The vac is very much here and in a new series of articles, I am bringing you the top spots in the country for a day out over the Easter break. Up first is Camden Market, a food lovers’ paradise. It makes an ideal location for a day trip with friends and is super easy to get to on the tube from central London. In between the eclectic mix of trendy unique and independent shops is the best selection of street food that the UK has to offer. The problem with all that choice is that knowing where to start can be impossible. So, I set out on a quest to unpick that dilemma. Last week I tried 15 of Camden’s most popular stalls in one day to bring you the definitive list of the places to go and the dishes to order at the home of London street food.

Tsujuri — The Matcha One

Tsujuri specialises in all things matcha. Here you can get everything from ceremonial-grade matcha tea to matcha lattes, matcha soft serve, mochi, and a mix of all three in a matcha float. For me, the matcha lattes (which don’t use ceremonial matcha) were far too earthy. The matcha tea is prepared authentically with water in a bowl but fairly expensive. I would opt for the float every time — the slush keeps the sundae light, the soft serve is deliciously sweet, and the red bean paste adds a great contrast.

Matcha Tea — £5.30, Matcha Float — £8.40, Matcha Kuromitsu Latte — £6.60

Curry Up Camden — The Indian One

Don’t be fooled by the name, Curry Up Camden offers every single Indian classic that you could possibly hope for. All curries are £10.90 or less and are served with rice, bread, or chips, and starter dishes are even cheaper. The Paneer 69 lacked a bit of flavour but the Mapas Prawn Curry was divine. Cooked in coconut milk, it remains fresh and light whilst adding a kick where you need it with some chilli. My pick of the bunch though is also the chef’s favourite, the Chicken Dum Biryani. It is more expensive at £12.90 but could easily be shared between two for a light lunch. The rice here is more flavoured than the plain ones with the curries and the chicken itself is rubbed in a huge array of spices and slow-cooked for maximum flavour.

Paneer 69 — £7.90, Mapas Prawn Curry (With Rice) — £10.90, Chicken Dum Biryani — £12.90

Funky Chips — The Loaded Fries One

You might think that you have seen loaded fries before — I am telling you that you have never tried anything like the creations on offer at Funky Chips. They offer burgers too but the main attraction is the stall’s namesake. Available at several locations, the small size is hilariously big and at the base level costs just £4.80. You can then personalise to your heart’s content with tens of different meats, cheeses, and more, and that’s before you’ve picked from one of their 11 different house sauces. I got ours with chicken, halloumi, crispy onions, Pablo Escobar sauce, and Nice Thing sauce. The result was truly ridiculous. Make no mistake, this is easily shareable among three or four and if you want to leave the market alive I don’t recommend attempting the challenge alone! As an added bonus, the chips themselves are gluten-free and all students get a free drink with every order.

Funky Burger and Fries — £12.50, Small Fries — From £4.50

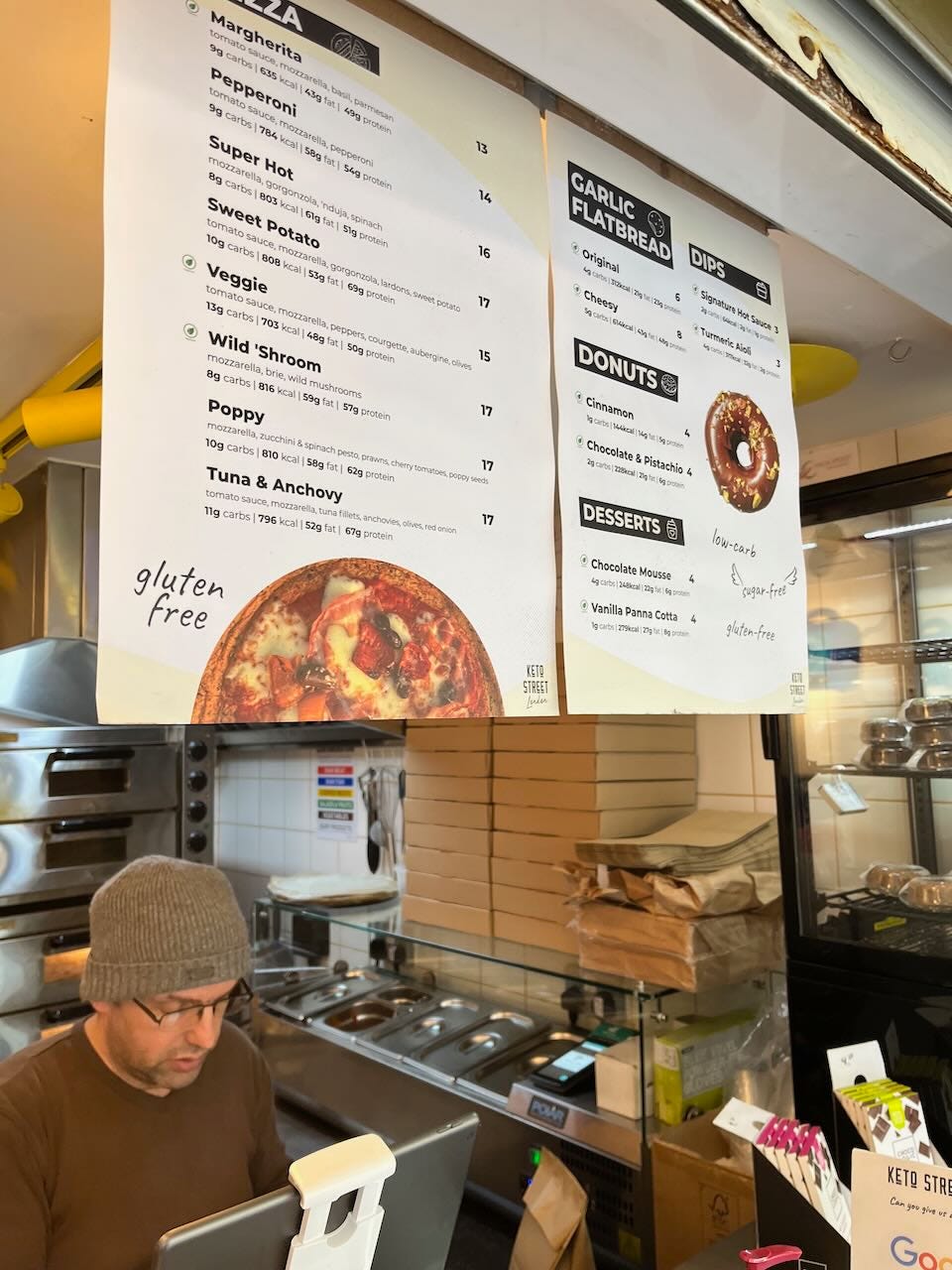

Keto Street — The Gluten-Free One

During lockdown, the Italian chef who runs Keto Street set about creating the ultimate gluten-free pizzas and doughnuts at home. Now, he has opened a stall in Camden with both of those and GF beer. Every dish is free of added sugars and low-carb as the name suggests. The pizzas themselves are incredibly expensive though for what they offer and although the thin crust has all the benefits of a crispy base, it might well leave you feeling shortchanged. And the doughnuts? Let’s just say that you can tell they are sugar-free…

Veggie Pizza £15, Super Hot Pizza — £16, Donuts — £4

NYCE — The Really Good Gluten-Free One

Admittedly, NYCE doesn’t offer the savoury dishes that you can get at Keto Street but if you are gluten-free, I suggest you just have a dessert for lunch kind of a day. Originally from the US, NYCE now has multiple sites across London and offers gluten-free soft serve and frozen yoghurt. The blueberry-elderflower packs an amazing punch and is perfect with the gf vegan marshmallows. For me, the PB Power bowl is the top choice. It has a high protein vanilla base, topped with granola, peanut butter, and banana (I also added a cheeky drizzle of chocolate hazelnut sauce for that added sweetness).

PB Power Bowl — £7.95, Blueberry Elderflower Softserve (With added toppings) — £7.65

The Cheese Bar — The Sit-Down Cheesy One

Ok, so pretty much everything at Camden Market seems to come loaded with cheese but The Cheese Bar is where to go if you are serious about it. Part of the Market’s ‘sit-down initiative’, it is a great place to escape to and feels like an oasis outside of hustle and bustle of the market itself. The bar area is beautifully modelled and there are several different themed deal nights, from raclette to fondue. As well as a 10% student discount, prices are more than reasonable for the ‘fancy vibe’ that you get here. Cheeseboards offer any choice of three of their British cheeses with crackers and innovative pairings (think goat’s cheese with Turkish delight) for £13.50, and the grilled cheeses are great value at all under £9. The Blue Cheese Raclette was my pick of things on offer with the crispy leeks and beef shin countering the powerful Young Buck cheese perfectly.

Cheeseboard — £13.50, Keen’s Cheddar and Montgomery’s Ogleshield Grilled Cheese — £8.50, Blue Cheese Raclette — £12.50

Pittabun — The New Indian Street food One

A popular street food in India, Pittabun is bringing stuffed pittas to the street food scene in Camden. The Pork Gyro option is akin to your classic kebab with all the flavour and a lot more freshness. The chicken thigh is by far the best choice here though — the lemon tahini dressing elevates it hugely and this is a spot you really shouldn’t miss for an alternative to the burgers on offer everywhere.

Chicken Thigh Pitta — £10.50, Pork Gyro Pitta — £9

Dez Amore — The Italian One

There is absolutely no shortage of pasta options in Camden but Dez Amore stands out for sure. They specialise in handmade pasta and burgers, both with classic Italian themes. With the pastas, that is more straightforward and everything you would expect is on offer from cacio e pepe to bolognese. The truffle tagliatelle was by far my favourite, available with fresh truffle shavings that really make the difference over the proliferation of fake truffle oils that have flooded the industry in recent years. The pasta itself is made in front of your eyes and superbly light, especially when with their homemade tomato and basil sauce. The Tuscan DOC burger is impossible to eat with any grace (see video!) but certainly represents value with Pecorino, onions, bacon, mushrooms, double patty, fried egg, and mayo.

Fresh Truffle Tagliatelle — £16.90, Tomato Caserecce — £9, Tuscan DOC Burger (Double patty) — £14.90

Bill or Beak — The Viral Chicken Burger One

This might be the messiest burger I’ve ever eaten but it was worth every single napkin required for the clean-up. The smashed patty beef burger option is ok but nothing special, if you come here you absolutely must go for the chicken. It contains their signature fried chicken, honey butter sauce, spicy mayo, pickles, and slaw. Simply put, you shouldn’t leave Camden without one of you trying it!

Smashed Patty Cheese Burger — £11, Honey Butter Fried Chicken Burger — £12

Chimney Cakes Lady — The Instagram Dessert Craze One

You might well have seen these all over your Instagram and TikTok feeds and I can tell you that they taste every bit as good as they look. Best of all, though, the team behind the scenes is more friendly than you could ever imagine. I went behind the scenes and saw the pair create their signature creations with all of the specialist equipment. After a trip to Hungary, they were created as a challenge set by the owner’s children. She managed to recreate the Transylvanian dessert they saw on their travels and now she has brought the craze to London. There are sweet and savoury choices on offer with all manner of coatings and fillings as well as smaller cones coated and then filled with vanilla cream. The biscuit cone was my favourite, coated in a mix of crushed biscoff and rich tea biscuits. The cream counter-intuitively adds a lightness to the sweetness that might overpower the larger cakes but I have to say that my cinnamon and Nutella one was pretty irresistible too!