Throughout history, art has left an indelible cultural impact on humanity’s collective understanding of war. Picasso’s ‘Guernica’ is perhaps the most famous manifestation of this; but the richer historical tradition is certainly written, with a heritage as far back as Homer’s Iliad and its depiction of the Trojan War. As the outbreak of conflicts in Ukraine and Gaza over the past two years have made the public more cognizant of modern warfare – and while other conflicts continue to elude that public attention, such as humanitarian tragedies in Myanmar, Sudan and the Sahel it seems the right time to reflect on the power of words to poignantly portray the horrors of war for a civilian audience.

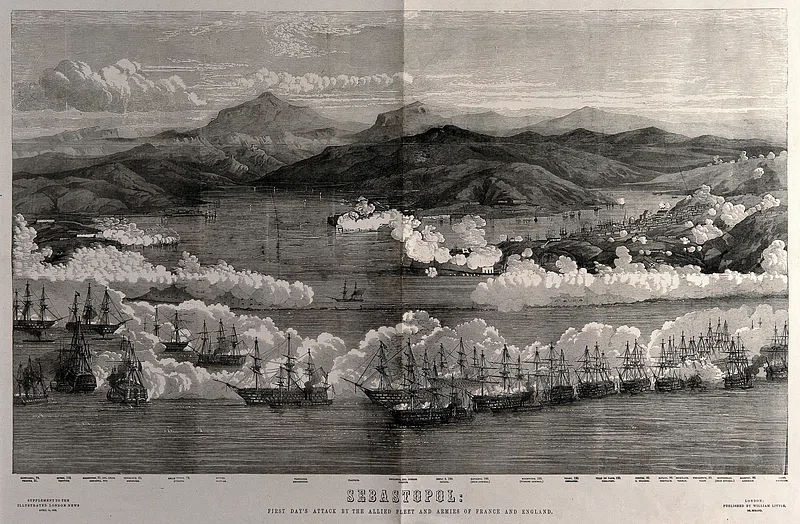

Mark Rawlinson argues that modern war literature is “incontestably a literature of disillusionment”, something he attributes to Tolstoy’s War and Peace (1869). This “disillusionment” that comes through in the war narratives was true of Tolstoy’s own military past, fighting in the Crimean War during the Siege of Sevastopol (1854-55); but crucially, it also sets a precedent for modern war writing, which does away with the romantic, top-down narratives of battles that had dominated previously. Despite the grandeur of War and Peace as a ‘historical novel’ (a label its author would have disputed), Tolstoy grounds its scenes in the horrible realities of war and with themes of ignorance and cowardice grounded in a realism akin to Stendhal’s depiction of the Battle of Waterloo in The Charterhouse of Parma (1839). As a historian, Tolstoy repudiated the two most prominent theories of history that of ‘great men’, and that of Hegelian determinism to demonstrate the helplessness of soldiers against the “antagonistic relation” of their countries. It is through this that Tolstoy gives a bleak picture of war, rooted in its grim realities of unglamorous death and wanton destruction: a picture that had a lasting impact on war literature; specifically, its power to resonate with readers’ emotions and senses of morality.

Modernist literature of the early 20th century, over which the First World War cast an unmistakable shadow, also reflected a ‘morality’ which was rooted in the ‘reality’ of war. Modernist culture itself represented the “cumulative trauma” (Adam Phillips) of that war, which like War and Peace sought to reject any notions of heroism or romance in the Great War; this was made clear with the powerful anti-war message of Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front (1929). The war literature of the early 20th century, while imbued with a distinctly modernist sense of nihilism, also harked back to Tolstoy’s insistence on the futility of war: Andrei’s “jeremiad” (Rawlinson) on page 775 is not dissimilar from some of the poetry of Siegfried Sassoon. Modernism in literature involved the desire to overturn traditional modes of representation in light of war’s horrors, placing the soldier’s experience at the fore to emphasise the true depravity of which mankind is capable. While modern media exposes the terrible humanitarian cost of wars to the public through ever-more-accurate photos and videos. In the days before technology there was something uniquely powerful about the written word in questioning the value, cost and morality of warfare. This literature was a world away from the antediluvian depictions of warfare as glorious and heroic; patriotic accounts by Robert Keable and Ernest Raymond have not made their mark on posterity.

Indeed, in contrast to the hubristic accounts of victory presented by Renaissance humanists like Leonardo Bruni, modern war literature tends not to see victory as anything more than Pyrrhic; William Manchester’s Goodbye, Darkness: A Memoir of the Pacific War (1979), for instance, presents the reader with horrific accounts of death and human suffering. Even more recent was Sam Hamill’s 2003 Poets Against the War project, which reminds us of the continuing power of literature to act as a cultural bulwark of peace. Yet while the writings of Tolstoy, Sassoon and Martin Luther King present necessarily bleak anti-war messages, we must not lose sight of the power of war literature to bring hope during the bleakness of war itself. As Berthold Brecht pointed out in 1939, there would be singing during the dark times ahead about the dark times, but singing nonetheless.