In Skyfall, the Bond franchise’s 50th anniversary film, the passing-prime protagonist sits alone in Room 34 of the National Gallery. In a moment of reflection as he waits to meet the young and tech-savvy new Q, he gazes at Turner’s The Fighting Temeraire. Though unacknowledged, there is a quiet camaraderie between him and that “bloody big ship”.

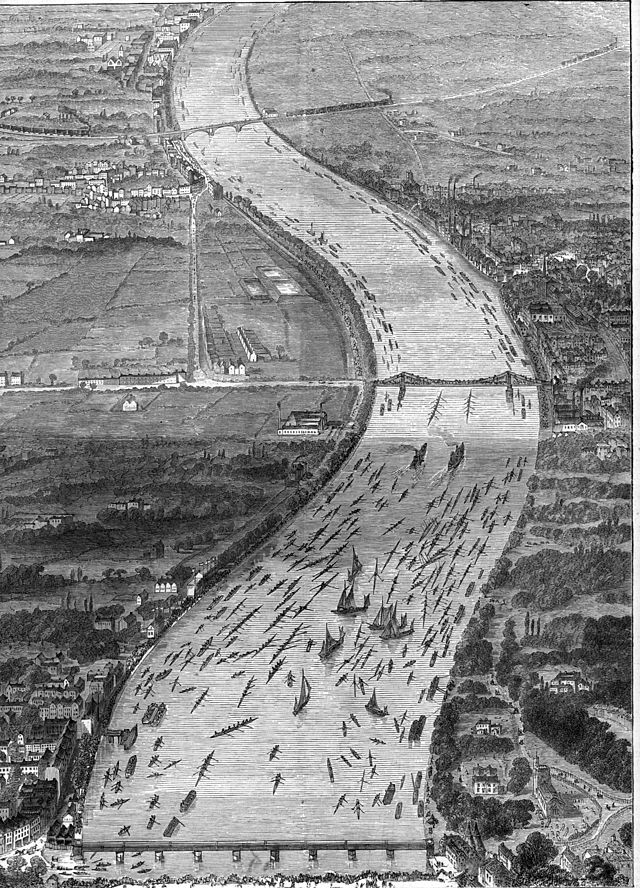

Turner’s painting invites viewers to evaluate the nature of modernisation, and to question what role rusty battleships and dusty institutions have in an ever-changing Britain. At this milestone in the National Gallery’s life, marking 200 years, we reflect with Turner’s honey-hazed nostalgia on what this great British institution means to us today. The gallery was established in 1824: 38 paintings and an address of No.100 Pall Mall. Two centuries later, it is home to 2,300 works, host to over 4 millions visitors a year, and at the heart of the nation in Trafalgar Square, it is far from being towed to the scrap yard.

To me, the National Gallery’s appeal lies in part in its name and founding ethos; unlike most European national collections, the gallery was not the product of the nationalisation of the royal collection. Rather, it was established through Parliament on behalf of the British public, with whom ownership still resides today.

The British public have been actively involved ever since: the gallery’s collection has been stabbed, stolen, shot, and – most recently – souped. Velázquez’s Rokeby Venus has been attacked in protests divided by over a century, while the only successful art heist (a Goya, burgled 1961) resulted in a high profile trial. Kempton Bunton, bus driver turned art thief, was found not-guilty of stealing the painting – but guilty of stealing the frame.

It is not just the vandals that make the National Gallery ours, but the visitors. As a small child, the National Gallery was a soggy Saturday sanctuary to me, traipsed through on many a rainy weekend, hand in hand with my art-loving dad. Over a decade later, long after my family had moved out of London, I would catch the train into the city and pay a pilgrimage back to the National Gallery, which became my school each saturday. The gallery hosted my education for two years during sixth form, in collaboration with Art History Link-Up.

AHLU is an educational charity which provides free A-Level and EPQ instruction for state school students. Currently only 8 state schools throughout the UK offer art history. Yet since AHLU was founded in 2016, 400 young people across 200 schools have had the opportunity to study the subject, including myself. The National Gallery is a stunning place to study. While the gallery provided a classroom, my favourite hours were spent wandering through the collection. Huddled around paintings, we would discuss Caravaggio’s chiaroscuro and I would try to capture something of its effect through inked words and blurry sketches in my notebook’s margins.

The collaboration with AHLU demonstrates the ideals of outreach and inclusion that make institutions such as the National Gallery enduringly vital in modern Britain. In a country that has yet to foster comprehensive cultural accessibility, having nationally-owned, publicly accessible art galleries is an investment in the idea that the nation’s treasures, that culture and education, are everyone’s to share in.

And while I came to love Turner’s great visions of national change, it is Rembrandt’s wistful self-portraiture of ageing that captures me most. His gentle brushwork and tender observation in A Woman bathing in a Stream impressed on me the significance of the personal, of the insignificant people that mean the most. The National Gallery is an institution built from the people of this country, and it seems to understand that. Though it has been suggested that Rembrandt’s painting was simply a study for a larger biblical work, the National Gallery believes that ‘the most likely possibility is that Rembrandt knew and loved this quiet, gently absorbed woman and shared her delight in an unguarded moment of pleasure in some anonymous Dutch stream’.

![‘warþ gasric grorn, þær he on greut giswom’ [Fish sad when washed to shore] – The Franks Casket ‘warþ gasric grorn, þær he on greut giswom’ [Fish sad when washed to shore] – The Franks Casket](https://cherwell.org/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/article_topimage_Franks_Casket_rear-768x291.jpg)