I Think in Pictures is a veritable treasure chest of hidden colour and symbolism, displaying an oeuvre that defied East-Germany’s standards of Socialist Realism whilst also offering up a commentary on the modern man for those wishing to read it. The presentation of A. R. Penck’s work is deliberately codified, down to the artist’s true name, in a way that defies our regular expectations of an exhibition.

Prefacing the exhibition is a short biography of the artist, but beyond that the set-up is very minimalistic. The room’s white walls allow the powerful colours of Penck’s paintings to pop. It was a small yet very organised special set-up which I found was interestingly claustrophobic yet practical. The entrapped nature of this exhibition space is significantly seen in the way that his largest piece, Edinburgh (Northern Darkness III), 1987, stretches fully from floor to ceiling like a great wall. A brief explanation of the piece describes it as a history painting commenting of Gorbachev’s reform programmes and conflict in Northern Ireland, but also suggests it to be a work more generally about control structures in social systems. The gallery contends to this idea: a deliberately placed bench persuades you to sit and consider the piece; the wall and ceiling boxing in the piece create a sense of constriction; overall the viewer finds themselves not only looking at the paintings but also possibly sympathising with Penck’s own feelings of restriction.

A lack of adjoining commentary pushes you to create your own readings of the works in a symbolically non-restricted way too. By being allowed to reach your own conclusions about Penck’s work, you are thrown in the deep end without much context – I do think, however, that this was a very smart and poetic decision on behalf of the Museum.

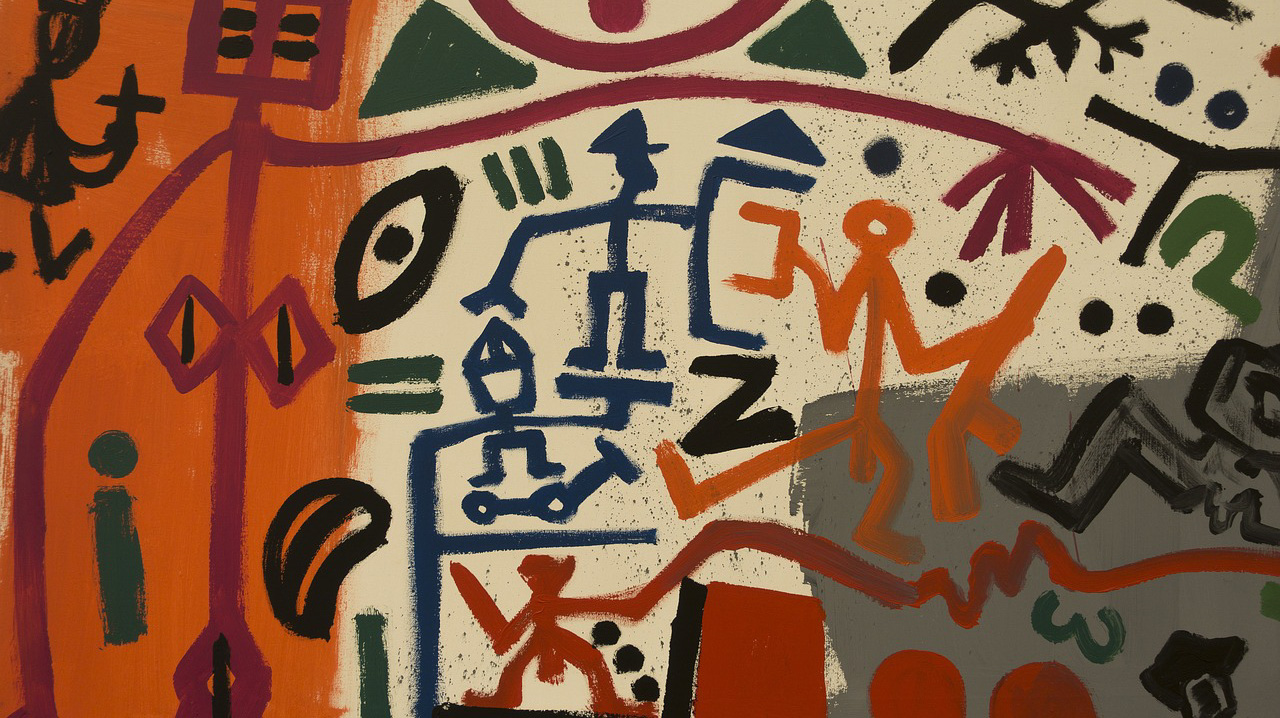

I Think in Pictures plays with the notion of art as a conveyor of many messages – even without the presence of the written word. One might find themselves drawn to the mysticism on the Standart figure of his Nine Works: Untitled (1982) or N-Komplex (1976) for instance as a symbol of fear and surrender as instigated by conflict. We as the viewer face him, but it is unsure if we are in the shoes of the assailant or are bystanders of an act of suppression. The symbol is a contemporary response to the spirit of fear of the Nazi regime and yet also could make one think of examples modern political suppression as well.

Penck’s alias (his true name being Ralf Winkler) gave his identity a sense of mysticism with which he used to shroud himself and give him the freedom to create under less scrutiny. In a same way, we are not given much of an intellectual framework to go from, and therefore are at liberty to interpret his work as we like. His work is unlike any other Symbolist work I have seen before. He creates his own universal artistic language that addresses the viewer that was rejected during his time because it was “unacademic”. Supposedly, the exhibition defies modern art historical categorization, with his works treading the lines of Expressionism, Primitivism and in some forms Surrealism. His sculptures remind me of Giacometti’s elongated, stick-like forms and made me consider a more Existentialist quality to his work.

Ultimately, the exhibition pulls you in with some contextual starting point, but ultimately leaves you to do your own ‘research.’ We are given a dichotomy of the mystery that is Penck-the-person and an oeuvre which aims to create a language that can be understood. It was a gem of an exhibition to visit and is one that I highly recommend people should visit. Take the time to sit before Edinburgh, to consider the oeuvre, and think in pictures as Penck once did.