In the years since Cecil Day-Lewis’ death in 1972, the poet’s work has not received much critical attention. Instead, his name is often forgotten due to the more prolific works of W.H. Auden, with Day-Lewis’ work seen as a mere fragment of what was produced by poets during the ‘Auden generation’.

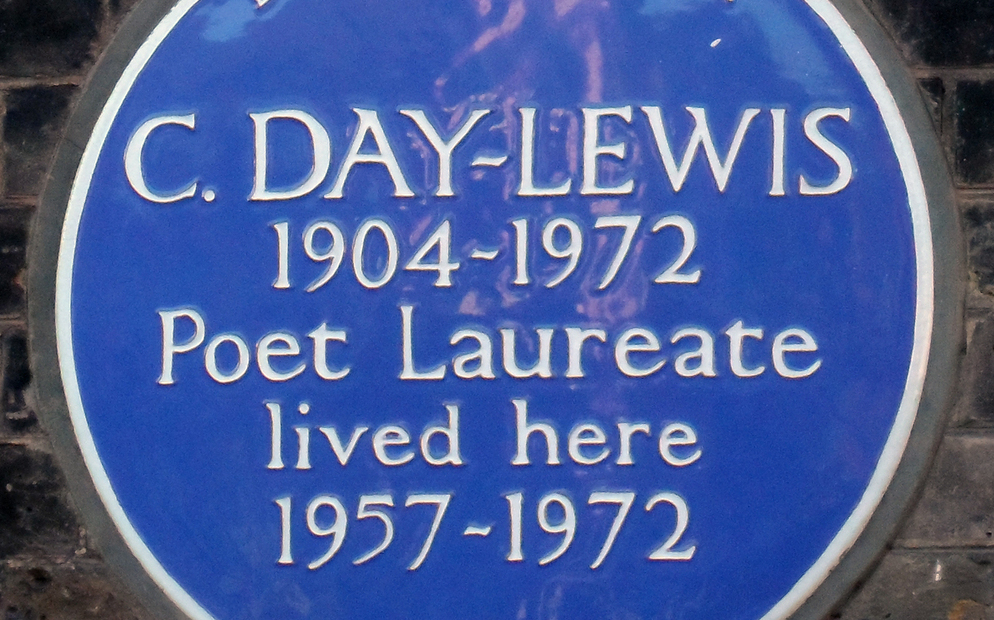

Contemporaries at Oxford, Day-Lewis and Auden went on to become joint editors of Oxford Poetry in 1927, but Auden was the dominant figure of the pair, despite the fact that Day-Lewis himself went on to become Poet Laureate from 1968 until his death in 1972. Perhaps most notably, he even had a stint writing for Cherwell.

In spite of this, Day-Lewis was not confident in his own academic ability. During his time at Wadham College, he found his focus on academic work wavering, saying later, with “A fourth in Greats—and it is a mystery to me why the examiners did not fail me altogether.”

Yet, Day-Lewis may have over-exaggerated these difficulties to mark a contrast with his eventual return to Oxford in 1951, when he was elected as Professor of Poetry. Nonetheless, it was not until he met Auden in his last year at Oxford that he could fulfil the romantic identity he had created for himself as a poet.

Alongside figures such as Louis MacNeice and Stephen Spender, Day-Lewis was intrigued by the more intelligent and energetic Auden—who led the ‘Auden Group’, known for their left-wing political views.

Day-Lewis was a member of the Communist Party from 1935 to 1938, and some of his poetry was marked by didacticism and a preoccupation with social themes. Even some of his most romantic poems are inextricable from his political views.

One of these poems is ‘Come, live with me and be my love’, which follows the speaker telling his beloved that he lacks material wealth, and even the barest essentials, evoking periods of economic depression in the twentieth century.

One cannot help but notice how this poem aligns with Day-Lewis’ personal life. After all, it may speak to his first wife Mary King—who at first found it difficult to love him.

Oxford’s influence over Day-Lewis seems clear: it was not the academic experience he benefited from. Rather, it was the friends he met that secured him a series of posts as a schoolmaster. He continued publishing collections of poems, novels and essays before, during and after the Second World War.

While students across the country may not be familiar with Day-Lewis, his link with Oxford is everlasting. As recently as 2012, papers from his archive were donated to the Bodleian Libraries by his actor son Daniel, and daughter Tamasin. Perhaps Day-Lewis needed Oxford, not for its academic excellence, but to be inspired by his poetic peers.