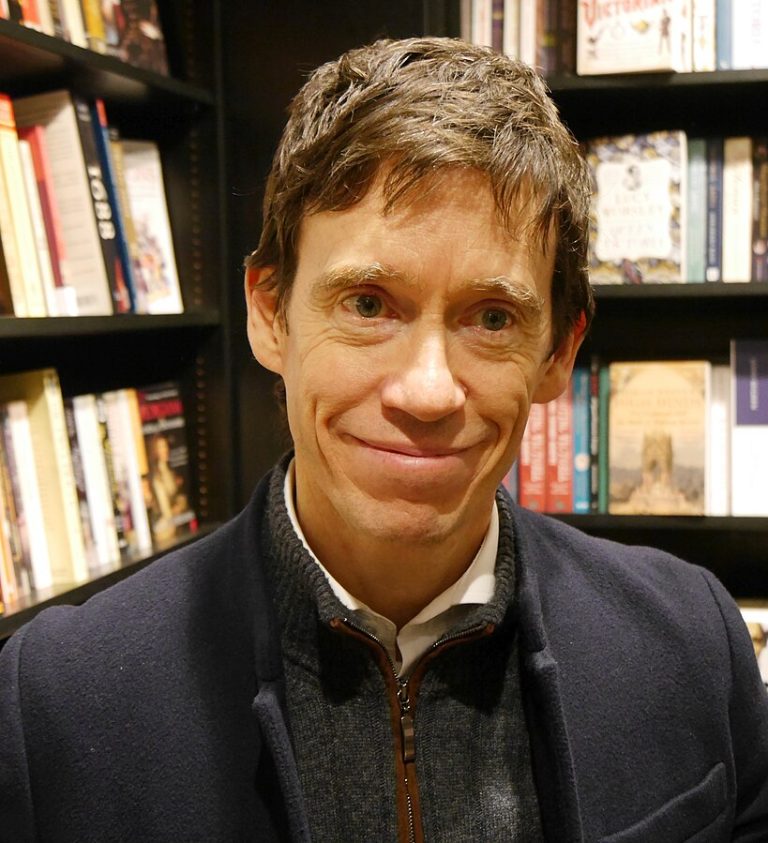

This is a marvellous book, a memoir of Rory Stewart’s nine years in Parliament, and its greatest flaw is that it is not long enough. The original draft was 220,000 words long, and included chapters on Yemen, Libya, Covid policy, populism, and ethics in politics, all of which have now been cut. What remains is nonetheless a work of rare and great power. Stewart writes graceful and lucid prose, and his gifts for simile and character suggest that we lost a novelist where we gained a diplomat, professor, podcaster, and politician. He also possesses the novelist’s skill for showing rather than telling, and at a time when there are so many books telling us what is wrong with Parliament or why the Conservatives were such a mess, this candid firsthand account of the years 2010-19 is invaluable.

By conventional measures, Stewart’s political career was a failure. He did not become Prime Minister; he never held a Great Office of State. But a glance at his record in the offices he did hold – Minister of State for Prisons, for instance – reveals a deeply committed man with the ability to tackle huge problems when given the manoeuvring-room to do so. Some of the greatest politicians, moreover, transcend the posts they hold, and are remembered hundreds of years after the more conventionally successful ones have been forgotten (compare the reputations of Edmund Burke and Augustus FitzRoy). Stewart will be remembered as one of the greats, and the strength of his writing and intellect are such that historians of the future will use this book as a resource, certainly more than they will use, say, Ten Years to Save the West.

One of his gifts is for perceptive character sketches. Nearly every politician of note is observed here at close quarters and is shown to be comic and grotesque. David Cameron, with his pink cheeks and breezy ignorance, is a harbinger that “the party of Winston Churchill was becoming the party of Bertie Wooster”. Of Boris Johnson, the book’s great antagonist, nobody has ever produced a better physical description:

“His hair seemed to have become less tidy, and his cheeks redder… as though he was turning into an eighteenth-century squire, fond of long nights at the piquet table at White’s. This air of roguish solidarity, however, was undermined by the furtive cunning of his eyes, which made it seem as though an alien creature had possessed his reassuring body, and was squinting out of the sockets.”

Stewart foresaw in 2019 that Johnson would “rip the Conservative Party into pieces, unleash the most sinister instincts of the Tory right, and pitch Britain into a virtual civil war”. The pair’s final confrontation over the keys to No. 10 is presented here a tad too theatrically considering that it was only a BBC debate, but this is forgivable because, undeniably, Stewart was right. The last five years and, by extension, the next twenty, would be very different if he instead of Johnson had become Prime Minister.

As I say, Politics on the Edge is a book that shows rather than tells, and it allows us to infer for ourselves what is wrong with the modern structure of politics. We must be careful not to over-generalise from the experiences of one man, and it should be noted that Stewart neither gives any solutions to the biggest problems he describes nor sets forth anything like an ideology; but as far as I can make out, some of the most pressing issues that he raises are the following:

The selection system for parliamentary candidates – This is utterly dysfunctional, favouring a very specific kind of party loyalty rather than actual talent; it was due largely to luck that Stewart slipped in through the cracks and got himself elected.

The toxicity of Parliament – Stewart describes “more impotence, suspicion, envy, resentment, claustrophobia and Shadenfreude than I had seen in any other profession.”

Psychological effects on MPs – When a released prisoner ends up committing rape and murder, it is the Minister for Prisons who must face the grieving families and accept official responsibility. In the case of the family of a manslaughter victim, he must also carry out the horrible duty of explaining why the offence cannot be punished as murder. These are only two examples of episodes that could be psychologically scarring, and Stewart discusses them openly and sincerely.

Pleasing the press – Stewart and other MPs who make the tiniest errors or misspeaks must put up with abuse and misconstructions from keyboard warriors and press across the country. Politicians have always had to put up with the sneers of a hostile press, but nowadays publicity has been prioritised over policy to a quite unprecedented extent. Policies are chosen less and less for the sake of their own merits, and more and more for the sake of pleasing the tabloids and opinion polls. Stewart also admits that some policies can only be carried out by certain parties: only the Tories, for instance, can push through sentence-reduction laws which coming from a Labour government would have been attacked by the media as “soft on crime”.

The party line – For the most part, MPs must dance to the party whip. Realism and intellectual honesty are very difficult under a party system. On the passage of legislation, Stewart writes: “Even the most rebellious MPs, famous for their obstreperousness, voted against the government in perhaps only five votes out of a hundred. All of which raised certain questions about the theory that MPs were independent legislators, carefully scrutinising laws.”

Talent blockage – With ministerial appointments, such things as talent, enthusiasm, and expertise seem practically unheard of. Having applied for a position on a committee that he was passionate about, Stewart was refused because “the whips had apparently been told to exclude anyone with an interest in a subject from a bill committee, for fear they would ask awkward questions.”

Sheer powerlessness – This, perhaps, is the most problematic of all. Much of Stewart’s growing desperation is at how ideas are stifled and no fundamental change can be enacted, owing to the mental bankruptcy of ministers, an immovable civil service, directors-general who can block any initiative, and other practical constraints such as time. “Every day made me more and more conscious of how difficult it was to achieve any fundamental change.”

***

There is one more thing which in a book of this kind is essential. Beyond style, observations, and characters, the most important quality of a memoir is the personality of the author. It should shine through on every page. It should leave a lasting impression afterwards. It should be the one element which above all makes the book worth reading. Politics on the Edge meets all these criteria. Stewart is thoughtful, compassionate, and honest, with an eye for detail and a mind for solutions in government. In a Parliament and more specifically a party filled with hundreds of bleating robots, he is a free intelligence, with a rich appreciation of the arts, nature, history, tradition, and cultures. He is an anachronism, not in the cartoonish sense, but because if he were referred to as a “right honourable gentleman”, it would be a fact rather than an appellation. No other modern politician could say without irony that he believes in love of country, respect for tradition, prudence at home, and restraint abroad, or could give a speech containing the line that “True courage is not the opposite of cowardice, but the golden mean, between cowardice and foolhardiness.” Had he been born a century and a half earlier, Stewart might have been remembered as one of the great Victorian statesmen, a Prime Minister or a Viceroy, as well as a man of letters. As it is, however, he entered the politics of an age which punishes courage and rewards stupidity, and he must join Butler, Gaitskell, and Jenkins as one of the great prime ministers we never had.