Walking down Broad Street can sometimes resemble a school register. It would, admittedly, be a strange class that comprised Thomas Bodley, the Weston family, the first Earl of Clarendon, and Gilbert Sheldon. But Oxford’s avenues are littered with the names of its donors, on libraries, museums, and faculties. Such a privilege is anything but cheap. Julian Blackwell’s £5 million donation to the Weston Library gave him a hall. For naming rights to a whole building, you’d be looking at something closer to the Weston family’s donation of £25 million.

Carving your name into the fabric of Oxford is undoubtedly a tempting idea. Initials can be found carved into stone, into pews, into walls, by students responding to just this. It’s catnip to donors. Universities are not cheap to run, and expansion is even more expensive. Combining the two ideas, using the allure of naming rights to secure funding for the University’s future, is inevitable.

A donor is inextricably linked to Oxford when a building is given their name, with their involvement discernible just from looking at a map of the city. It associates the donor with education and philanthropy – noble aims that can be exploited into ‘reputation laundering’. Furthermore, it represents trust in the family in question, not just at the time of the donation, but for as long as the building stands. This might be centuries. As a result, named buildings pose huge potential liabilities to the credibility of the University by cementing a legacy on the security of little more than money.

These risks are not theoretical. It took me two years to actually work out where the Art, Archaeology, and Ancient World Library was. Everyone I spoke to going in that direction still called it the Sackler.

In the wake of the Sackler support scandal, Oxford has not resiled from naming buildings after the biggest contributors. The Schwarzman Centre, opened earlier this month, was the result of the largest donation received by the University since the Renaissance. High-level donors receive other tangible benefits, including regular communications with the Vice Chancellor, and contact with the Chancellor and other senior levels of the University. Allowing them to stamp their names onto the city with no more than a bank statement connecting them to Oxford risks rendering the city a playground for the vanity of the rich. Are the benefits of this money worth it?

Bodley and Sheldon

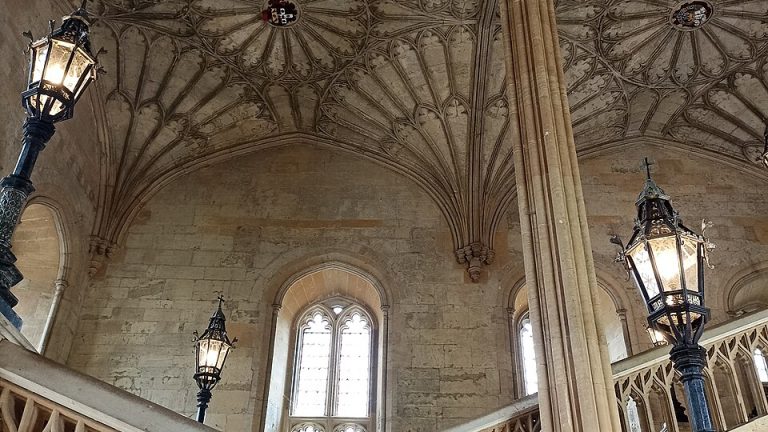

The Old Bodleian Library, the oldest named University building in Oxford, actually bucks this trend. It is named after Thomas Bodley, who was instrumental in reviving the library after the Reformation. Previously, Oxford’s only library had been housed in Divinity Schools. This collection of religious tracts did not fare well in the 16th century – the Dean of Christ Church removed all of its “superstitious books and images” in 1550. Bodley, a fellow of Merton College, devoted his retirement to refurbishing the building and donating some of the 2,500 books contained on its 1602 reopening. He also took the first steps towards making the Bodleian a legal deposit library, striking an agreement with the Stationers’ Hall that they would send the Bodleian a copy of every book registered to their hall. Operationally, the Bodleian would not exist in the form we currently see without Bodley. He also contributed financially, largely with the money received from marriage to a wealthy widow.

Gilbert Sheldon, who paid the full cost of Sheldonian construction, was also Warden of All Souls, Chancellor of the University, and had to be physically ejected from All Souls by Parliamentarians during the English Civil War. While his involvement was more financial than operational, he was closely connected to Oxford. The Sheldonian marks both his money and his effort, and provides a connection to Oxford’s history. The building is richer for its association with Sheldon – more closely integrated into the heritage of the city.

Keep it in the family

John Radcliffe, who provided £40,000 for the construction of the Radcliffe Camera in 1714, gave the money in his will on the condition that construction would not begin until he and his sisters had all died. Clearly, he had an eye for a legacy, but this was a legacy he did not wish to realise during his life. In fact, he appeared to want no part of his generation to see his library. When the Radcliffe Library (as it was then known) was built, it therefore appeared less a personal project, and more a donation to the future of science. A board of trustees still manage Radcliffe’s testament today.

However, giving your name to a building puts a more metaphorical trust in every subsequent generation of the family. In 1884, Augustus Pitt Rivers gave over 20,000 archaeological artefacts to the University, which became the founding collection of the Pitt Rivers Museum. By all accounts, he was devoted to the subject, with a focus on scientific archaeology, and on cataloguing everything, not just aesthetically-pleasing pieces, which changed the way museums and excavations were viewed. Fifty-six years later, Pitt Rivers and Oxford were linked once more. This occurred when Augustus’ grandson, George Pitt Rivers, requested in 1940 that, if he had to be interned for his support of Oswald Mosley, he would prefer for it to be at Worcester College. It was this Pitt Rivers who gave the skull-cup used by the Worcester SCR until 2015, which had itself come from his grandfather’s private collection.

This unfortunate connection did not impact the Pitt Rivers Museum at the time, but the more recent revelations risk undermining the work that it has done to move away from its colonial legacy. It’s worth noting that the Pitt Rivers family, while always linked to ethnography, has approached it in very different ways depending on the generation. Julian Pitt Rivers, George’s son, was a vocal supporter of cultural diversity, in sharp contrast to his eugenicist father. The problem is that, by tying the building and the work of the museum to a single family, its work is forever linked to their lives and their interests. When attempting to move away from some aspects of ethnography and archaeology, particularly concerning human remains, it is difficult to remain named after a man who collected so many of them.

The Art, Archaeological, and Ancient History Library (neé Sackler)

One of Thomas Bodley’s innovations had been a Register of Donors, allowing names of donors to be publicly displayed. A successor to this, the Clarendon Arch, carries on this legacy, bearing the names of the most significant benefactors of the University. This arch is one of the only places where the Sackler family are still present in Oxford. In a statement released in 2023, the University removed the pharmaceutical dynasty’s name from a gallery, a fellowship, and a library. This was four years after the first institutions had started to ‘de-Sackler’ their buildings, and a year after Purdue Pharma settled their suit from US states alleging that they fuelled the opioid crisis.

Treatment of donors is increasingly systematised and incentivised. The Development Office’s page highlights the perks of giving. The very first option is “naming opportunities”. Then, the Vice-Chancellor’s Circle provides “regular communications from the Vice-Chancellor” as well as an annual members’ event. The Vice Chancellor’s Guild gives you this, as well as an annual dinner in Oxford. The highest circle is the Chancellor’s Court of Benefactors, meeting twice a year in Oxford and London. The description highlights the “chance to engage with the Chancellor, Vice-Chancellor, and other senior leaders within the collegiate University” to help develop “a greater understanding of the life and work of the University and the colleges”.

The approach taken appears to move away from naming opportunities as recognition for work done within the University. Instead, it encourages specifically external figures, dangling the chance of networking with senior figures in exchange for donations. The more you give, the more access you receive. A month after the Purdue Pharma settlement, Theresa Sackler (a member of the Chancellor’s Court) was invited to a private screening of the Boat Race on board the Erasmus, an event attended by both the Vice Chancellor and the Chancellor.

A close relationship to donors makes their support more likely. However, it also becomes more difficult to sever ties. With the level of personal connection given to modern donors, there may be reluctance to completely cut off those who have gone awry. While disgraced donors can use the University’s name for a semblance of credibility, the University is pulled into the scandal, and suffers reputational damage as a result. Providing access to the extent that the Chancellor’s Court does, and tying the University to its largest donors, relies on the donors themselves being truly benevolent. The Sacklers are a key example of the naivety of such a belief.

The future of donations

But running a university is only becoming more expensive. With lower levels of government support, and capped tuition fees for domestic students, universities have to find some way of funding expansions. Advances in technology, increasing student numbers, and environmental priorities all point towards building more. If putting a donor’s name on a wall ensures that their £185 billion can help make study of the humanities more accessible, then what’s wrong with that?

The recently-opened Schwarzman Centre is an example of this continued practice. Stephen Schwarzman did not attend Oxford. The co-founder of Blackstone, Schwarzman has donated to institutions including the New York Public Library, the Tsinghua University, and MIT. His asset management firm, the largest commercial landlord in history, has been accused by a United Nations adviser of helping to fuel the global housing crisis. The firm denies these allegations, and say that they are based on “factual errors and inaccurate conclusions”.

The Schwarzmann Centre for the Humanities is certainly a boon for the University. It helps bring Oxford closer to its sustainability goals, and puts seven faculties under one roof, promoting interdisciplinary cooperation. Its concert spaces are accessible and support the arts at a time when government funding is extremely limited. Its AI Institute could help analyse and solve the problems faced by the emerging technology. But something does ring hollow about using money raised in sky-high rents and gentrification to investigate the problems of the future. It helps the University, and it helps humanity. But it does very little for those suffering right now.

It all comes down to priorities. Is it more important that the centre of Oxford feels linked to the University’s rich history, and celebrates the people who worked hard to make it the place it is, or is it more important that it continues to expand and adapt quickly, even if this means appending names that have little business inside the city outside dinner galas? This is certainly not to discourage charitable giving. Still, there is a certain vanity in philanthropy that does not consider the positive results of their gift a sufficient reward. When naming a building entails trusting that the family name never falls into disrepute, and that the University will be able to handle it if it does, perhaps it would be better not to use billionaires who made their money from pharmaceuticals or private equity as namesakes.