people’s safety. While we cannot comment on individual cases, we are committed to continuous improvement and have strengthened our approach over recent years. Our Single Comprehensive Source of Information sets out our approach, support and training. We encourage anyone who has a concern to raise it.”

With special thanks to Amelia Gibbins, Laurence Cooke, and the Cherwell Investigations team for their FOI contributions.

Comparing the Cost of Studying in the UK and the US

Choosing between studying in the UK and the United States goes beyond rankings and course content. Tuition fees, rent, and day-to-day spending add up to an enormous amount. This article examines the real costs of university life in the UK and the US to help prospective students make informed choices based on real life, not stereotypes and false expectations.

How Students Learn to Manage Money Across the Atlantic

People in the UK are raised learning to arrange their budgets carefully. As students, many live with roommates for several years, use the subway, and cook most of their meals at home, not to overpay for dining out.

In the US, student life tends to be more consumption-oriented. Campus culture often includes meal plans, paid activities, sorority and fraternity fees. This can quietly increase monthly expenses.

Tuition Fees in the UK and the US

In the UK, tuition fees are nationally regulated for domestic undergraduate students. In 2025, home students pay a fixed £9,535 ($12,605) per year regardless of subject. For international students, annual fees vary by discipline and institution and typically range from £15,000 ($19,830) to £30,000 ($39,560). Most UK bachelor’s programs are completed in three years.

In the US, average college tuition costs depend on the university type. For this academic year, students attending public in-state universities pay $11,371, while out-of-state students face higher fees of around $25,415. At private universities, the cost of attendance is $44,961 on average. US undergraduate degrees typically require four years of study.

Beyond Tuition: Costs Most Students Overlook

Tuition is only part of the financial picture. Students also face compulsory fees, insurance, books, and academic materials.

In the UK, additional academic expenses usually include:

- Course materials and books: £300–£600 ($400–$800) per year

- Student union and activity fees: £100–£300 ($135–$400) per year

- Field trips or lab fees (if needed, depending on course)

- Healthcare insurance (for international students): £776 ($1,025) per year

In the US, extra costs are often much higher:

- Health insurance: $1,500–$3,000 annually

- Educational materials and access codes: $800–$1,200 annually

- Campus fees and technology charges: $500–$1,500 annually

- Software subscriptions, lab supplies, or accreditation fees: $10,000–$15,000 over 4 years.

Accommodation Costs for Students in the UK and the US

First-year students in the UK usually live in university halls. In 2025, affordable student accommodation starts at around £100 ($132) per week, or £450 ($595) per month; in London, similar accommodation often costs more than £1,100 ($1,455). In the second year, students can move into shared houses for £450 to £750 ($595–$990) per month, excluding utilities.

In the US, living on campus is common, especially in the first two years. The cost of dormitory housing with meal plans is $12,986 per academic year on average. Apartments beyond campus usually cost between $1,200–$1,800 per month in major cities like Boston, New York, or San Francisco.

Day-to-Day Spending

In the UK, a typical student grocery budget is £35–£55 per week ($44–$70), depending on diet and city. Eating out usually costs £8–£13 ($10–$17) per meal. Public transportation is widely used and ranges between £40 and £90 ($50–$115) per month.

US students often spend $60–$90 per week on basic food. Eating out is also more expensive, with even casual meals often costing $15–$25. Transportation expenses range widely according to whether students use cars or local public transportation. In places where transit systems are limited, having a car adds $300–$500 per month.

How Financial Support Shapes Student Life

Most students in the UK are supported by government-backed tuition loans that are repaid only after graduation, once the student’s income reaches a particular level. This approach offers a predictable financial structure. Many typically combine loans with part-time jobs.

In the US, students rely on several sources:

- Federally funded student loans

- Private education loans

- Family contributions

- Scholarships or grants

For day-to-day living, American students are far more likely to resort to credit, following patterns common in their families. If you’re trying to figure out how it actually works, you can find a clear explanation in this comprehensive guide for students managing temporary cash shortfalls.

A Practical Verdict on UK and US Student Expenses

On the surface, the UK may seem cheaper because of tuition costs and shorter degree programs, while the US boasts its worldwide prestige. As a matter of fact, the real cost is shaped by multiple aspects, including the college of choice, location, and the student’s financial habits. In a nutshell, there is no “cheaper” or “better” option. Instead, there is a system that best aligns with a student’s financial circumstances and long-term goals.

Voices from North Korea on escape, language, and belonging

Earlier this year, Cherwell attended Voices from North Korea, an event organised by Freedom Speakers International (FSI), a South Korea-based NGO working with North Korean refugees. Over the course of the evening, I spoke to three defectors – Sujin Kim, Yuna Jung, and Riha Kim – as well as organisers whose work centres on helping refugees rebuild their lives. As three of 30,000 North Korean defectors now living in South Korea, their experiences are not a single story of escape, but a series of unique journeys that complicate how we think about freedom, survival, and belonging.

Journeys of Escape

Yuna Jung left North Korea in 2006. For her, escape began, not at a border, but in front of a television screen. Smuggled South Korean dramas provided insight to a different, better life – contradicting everything she had been taught. She describes them as an “education”; a slow process of unlearning rigid state ideology and imagining a life beyond it. Until then, her future had been clearly mapped out – university, a job as an elementary school teacher, and passing on the same ideology to the next generation. Watching these dramas made her realise this life was no longer for her.

When she decided to leave, she acted with startling directness. The daughter of a military general, Yuna’s status gave her options unavailable to most. She was able to cross the border by asking to be introduced to a military captain as a date – a possibility created by her education, background, and proximity to power.

“I just told him directly that I wanted to escape,” she explains to me. “I didn’t hesitate, just told him, ‘I have money. I can pay. Can you help me?’ and he did.”

Riha Kim, on the other hand, had no wealth, no connections, and no influence to rely on. Instead, she spent several years quietly gathering information, trying to make contacts, and waiting for an opportunity. After several failed attempts, she finally escaped in 2015 through a friend’s house close to the border.

Her decision to leave was shaped by her work as a doctor in North Korea. Again and again, she found herself unable to provide even the most basic, life-saving care. The medicines were simply not available. “It was not right,” she says. She describes being trapped within a system that refused to acknowledge its own failures, even as patients suffered and died in front of her.

Sujin Kim’s story was different again. She defected in 2003, driven by hunger as much as by fear. The picture she paints of life under the regime is brutal; food was so scarce that she was often malnourished from as young as twelve. “Growing up in the regime, I had never really imagined freedom,” Sujin tells me. But desperation eventually inspired imagination: “I couldn’t think of bringing a child into that hardship.”

She paid a broker to help her cross the heavily monitored and deadly Tumen River which separates North Korea from China. What followed, however, was not freedom. Instead, the broker held her in captivity. She tried to escape repeatedly but was caught every time. It was not until 2007 – four years later – that Sujin finally reached South Korea.

Life After Escape

It is easy to imagine escape as a single, defining moment: a border crossed, a door closed behind you. But what I heard repeatedly was that freedom is a far longer process. For most defectors, South Korea brings safety, but not belonging.

A generational divide shapes much of this experience. Older South Koreans, raised on decades of anti-communist education, can be openly hostile. Younger generations, who have only ever known a divided Korea, are less overtly discriminatory – but often indifferent. “They think we are cool,” as Yuna puts it. There is curiosity, but little understanding.

Thomas, a volunteer with FSI, explains how this tension plays out in everyday life. If his South Korean mum knew he was helping defectors, he says, she would be “outraged”. “She actually warns me from time to time that, because I am a chemistry student, the North Koreans might kidnap me or something.” Her fear is sincere, he explains, but it still erects a barrier for people trying to integrate.

Language is one of the most powerful of these barriers. Even though North and South share the Korean language, after 70 years of division there are significant differences in structure, vocabulary and pronunciation. Defectors inevitably stick out. Yuna remembers the day she started to be treated more like a human being: “One day I tried to speak English with foreigners at church, and all of a sudden the treatment was very, very different.” Language, she realised, was not just about communication, but a route to dignity.

This is where Freedom Speakers International aims to help. Founded in 2013 by Casey Lartigue Jr. and Eunkoo Lee, FSI started out as an English tutoring programme. It has since grown into something much larger. To date, FSI has helped more than 600 defectors find their voice and develop confidence through English and public speaking lessons.

For the women I spoke to, FSI has offered more than skills – it has provided a home, a space to reclaim their stories. Sujin describes how transformative this was for her. For years after arriving in South Korea, she focused solely on survival, enduring discrimination, and isolation in a society she had never been prepared for. Learning English and joining FSI became a turning point; she was finally ready to confront what she had lived through.

Casey tells me a similar story about Songmi Han, a refugee with whom he co-authored a book. When Songmi joined FSI in 2019, she was on the verge of suicide. “She was looking for something to save herself,” he says. English became that lifeline. After receiving counseling, she began working part-time at FSI, where the team noticed her extraordinary ability to tell stories.

When Casey suggested turning them into a book, she resisted. “Nobody wants to read my stories,” she told him. “They are too sad.” Eventually, she agreed. “She went from being anonymous in depression to making a real difference in the world,” Casey says. Songmi now describes herself as “one of the puzzle pieces in unification”.

Speaking Out

But speaking out carries real risks. I ask whether encouraging defectors to tell their stories on international stages ever feels dangerous.

Casey tells me about Yeonmi Park, a defector who escaped in 2013 and was later informed that she was number one on North Korea’s target list. He urged her to think carefully. She returned the next day with her answer: she wanted to be so well known that if anything happened to her, the entire world would know.

Riha tells me she is “always scared”. Her family remains in North Korea, and although she was never officially labelled a defector – only a “missing person” – the risk never fully disappears. Still, she is resolute. “If I don’t do this work, then who will speak out?”, she asks. “It is my mission and my responsibility to be a public speaker.”

Another Border: Technology

Listening to these stories, one idea keeps resurfacing. Freedom is never just about crossing a border. It is about being understood, taken seriously, about learning how to exist in a society you were never prepared for. In an increasingly digital world, technology has become yet another barrier to integration.

It felt significant, then, that Voices from North Korea was hosted in the Computer Science faculty. What emerged in discussions was how fundamentally different defectors’ struggles with technology are from those of, say, older generations who find smartphones frustrating. Growing up in near-total technological isolation can make the entire concept of the digital world feel alien.

Before she arrived in South Korea, Yuna had no real understanding of what the internet actually was, beyond what she had glimpsed in South Korean K-dramas. Despite attending university, the only technology she had used was PowerPoint. “I felt very naive about the internet world,” she says. “It gave me a headache all the time because I didn’t understand it.”

Sujin recalls attending an education centre in Seoul and spending hours simply learning how to type – something Yuna, with access to university computers, had at least encountered before.

More broadly, the defectors described challenges not only with digital skills but the concept of digital identity itself. For many, the idea of an online account, or personal digital space that belongs to you, is deeply disorienting. Hayoun Noh, the event organiser, is a PhD candidate in the Human-Centred AI group in the Department of Computer Science. Her research explores the intersection of technology and mental health, and how digital tools might be better designed for North Korean defectors.

Her research has shaped how she thinks about technology in all our lives. “One thing that has really shocked me is how toxic social media is for them,” she tells me. “We all know what it feels like to scroll down Instagram and feel sh*t about yourself. But when these defectors told me they would be browsing Instagram and seeing all these luxurious lives of South Koreans, I wondered if they would ever be able to achieve this level of happiness.”

“For many, the concept that social media is not a mirror of reality is entirely new. It really makes you wonder if we just got used to all the lies?… because we are so desensitised to all these superficial lives,” Hayoun reflects.

These challenges sit within a deeply troubling context. South Korea has the second-highest suicide rate, and for people aged 10-39, suicide is the leading cause of death. For North Korean defectors, discrimination, isolation, and lack of access to support intensify an already severe crisis.

Hayoun explains why she shifted her research focus: “I got to know that actually even the concept of mental health is a privilege…. Many people who are extremely vulnerable and marginalised do not even have the access to doctors or medication…. As a South Korean myself, I had always been aware of the difficult stories of North Korean defectors. I wanted to focus on this quite extreme case where people do not have an awareness of mental health, questioning who is actually systematically excluded help?”.

What Voices from North Korea made clear is that freedom is not a single moment, but a series of border crossings – physical, linguistic, social, and digital. Crossing one does not guarantee passage through the next. But for the women I met, speaking out remains both an act of resistance and a way forward.

Vice-Chancellor’s pay package rises to £666,000, among highest paid in Russell Group

The University of Oxford’s Vice-Chancellor, Professor Irene Tracey, received a total pay package of £666,000 this year, the University’s latest accounts reveal. This represents a 2.5% increase in her base salary, placing her as one of the highest paid Vice-Chancellors across Russell Group universities.

Tracey’s pay package also included £188,000 for accommodation, and £51,000 in lieu of pension contributions. The Vice-Chancellor currently lives in accommodation provided by the University valued at £3.5 million, and therefore does not pay rent.

Cherwell understands that the Vice-Chancellor is required to reside in a property “appropriate for undertaking University duties”, but that she decided to purchase her own property upon taking the role. She has been living in temporary University-owned accommodation since accepting the role, but will move into her new property in January 2026.

The University told Cherwell: “The Vice-Chancellor’s total remuneration for 2024/25 includes an unusually high payment of £91,460, as part reimbursement for tax liabilities.” It said the charge arose while Tracey was living in temporary accommodation, which constituted a taxable benefit, including a £49,762 payment relating to the previous financial year which will not apply after January 2026.

The £666,000 total package makes Tracey one of the highest paid Vice-Chancellors in the country. Her Cambridge counterpart, who was previously the highest paid in the Russell Group, received £507,000 in 2025, while the Vice-Chancellor of LSE was paid £530,000.

Only the Dean of London Business School, which is not part of the Russell Group, received a bigger package of £707,000. Many Vice-Chancellors across the country also received exceptional bonuses, ranging between £5,000 and £50,000.

Jo Grady, general secretary of the University and College Union, told The Times Higher Education: “Vice-chancellor salaries are already eye-wateringly high; this Christmas they should do the charitable thing and donate their bonuses to the food banks that will be supporting far too many students.”

In Oxford, eight other senior figures were paid £300,000 or more in 2025 – over £655,000 for the highest paid. In total, 470 employees were on annual salaries of £100,000 or more, including 113 clinical staff.

When taking up the post in January 2023, Tracey declined a proposed 8.4% increase in her base salary “in light of the financial situation”, a University spokesperson told Cherwell. According to the University, before this 2.5% raise, “the base salary for the role had not increased since 2009”.

The pay of the Vice-Chancellor and of other senior University figures is decided by the Senior Remmuneration Committee, which includes external members and makes recommendations regarding salaries every two years. The University emphasised to Cherwell that Tracey “does not participate in any Council discussion regarding her own remuneration”.

A University spokesperson emphasised to Cherwell that “in leading the world’s highest-ranked university, the role of the Oxford Vice-Chancellor is complex, demanding and multi-faceted”, and that the increase in her pay package was granted “in light of these responsibilities and taking into account the current Vice-Chancellor’s performance and experience, as well as the market rate in UK universities for jobs of comparable scale”.

Oxford Town Hall flies Palestine flag for Ramallah Mayor visit

Oxford City Council flew the flag of Palestine from the Town Hall last week to mark an official visit from the Mayor of Ramallah Issa Kassis. During the visit last Tuesday, Mayor Kassis met with Oxford’s Lord Mayor, Councillor Louise Upton, and City Council Leader Councillor Susan Brown. The Palestinian Ambassador Husam Zomlot, who went to university near Ramallah, was also in attendance.

Ramallah, a city in the central West Bank, has been twinned with Oxford since 2019. Members of the Oxford Ramallah Friendship Association (ORFA), which campaigned for 17 years to twin the two cities, invited Mayor Kassis to a committee meeting in the course of his visit. ORFA co-ordinates youth exchanges, educational visits, and trade union collaboration between the cities, among other ties.

Mayor Kassis said: “We are truly grateful for the historic friendship and partnership between Ramallah and Oxford, grounded in mutual respect and solidarity. It was an honor to visit Oxford and strengthen the ties between our cities and explore how we may continue working together in the spirit of solidarity and shared values.”

Mayor Kassis also met with local faith groups and councillors at the Rose Hill Community Centre, which displayed the Ramallah Municipality flag to mark the occasion.

An ORFA spokesperson told Cherwell: “We were very pleased to partner with Oxford City Council in welcoming Mayor Issa Kassis to Oxford this week. Over 60 people attended a celebratory reception at Rose Hill Community Centre.

“Civic events of this type are invaluable in developing supportive bonds between our cities. We hope that Oxford can be a beacon for the promotion of mutual understanding, solidarity and cooperation between UK [sic.] and Palestine.”

Councillor Louise Upton, Oxford’s Lord Mayor, said: “It was a pleasure to welcome the Mayor of Ramallah to Oxford. Our two cities share a long history of friendship, formalised when we became twin cities in 2019. This visit was an important opportunity to reaffirm our connection and explore new ways to work together at a challenging time in Palestine’s history.”

Oxford City Council has passed a number of motions in support of Palestine in recent years. This March, the Council passed a motion in support of the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) movement. Inspired by the movement against South African apartheid, BDS aims to challenge “international support for Israeli apartheid and settler-colonialism”.

Worcester College Provost made Labour peer in the House of Lords

Worcester College Provost David Isaac has been appointed to the House of Lords as a Labour peer. He is among 34 new peerages created by Prime Minister Sir Keir Starmer, 25 of which are Labour, 5 Liberal Democrats, and 3 Conservatives.

Isaac has been Provost of Worcester College since 2021. He was previously chair of Stonewall, beginning in 2003, a UK human rights charity advocating for LGBTQ+ equality. Under his leadership, the group successfully lobbied for the abolition of Section 28 of the Local Government Act 1988, which had restricted the visibility of homosexuality in public life, and for the introduction of civil partnerships in 2004.

Isaac also chaired the Equality and Human Rights Commission from 2016 to 2020. During his tenure, the Commission dealt with issues surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic, Brexit, Windrush, Grenfell Tower, immigration policies, and allegations of antisemitism in the Labour Party.

In a statement to the press, Isaac said: “It is an honour to have been appointed to the House of Lords, and I’m grateful to the Prime Minister for the opportunity to make this contribution to public service in parallel with my commitment to Worcester College, Oxford.”

Isaac studied Law at Trinity College, Cambridge before completing an MA in Socio-Legal studies at Wolfson College, Oxford. As well as being head of Worcester, Isaac is the Chair of the University of Arts London and Chair of the Henry Moore Foundation, a UK-based arts charity. He is also the first Provost to keep bees at Worcester and occasionally sells their honey around college.

Among those joining Isaac in the Lords will be Matthew Doyle, a former 10 Downing Street Director of Communications, and Richard Walker, CEO of Iceland Foods. Isaac is not the only new peer with a background in education. University of Surrey Pro Chancellor, Dame Anne Limb, and University of Exeter Chancellor Sir Michael Barber also received peerages, alongside other academics.

The House of Lords is the UK’s unelected upper chamber of Parliament, composed of mostly life peers alongside a smaller number of hereditary members. Life peers are appointed from a broad range of professional and public backgrounds and use their expertise to scrutinise policy and conduct in-depth inquiries through committees. They also receive a £371 daily allowance on top of income from their other positions.

Following the new peerages, and along with the planned abolition of hereditary peers, Labour will increase its representation in the Lords from around 25% to 30% by the end of the year. This comes amid growing frustration within the party over delays to government legislation in the House of Lords, such as the Employment Rights Bill, in which ministers were forced to make some concessions.