Rifling through the filing cabinet of successful prequels, we might find such works as Shakespeare’s Richard II and Henry IV—either of which I would choose to see over his original Henry VI trilogy—or Rhys’ Wide Sargasso Sea, which serves as a post-colonial answer to Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre.

But of course, the term is more often associated with the infamous Star Wars prequels, which are now widely scorned, and branded a disgrace to a venerable cinematic universe.

Coming off the back of Breaking Bad, arguably the greatest television drama ever to have been broadcast, the arrival of Better Call Saul, whose third series began last week, was a source of both excitement and apprehension.

The dilemma faced by a Breaking Bad prequel, despite the uniqueness of its predecessor, is generic enough: how do you offer viewers the opportunity to reconnect with the world and characters of the original series while ensuring that the prequel does not itself descend into vacuous, self-indulgent fan service, cynically milking the popularity of the parent programme?

Better Call Saul holds onto many of the signature stylistic elements of the original, including extensive use of flashbacks and flash-forwards, elaborate montages and symbolic music choices. Visually, however, the difference is striking: the colours and shots are generally far brighter, the sets and locations look cleaner, even glossier. Where Breaking Bad dealt in grit and grime, Better Call Saul deals in flamboyance and sparkle.

This is because the visual style of each show reflects the outlook of its central character. The very first scene of Better Call Saul, for instance, introduces us to Saul’s life after the events of Breaking Bad, in which he has become a low-level manager at a fast-food restaurant. At one point, he becomes afraid that he may have been recognised, his disguise blown. Crisis averted, he returns home and reflects upon his life before Walter White sent the entire thing careering off course.

The beauty of the scene exists not only in its nod towards continuity (Saul had joked about becoming “manager of a Cinnabon” in Breaking Bad) but also in the contrast with what came before. The viewer is jarred by the sheer banality of Saul’s life after the Earth-shattering drama that characterised Breaking Bad’s final episodes. The events that precede that series will also provide a stark contrast, albeit in a very different way.

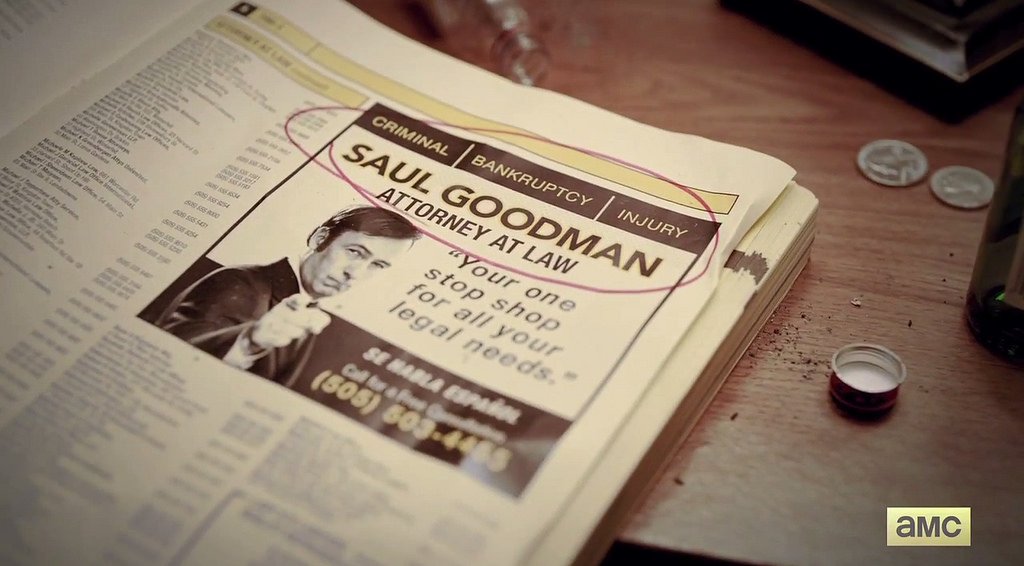

Its pace and tone, too, differ from the original, with many viewers finding the show’s relatively slow pace off-putting. That, however, is the point. The ‘Jimmy McGill’ we are introduced to is not yet ‘Saul Goodman’ and, crucially, his metamorphosis must feel organic.

Better Call Saul is not simply a series of skittish side adventures (although comedy is an essential component of the show). We find Jimmy Not-Yet-Saul to be a complex character, morally ambiguous, but hardworking and willing to go to great, and sometimes unethical, lengths for those he cares about.

He is, for want of better terminology, pond-life, struggling to stay afloat. While certainly never being saccharine, Better Call Saul is at times moving, because the viewer is made to empathise deeply not only with Jimmy (to the extent that ‘Saul Goodman’ seems to be something of a façade) but with those around him as well.

Walter White’s maxim still applies: this show is “the study of change.” The overarching theme of both shows is the central character’s metamorphoses. But the show’s success at finding a new angle on the same core theme, whilst still being a worthy complement to the original series, more than justifies Better Call Saul’s existence.