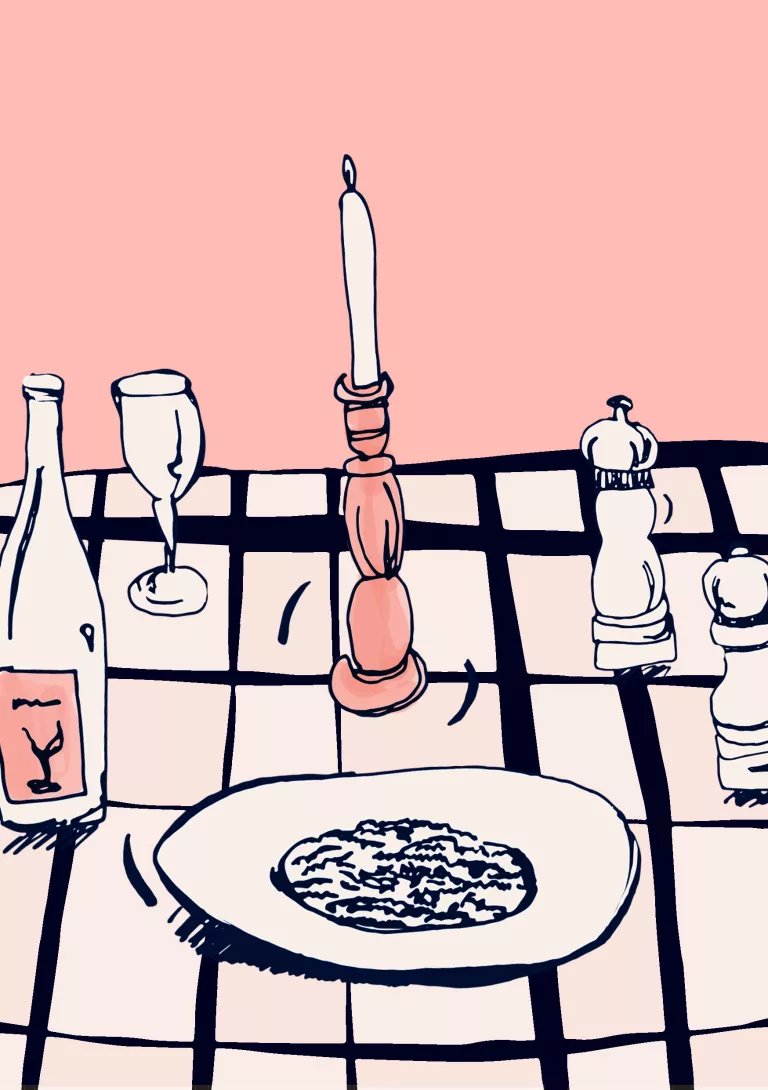

Under Oxford’s dreaming spires and overlooking Magpie Lane’s centuries-old cobbles is a simple modern kitchen. I like to think of it as my friends’ little corner of the world. Here, nine or so teenagers gather for homemade meals twice a week, crowding around induction hobs and squabbling over how an onion ought to be chopped. We claim a space at the heart of Western scholarship and fill it with aromas of multi-ethnic cuisines that reflect our diversity.

I remember, surrounded by this warm messiness, the many times I’ve spoken the language of cooking.

– – –

When a flock of chattering Chinese-American aunties congregate for the terrifyingly efficient task of folding dumplings, you can always tell which dumplings are produced by whom. Some arch like the spine of a mountain, sealed by intricate folds the shape of a lotus flower, others lie flat like a tame leaf, smooth-edged and round-bellied.

My mother’s dumplings sit primly with curves like the crescent moon – a shape she learned from my grandma, a petite woman with missing teeth and a lyrical Shandong accent. My grandma learned it from her own mother, a beauty with 4-inch-long feet crushed by societal expectations of the last foot-binding generation. Inherited from this line of Northern Chinese women, the crescent-moon dumpling is now proudly mine.

Dishes, like stories, pass down through generations. In my California Bay Area community, most Chinese families know some version of dumpling-making, much like the commonalities found in stories of shared culture and history. We fold these stories into existence through shared words – ingredients like fluffy flour and minced meat – and common grammar – the skilled kneading and flattening of dough under soft palms and hard rolling pins.

Cooking, then, is a language we speak.

We gather for potlucks on Chinese New Years and Moon Festivals, our multicultural cuisines and bilingual murmurs building a new home an ocean away from our homeland. If I translate our language of cooking, we’d be saying: 四海为家. This is family.

– – –

I learned the language of cooking when living in Morocco on a year-long US government program to study Arabic. With each personal connection and unplanned adventure, I fell deeper and deeper in love with the wide world out there, wonderstruck. But at the same time, the awareness that I was the only Chinese person around grew sharper, a wound irritated by the constant harassment that followed me down the streets.

“Ching chong Jackie Chan.”

“Korea?”

“So you’re not pure American.”

Since moving to the US aged eleven, I’d been living in an Asian-majority community that taught me to believe America is a country of immigrants, even if some people refuse to accept this fact and its beauty. Home is where I order tacos in Spanish, organise Indian catering for debate club, and make spring rolls with my half-Vietnamese family-friends – I call them my cousins when I don’t bother explaining that we are family in every way but blood. Yet, the doubts and confusion of Morocco made me wonder, guiltily, if I was American enough.

My palette soon began craving Chinese food but there wasn’t a single Chinese restaurant in my city. So I made my first Chinese dish for my host family: a simple dish of tomato and fried egg noodles, cooked with trepidation that they might dislike the strange flavours. In the language of cooking I was probing, uncertainly, “my home tastes like this – is it acceptable?”

Their response was lukewarm.

– – –

The Western holiday season marked peak homesickness for my American friends in Morocco, many of whom had never spent the holidays away from family in a country that didn’t celebrate it. On Christmas Day, we gathered for a potluck party.

I brought hot chocolate and most of my friends brought sweets. However, George went all out and made fifty Vietnamese spring rolls with exquisite peanut sauce. I imagined his meticulous preparation process: a white guy from Virginia softening sheets of rice paper in warm water and tucking chopped salads inside.

My Jewish friend Jacob remarked that it was his first Christmas without eating Chinese food. He explained how, in New York City where he’s from, Jewish families have a centuries-long tradition to get Chinese food on Christmas Eve because no other restaurants were open. He remembered waiting with friends in the biting cold to get their takeout. I pictured the scene: Christmas lights, Hanukkah candles, and red lanterns all decorating the same street where queues of Jewish residents wrap around the corner like an embrace. I pictured America.

If I’d known about this tradition, I told him, I’d have cooked for him that Christmas. In the language of cooking we’d have a conversation between two minorities that historically didn’t fit in, but found their place nonetheless.

– – –

Slowly I began meeting the few Chinese expats living in Rabat and some Moroccan university students studying Chinese. Together we dunked thinly sliced meat in bubbling hot pots and folded sticky rice balls around sweet stuffings for the Lantern Festival. I thought I could teach my Moroccan friends to make dumplings.

To a medley group, I demonstrated rolling and folding techniques. They quickly caught on after a few oddly-shaped experiments. Imane and Sara, especially nimble-fingered, filled up a large tray at impressive speeds. Watching the dumplings tumble in a pot of foamy hot water, I mused that there was something unusual about all this.

Then it clicked: All the dumplings looked the same. They all sat primly with curves of the crescent moon – like mine, my mother’s, and my grandma’s.

I thought of how, so far away from my grandma in China and my mother in America, I passed on our crescent-moon dumplings. I told our stories, encoded in the language of cooking. I said: “thank you for celebrating my culture.”

– – –

By the time Ramadan rolled around in late March, I was speaking in Moroccan dialect and functioning in society undaunted. I decided to fast. For a month, I went without food or water from 4am to 7pm before feasting on iftar meals, the hunger and thirst bonding me closer to my local community.

I pondered what to cook for a potluck iftar at school and settled on orange chicken, a fusion cuisine invented for Americans with inspiration from Chinese food. Orange chicken represents the unique branch of food created by centuries of Chinese immigrants in America – inauthentic to the original but glazed with a unique social and historical value.

Chinese cooking never uses precise recipes but rather asks you to judge what is “just right,” relying upon instincts developed over a lifetime. My orange chicken, too, was a whimsically instinctive creation. I fried battered chicken and caramelised them in bubbling orange sauce, with spring onion and sesame tossed into the sizzling pan. The resulting sweet and tangy dish was devoured with fervour by Moroccans and Americans alike.

I overheard one of my American friends explaining to a Moroccan that this chicken is not merely Chinese, nor merely American, but a fusion of both in its essence.

Like me, I thought.

While I had been experimenting with cooking since childhood, my early attempts were like mere babbling – flavours without a profound meaning. But in Morocco I found my culinary fluency, the composition of prose and poetry in a blend of recipe and creative flares. I was saying: “I’m Chinese-American.”

During my last week in Morocco, I decided to cook tomato and fried egg noodles again. I kneaded fluffy dough and cut strips of noodles by hand. I knew my way around the kitchen.

What was once a question had now morphed into a declaration: “My home tastes like this.”

My host mom took a bite. “Bnin bizaf!” she said. Very delicious.

– – –

I returned to California with new vocabulary in my language, chickpeas and turmeric and other ingredients I’d never used before. With these, I made harira soup and chicken tagine for friends and family, giggling at their struggles to eat with fingers instead of forks or chopsticks. Through cooking I was saying, “Morocco is my home too, and I miss it.”

– – –

Another year, another home. From different colleges around Oxford, my friends regularly flock to our little kitchen, the spatial heart of our group. Liyanah, of Sri Lankan heritage, made us curries with rich and spicy flavours just like her mother’s. Will, Christmas-obsessed but denies it, made reindeer fudge and brought us a cupcake-decorating kit – resulting in some artistic masterpieces and some less-than-mature jokes. I cooked everything from simple ramen to more elaborate dishes like orange chicken, Mexican rice, and Moroccan tagine.

Not only do the dishes express meaning, so does the context of sharing. The early morning noodles during freshers’ week were an introduction, a “not sure who you are yet but hey” to Lucas and Jake, two then-strangers who have now become my close friends. The pasta on a random Tuesday when our dining hall cancelled dinner on short notice was a message of care, a “don’t worry, I’ve got you.” The taste-test hash browns I offered to neighbours, knocking door to door, were also my checking-in, an “it’s been intense, how are you doing?”

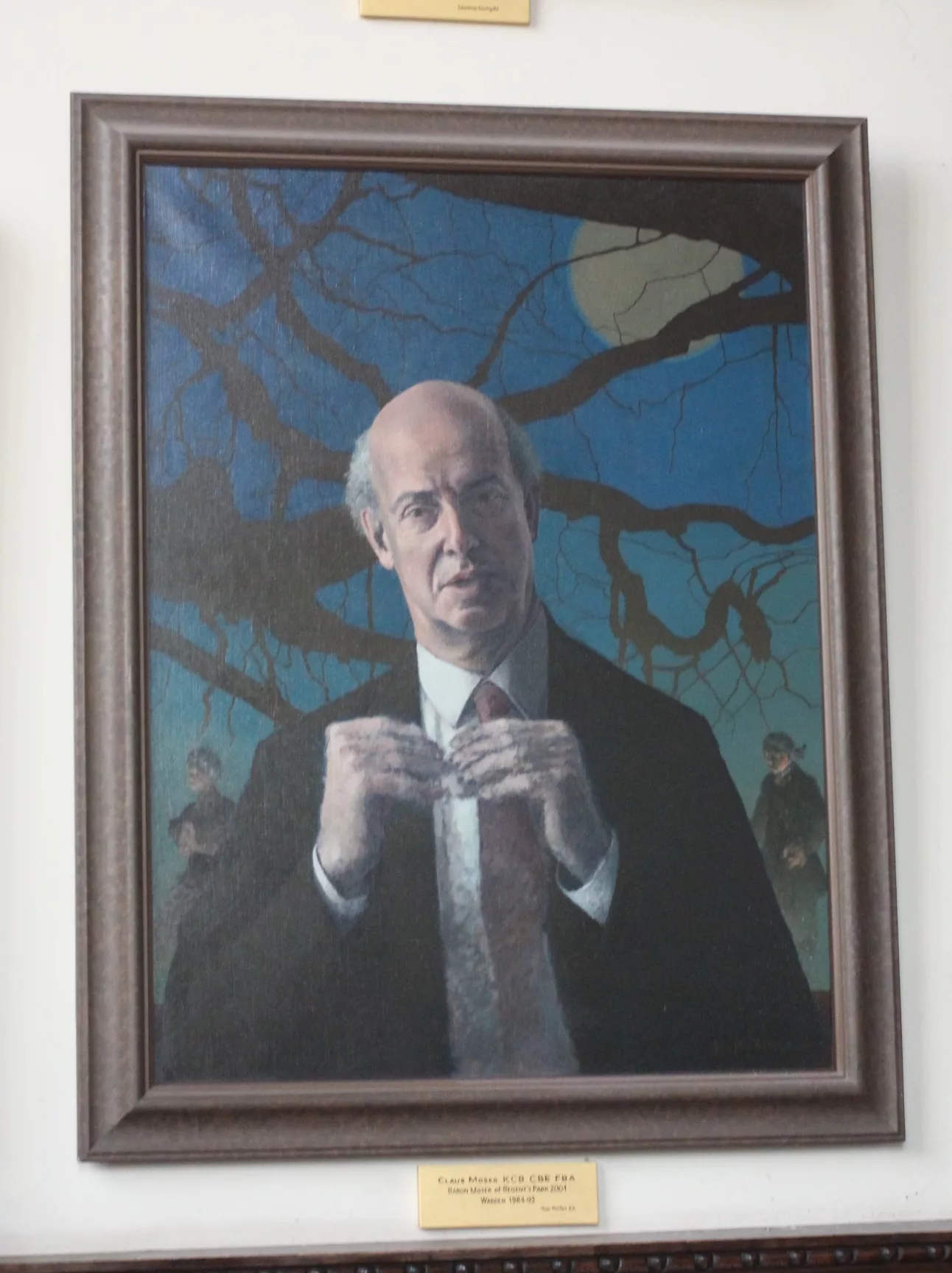

When I cook with friends at uni, I unshoulder the burden of formal dinners and confusing table etiquettes, of immaculate subfusc and formidable architecture, of glamourous lecture halls and Rousseau-esque pontifications – of everything too posh, and too white. I become myself again in our chaotic kitchen with its multi-ethnic food. Here, I’m the only Chinese person, and the only American, but that’s okay because home is no longer one specific place, but the embrace of all places.

On Chinese New Year, inshallah, I will teach my British friends to fold crescent-moon dumplings, tucking all the pieces of myself – China, America, Morocco, and England – into savoury stuffings.

– – –

After one of our potlucks, I posted a group photo of us with the Arabic word “عيلتي.” The next day, Liyanah told me that she’d drawn up a family tree of our friend group based on our personalities.

She had no idea that عيلتي meant “my family.” I told her, and we marvelled at the coincidence of how we’d both come to the same thought.

Or perhaps it wasn’t a coincidence, but that we communicated through the language of cooking.