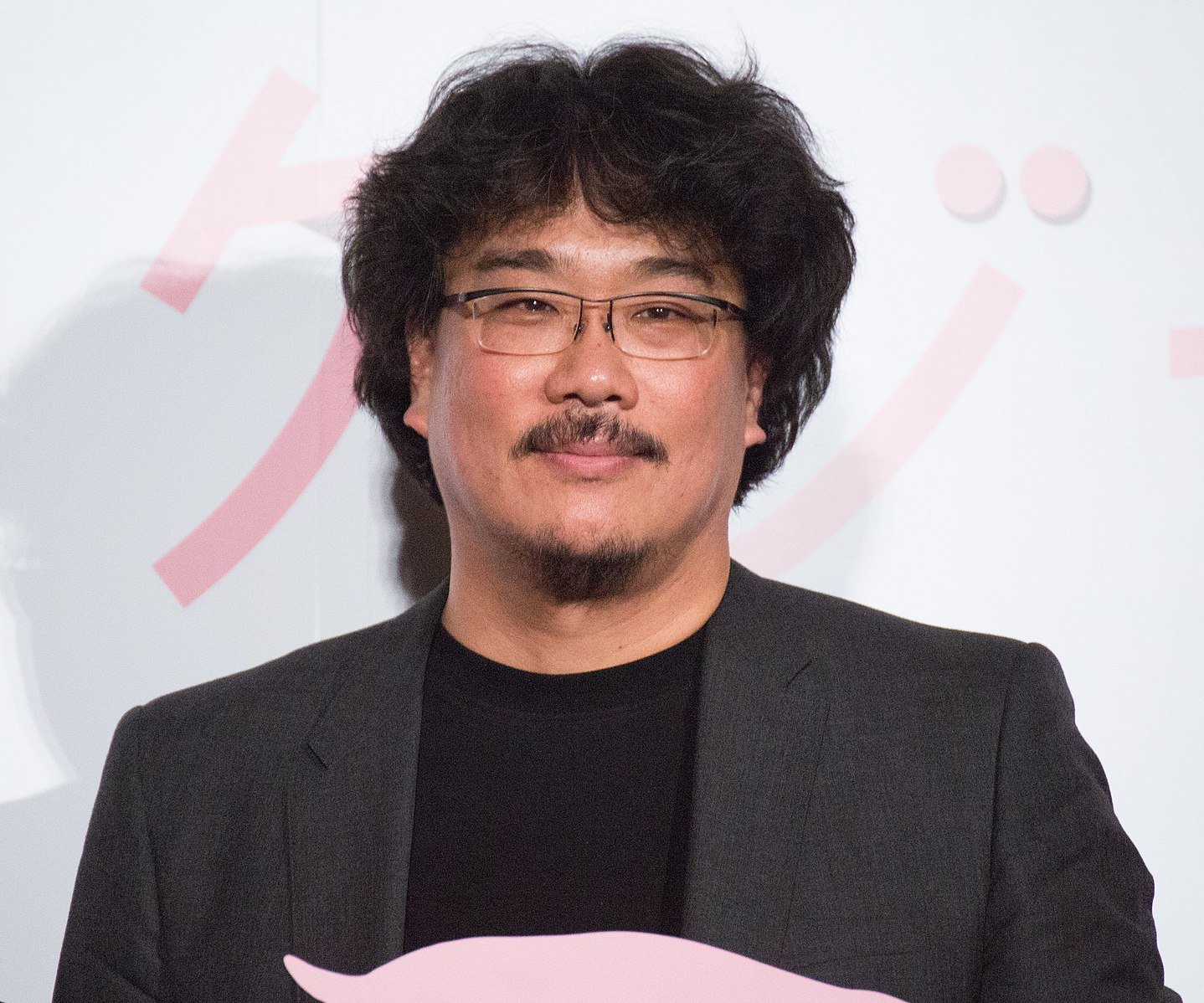

Perhaps the last, if not only good thing to happen this year was the ascension of Korean director Bong Joon-Ho from cult film legend to global cultural icon. As a film fan, it’s always satisfying to see one of world cinema’s leading auteurs make a break into the mainstream, especially when it’s for a work as urgent and accomplished as last year’s Parasite. Of course, a meteoric rise to fame like this yields countless new fans desperate to find out what else the director has to offer, and to answer that very question Curzon Artificial Eye had released into cinemas nationwide – before the second lockdown’s untimely interruption – Bong’s breakout (and, I’d argue, best) film: 2003’s Memories of Murder.

On a level of pure formal control, Bong is undoubtedly one of the true masters of his generation – his gift for painterly compositions and narratively forceful staging is akin to that of Kurosawa, whilst his brutally efficient cutting, intricate plotting and sense for cinematic rhythm calls to mind Hitchcock – but Bong consistently backs up this technical precision with an attention to thematic and emotional detail that, combined with his now infamously anarchic approach to genre convention, renders him a singular force in the landscape of modern cinema.

The director’s most commercially successful releases tend to be those where he’s at his boldest and most bluntly allegorical, from The Host’s monster-as-product-of-American-Neo-Imperialism to Snowpiercer’s train-as-capitalist-class-structure and Parasite’s more refined, vertical reinvention of the same central metaphor. But Bong has also proven himself capable of comparatively more grounded, low-key works (‘comparatively’ being the key word here – this is still the man who made Chris Evans slip on a fish), such as 2009’s Mother, a taut, oedipally charged thriller about a mother trying to clear her son’s name after he’s accused of murder and, of course, Memories of Murder.

Memories gives a loosely fictionalised account of the investigation into the Hwaseong serial murders, a series of rapes and killings that occurred between 1986 and 1991 – particularly notable for two reasons, one being that they were the first serial killings South Korea had known, the other being that, until a year ago, they had never been solved, with the mystery remaining in the public consciousness for decades.

The film concerns itself mainly with Park Doo-Man (played with typical bravura by regular Bong collaborator Song Kang-Ho), a local detective claiming to have ‘shaman’s eyes’ who stumbles upon the first of the murdered girls and finds himself, alongside his partner, woefully out of his depth, as it becomes apparent that the tried and tested small-town cop method of ‘catching criminals with your feet’, forging evidence, and beating confessions out of any suspect you can find doesn’t quite hold up to scrutiny when dealing with a meticulous and methodical serial killer. Enter Seo Tae-Yoon (played by Kim Hyang-Sung), a big-city cop sent to help from Seoul whose methods differ drastically from Park’s, with his derision of the former’s reliance on folk wisdom, his assertion that ‘documents never lie’ and his nagging insistence on paying close attention to the evidence at hand.

In typical Bong fashion, this ideological conflict is exploited for maximum comic effect – Detective Park tries everything from going to public baths to look at men’s pubic hair to consulting a mystic for help with the case – but Bong is the master of the tonal tightrope walk, and accordingly, this humour is rooted in a tangible sense of frustration and despair that eventually comes to consume the whole film as its main characters sink further and further into obsessive desperation, making sure that the horrific nature of the violence at the heart of its story never leaves our minds.

Adding to this is the attention Bong gives to the political situation at the periphery of the narrative – the South Korean military dictatorship of the 1980s. Though the violence of the police in the film is initially presented as slapstick, it’s indicative of the widespread, state-sanctioned violence that plagued the country in the aftermath of 1980’s Gwangju massacre.

In one short sequence relatively early on, we bear witness to our detectives in one of the many brutal confrontations that took place between police and student protesters across the nation throughout this period. Later, the detectives find themselves unable to call upon a garrison to help catch the killer due to them being busy suppressing yet another demonstration. And in one of the film’s most upsetting moments, we watch as the killer takes one of his victims in the midst of a routine air raid drill. Here Bong’s camera remains cold and still, firmly focusing on the girl’s terrified face as the sirens in the background make his point to us clear: this could have been prevented. For Bong, the blood of these women is as much on the hands of the militaristic government as it is those of the elusive serial killer.

Memories starts as ostensibly a subversive and irreverent story about detectives solving a murder case. But it reveals itself to be instead an exploration into the irrevocable psychological agony of desperation and defeat, an indictment of a fascistic regime that, through its own authoritarianism and institutional incompetence, allowed this murderer to commit his crimes, and perhaps above all, a sort of exorcising of a collective trauma still present in the Korean national psyche at the time of its release. Bong bookends his film with images of children, a deeply resonant, if not especially subtle, symbol of innocence – an innocence that is, in a way, shared by Detective Park at the film’s start, and one that he no longer knows by its end.

Now the film is being presented in a new 4K restoration, allowing Bong and cinematographer Kim Hyung-Ku’s rich, carefully crafted imagery to be seen in the optimal digital format, as clear and crisp as it’s ever been. Its look is a persistently tactile one, and this new restoration only deepens its sense of visual texture, from the golden wheat fields of its opening, to its grim and grimy police station basements and the rain-drenched train tracks of its sombre climax. Combined with the elegiac piano score from Japanese composer Taro Iwashiro, an atmosphere of melancholy is established from the first shot, one that’s sustained and even expanded upon right up until its spine-chilling final frame. Memories of Murder is one of the great masterpieces of not just Korean cinema, but 21st century cinema as a whole.

Image via Wikimedia Commons / Dick Thomas Johnson