The bell chimed for 2 o’clock on Thursday the 21st of March and the doors closed for the Oxford Literary Festival’s most controversial talk: ‘Sharron Davies, Unfair Play: The Battle for Women’s Sport.’ I stood on the step of the main entrance wearing my ‘festival steward’ lanyard, and contemplating the politics of being a volunteer at what felt like a history-making event. There had been no protest, no commotion, and the courtyard around the Sheldonian was relatively calm, but the moment felt monumental. The memory of philosopher Kathleen Stock’s infamous 2023 visit to the union weighed heavy on my mind. The event was a watershed moment for what has become a particularly intense transgender debate here in Oxford, famously spawning public tensions between faculty and student activists that foregrounded important critical questions about the limits of free speech and the power of student protests.

The Davies talk was a weird episode in the current history of the transgender debate in Oxford. As festival volunteers, we had the option of attending the event for free whilst tickets ranged from eight pounds to twenty, but the decision to hang around felt loaded. The Easter vacation had essentially flattened the student response to the talk, in stark contrast to Stock’s term-time visit. The ticketed entry seemed to further limit attendance, and although student tickets could be purchased at a discount, the issue of handing money over to figures like Sharron Davies poses its own problems. The student reaction was certainly voiced in a condemning Instagram post by the LGBTQ+ campaign of the Oxford Student Union and an article by Éilis Mathur for Cherwell, but in the quiet courtyard of the Sheldonian, there was not a protester to be seen. And unlike the other events, no members of the press showed up at the door I was ticketing; indeed, reception of the event, both local and national, has been incredibly quiet. It was the subdued atmosphere of the theatre which tipped me towards attending Davies’ talk. As it seemed the lofty Sheldonian could become a literal echo chamber, it felt important that I take advantage of my free seat and expose the conversation to the wider student community.

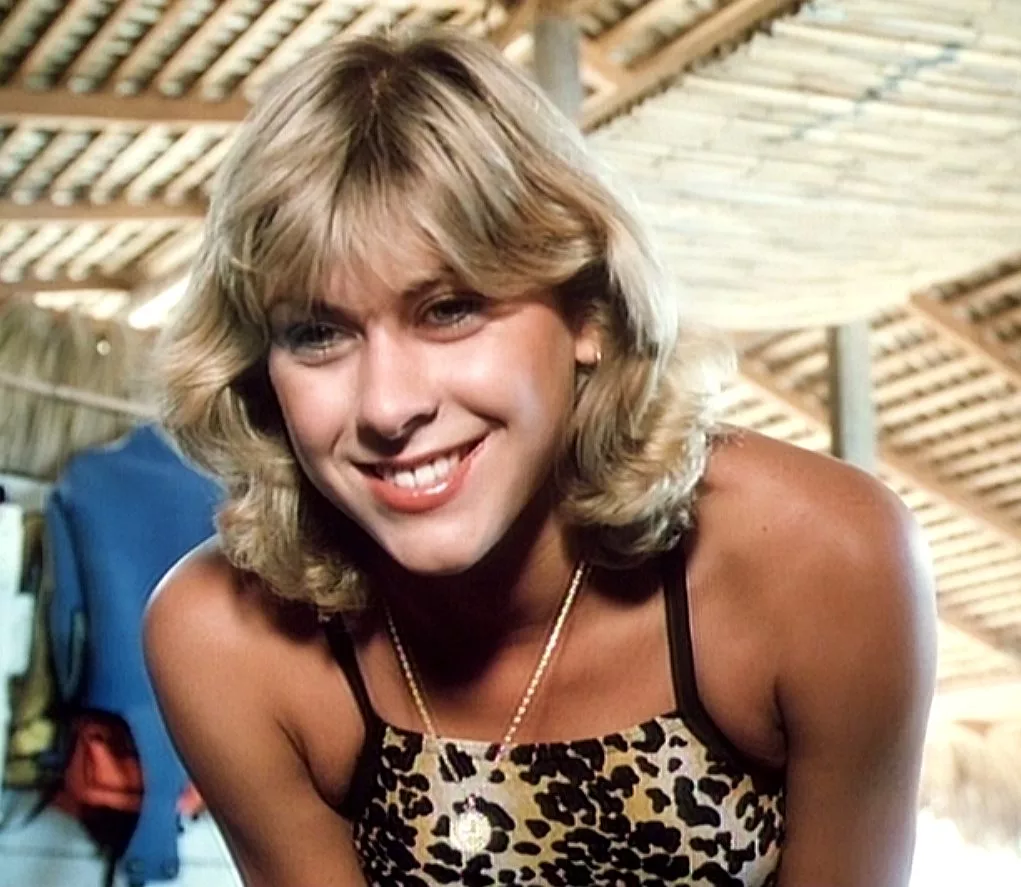

Sharron Davies is a former competitive swimmer, who competed for England in three Olympic games. Since retiring from the sport, she has worked as a sports commentator for BBC and was an advocate for London’s bid to host the 2012 Olympics. She is a supporter of the Conservative party, endorsing Kemi Badenoch in the 2022 leadership election. Since 2019, she has become well-known as a vocal supporter of the separation of cis- and transgender athletic spaces, a concern which rests on her experiences swimming in the 1980s at the height of the infamous East German doping scandal. It’s a powerful opener. Davies had been frontline in the affair, racing against no fewer than three East German swimmers who were participants in a program which saw female athletes deceived or bullied into taking ‘vitamin pills’ containing anabolic steroids. Davies outraced two and came in second place behind the final East German swimmer, Petra Schneider. The Oxford literary festival website refers to her as the athlete who “infamously missed out on an Olympic gold.”

These experiences underline her conviction that Olympic Sport committees, plagued by systemic misogyny, have continually allowed the mistreatment of women to go unnoticed and unchallenged. Part of this misogyny, she argues, is the willingness to turn a blind eye to the ‘unfair’ participation of transwomen in women’s sports. As with the doping scandal, Davies suggests that Olympic boards have not been willing to properly invigilate women’s sports because they do not value women’s victories as much as those of men. This undervaluing of women’s sport has, the argument goes, led to committee boards ‘taking the easy route’ by denying that there is a difference in performance capabilities between cisgender athletes and transgender athletes which she does not find to be a workable solution.

Convincingly, Davies exposes the complications inherent to the debate, identifying that the effects of ‘male’ puberty, which are not reversed by HRT – such as increasing bone density and muscular development, and a narrower angle between the hips and knees – can provide an unfair competitive advantage, particularly in fighting sports. It certainly seems important then, to differentiate sports categories in more than simple ‘male’ and ‘female’ categories. Whilst many of us would agree that these categories do not capture such complexities, Davies’ proposed ‘solution’, which involves separating transgender athletes from their cisgender counterparts, fails to convince.

There is a twofold problem with Davies’ case for a segregated athletic space. As with many of the classic arguments associated with the TERF (Trans-Exclusionary Radical Feminist) position, there is a total lack of intersectional awareness in the argument. The existence of systemic misogyny within professional sport is indubitable. But Davies, despite aiming to appear sympathetic to the transgender experience, mistakenly suggests transgender and cisgender athletes compete for the same space, which they cannot both occupy. As she terms it, “Women already have a small piece of the pie, and it is becoming smaller,” a sentiment epitomised in her suggestion that Lia Thomas was a ‘mediocre’ swimmer when she had competed in the ‘male’ category, and therefore should not have enjoyed such success as she did competing as a woman. This time round, Davies chooses moderate language, but an article from The Times in June 2023 quotes her referring to trans athletes as “mediocre males self-identifying their way out of biological reality to a new status in sport.” It’s not a good look. While Davies claims to put the crux of the issue on Olympic committee boards, not individual athletes, the idea that transgender women are being allowed to ‘take pieces’ of the womanhood ‘pie’ inevitably and unfairly pits athletes against each other.

Moreover, Davies gestures towards biological definitions of womanhood. For example, she talks with sympathy, though not without an agenda, about the tragic effects of the doping program, making specific references to Schneider’s struggles with fertility. Another moment sees interviewer Andrew Billen pose a question about the perceived dangers of allowing transgender women to to share changing rooms with their cisgender teammates, focusing on the presence of male genitalia in ‘female’ spaces and the possibility that there is an inherent power dynamic tipped in the favour of male-to-female transgender athletes. Davies contributed to this narrative by drawing attention to the very real financial vulnerability of often single-sponsor female athletes to the problematic effect of suggesting that they are forced to accept the unwanted or (it is implied) traumatising presence of ‘men’ in women’s spaces. The focus on making safe spaces for women would no doubt be more fruitfully directed at handling the abundant cases of sexual misconduct by cisgender coaches, a much more common and persistent fear for young female athletes.

In one especially ‘on the nose’ moment, interviewer Andrew Billen asks Sharron Davies if she sees herself as a TERF (Trans Exclusionary Radical Feminist) and she responds by saying that she identifies as a woman, and a mother. It is perhaps no coincidence that one of the only places that the Literary Festival event shows up on the internet (besides the festival website) is in a forum post on mums.net. The appeal to motherhood as an identifier of cisgender womanhood clearly strikes a chord with Davies’ supporters.

A question from an intersex member of the audience provides the first and only real challenge to Davies’ views. The questioner suggests that the language around intersex people in Davies’ book is awkward and dehumanising, suggesting that Davies had implied that intersex was not an identity but a biological abnormality, and asks if Davies has any advice for intersex individuals who feel excluded from professional sport. After some disagreement on the appropriate way to refer to the intersex community (with Davies suggesting ‘Diverse Sex Characteristics, is more representative, whilst the audience member defends their choice of label) Davies then questions why intersex people would feel excluded from professional sport, whether this feeling of exclusion is justified. Her tone – defensive rather than encouraging – and her insistence on the lack of social barriers into a professional sports career is bizarre. I find myself wondering why Davies doesn’t simply apologise for a poor choice of language and exercise some of her inspirational-speaker-meets-life-coach muscle and deliver some token inspiration about chasing dreams and overcoming hardships. Instead, she chooses to argue about the language of a community she does not represent, adopting a tone-deaf approach to an invitation for words of encouragement. Although the end of the talk sees the two shake hands relatively cordially, it is not a flattering or compassionate moment.

Despite all of this, Davies’ talk does leave room for optimism. Although Davies was only directly challenged by one advocate for the LGBTQ+ community, a sense pervaded the event that she is conscious of LGBTQ+ and student sensibilities on this sensitive issue. For example, Davies’ use of gender reaffirming terminology, her tempering of some of her former sentiments about Lia Thomas, and diligence in professing her sympathies for the struggles of the transgender community demonstrate the kind of awareness brought about through protest and activism, such as the interruption of Kathleen Stock’s appearance at the Oxford Union and the SU’s LGBTQ+ campaign callout post. The result was that the voice of student LGBTQ+ activists was ‘present’ in the room, even at an event that saw limited attendance by Oxford students because of the vacation. One comment in the mums.net forum read,“Oxford, eh? I hope that a horde of screeching blue hairs doesn’t turn up to ruin the event.” Perhaps we should see this ‘blue-haired Oxford effect’ as a small win for activism.

What should we make of these observations? It is difficult to be an activist. It is often the case that the activist space feels dark and defeatist. Hopefully, the indications that Davies is more conscious and attuned to the sensibilities of an LGBTQ+ audience suggest that activism has worked to the effect of forcing public figures to be held accountable for their language. The movement should take some pride in that accomplishment.

However, the subdued atmosphere at the Sheldonian and the framing of Davies’ potentially trans-exclusionary arguments reflects an uncomfortable reality. There is talk everywhere of a ‘tide turning’ towards the Conservative position on the sports issue. Sharron Davies states her conviction that she would not have been platformed at the Oxford Literary Festival even just two years before. Sports committees are increasingly banning transgender athletes from competing with their cisgender counterparts, without an effective solution having been reached.

I reflect on the quiet and uncontested filter of people into the Sheldonian, the sparse ticket queues. The event is not even close to selling out. The initial storm of debate about the inclusion of transgender athletes seems to be fading away. I hope that we might capitalise on the increasingly omnipresent concern for accountability to enter a compassionate debate on the right way forward, rather than leaving the decision to be quietly made uncontested in the boardroom of the Olympic committee. It is essential to prevent such significant cultural moments from sliding quietly under the radar. But inevitably we are forced to accept the classic, if hard-to-swallow reality that there is still more work to be done.