It was the third time I’d walked past the Rad Cam noticeboard before I finally stopped. I had assumed it was just another poster, lost in the usual blur of student plays, society termcards, and talks promising free pizza. But this one was oddly specific. It advertised a Hamlet performance staged in 2011 at a venue called “The Echo Chamber”. The font was formal, the layout carefully designed – it all felt familiar enough to pass at a glance. Yet at the bottom were the elaborate crests of “Creech College” and the “University of Kingswell”. Neither of them rang a bell.

A few days later I spotted another at the Old Bod, wedged between notices about library rules and history databases. This time it advertised a conference on “The Air Battle of Pearl Harbor at 70: New Archival Discoveries,” held in 2011 at “Casaubon College” – part of the University of Kingswell. A quick Google search confirmed that none of these places existed.

The same week, I found myself staring at one of the large plywood boards along Catte Street, trying to make sense of it. It announced – in serifed capitals with a Latin feel – “A classical ritual in the Greco-Roman tradition celebrating the late Sir Francis Bowell, holder of the Mould Chair of Greek at the College of Casaubon” in 2011. A coda specified: “The ceremony will include a sacrifice and libations.”

Intrigued, I began asking around – had anyone else seen the Kingswell posters? At first, no one had. Yet once my friends noticed one, they seemed to appear everywhere. All of the posters had something else in common: a QR code printed at the bottom, leading to a sparse Linktree page. It contained neither names nor explanations, simply a downloadable PDF titled Dust on Marble.

It turned out to contain the opening chapters of an anonymous satirical novel set in 2011 in an Oxford-like university town, complete with exaggerated traditions, obscure societies, and a narrator with a sharp eye for class divides and academic absurdities. The writing was surprisingly polished – more deliberate than one would expect from a casual student prank – which only added to the peculiarity.

The website offered the option to subscribe to a newsletter. Expecting little more than a confirmation email, I signed up. Over the following weeks, I received short messages with cryptic updates about the project, such as “Oscar Wilde has acquired the cockerel. Wigs are encouraged in the evening”. They were signed by the “Sovereign Sesquipedalian Fissiparous Order of Saint Gwinnodock of Bethlehem, of Sparta, and of Atlantis”.

At first I assumed it must be a group of students, perhaps an art project or an elaborate in-joke, but the longer it went on, the less certain I became. There were no society references, no Instagram accounts, and no familiar names circulating. It all felt less like a prank and more like a carefully constructed world that had quietly appeared in the middle of Oxford. The more I read, the more the posters began to feel like part of the story itself – the fictional colleges and libation ritual featured in the novel, as though the city had been folded into the fiction.

One morning, I woke up to a subscription email mentioning that a “reading” of the latest chapter was taking place “all day” at “Vaclav Havel’s bench” in Uni Parks. It wasn’t framed as an event – there was no specific time and no invitation to meet anyone. Yet the location was real. It was an art installation devoted to the memory of the Czech human rights advocate, easily found on Google Maps.

When I decided that curiosity was more important than deadlines and went to investigate, I wasn’t sure what to expect. Online images suggested a small, round table built around a tree, flanked by a couple of elaborate chairs. It felt strangely natural to find about a dozen carefully designed booklets lying in a neat pile. Their shiny covers resembled marble, and the title was printed as if formed from dark, scattered dust. On the second page, a sentence read: “This edition is limited to 250 numbered copies.”

I sat down and skimmed through the new chapters, enjoying the rare sunshine. It turned out I was not the only one intrigued. During the hour or so that I spent there, three students showed up who were following the same trail. Two had also seen the posters, and one had received a printed copy in an anonymous envelope left in their pigeonhole, with no further message. We briefly talked about our puzzlement, each of us quietly wondering whether any of the others might be the author.

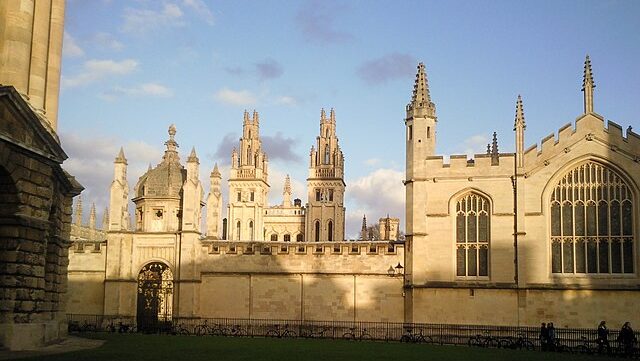

No newsletter updates followed until a digital version of the new chapters was sent on Christmas Eve. Since then, emails have fallen silent, and the posters have been removed. To my knowledge, only two plywood boards remain, both on Catte Street – one by the University Church and one by the Old Bod.

If the goal was notoriety, the attempt has failed. The only result returned by Google is a puzzled Oxfess post from October. But part of what makes the whole episode so alluring is how naturally it fits into Oxford life. This is a city that thrives on stories – on whispered traditions, obscure societies, and half-true legends passed down between generations of students. From secret dining clubs to elaborate pranks that become part of college lore, Oxford has long blurred the line between institutional seriousness and playful myth-making.

The Kingswell posters felt like a modern extension of that tradition. They didn’t announce themselves as art or performance. They simply existed – quietly strange, half-believable, and left for students to interpret. In a university defined by names, titles, and achievements, the idea of a creator choosing to remain invisible feels almost rebellious. The mystery becomes part of the work itself. It also speaks to a certain hunger for novelty within the routines of academic life. Between lectures, essays, and problem sets, it’s easy for days to blur into one another. The sudden appearance of something unexplained offers a small disruption, a moment of intrigue in an otherwise predictable landscape.

The content of Dust on Marble mirrors this fascination with hidden worlds. Its exaggerated societies, ceremonial rituals, and obsessive hierarchies feel like satirical versions of the very myths Oxford students joke about.

Sometimes I have to go through the photos I took of the posters, or touch the booklet, just to reassure myself it wasn’t all a feverish dream. When clarity returns, I am left wondering whether this mystery exists only for the present moment – asking nothing of its audience except fleeting curiosity – or whether it is part of something more intricate, with a hidden purpose still to be revealed. Only time will tell.