This year, Human Sciences is celebrating its 50th anniversary as a degree at Oxford University. Founded in 1969, the programme saw its first cohort of students graduate in 1972 and has received a steady trickle of applicants ever since. But what actually is it? BA Human Sciences. Is it a science or is it a humanity? Or is it both? With an eclectic list of modules and a seemingly infinite number of career prospects on the course website, I wanted to know what you actually learn from the degree course and whether it really helps us to address global challenges. I spoke to three current Human Sciences students to try and find out.

Teagan Riches – 3rd Year, Hertford College

Freya Jones: Thank you for speaking with me, Teagan. Why did you choose to study Human Sciences at Oxford?

Teagan Riches: I was actually really indecisive about what I wanted to do in sixth form. All the way up until the age of sixteen I wanted to study contemporary dance, but then I got too many injuries to be able to do that. So suddenly I had to rethink everything. Then an Outreach Officer from Oxford came into my school and was trying to encourage us to apply, and my head of sixth form turned round and said, “have you thought about Human Sciences? It sounds like the perfect course for you.” At first I wasn’t sure, because I didn’t particularly want to go to Oxford, but I went to an open day and looked more closely at the course content. When I picked my unis, I applied for Biology or Genetics everywhere else but put Human Sciences here as my first choice, because it allowed me to keep both biological and social interests open.

FJ: What does a typical week look like for a human scientist?

TR: In a typical week you’ll have about nine lectures, sometimes all on completely different topics. You can go from anthropology to biology one day, and then the next day have one on geography and another on statistics. And at the same time you’ll be writing essays on human evolution and ecology. It can be really difficult in first year, because you’re getting hit by a lot of topics at once, but you get used to that. Being interdisciplinary, the different subjects are deliberately taught at the same time, because then you cab go to your genetics lecture while writing an essay about evolution and be like, wow, there’s some kind of link I could use there. And that’s the magic of it.

FJ: Do you find that having so many topics going on at once impacts your ability to specialise?

TR: It does detract from specialisation if I’m honest, but if it wasn’t done like this, it would change the purpose of the degree. They’re very clear from the outset that it’s interdisciplinary and I think this is just what we need, because being able to view things from both a scientific standpoint and a cultural standpoint means you can develop wider ideas in so many ways.

FJ: In terms of the teaching itself, and the lectures, how would you say it compares with any expectations you might have had before coming to Oxford?

TR: I didn’t know what teaching at Oxford was going to look like really, but I think the tutorials for Human Sciences are brilliant. My only sadness, which I think a lot of people share, is that we become a kind of afterthought when we’re in class with students from other courses. For example, if we’re in a biology lecture, the teachers will help the students doing biology and then they’re like “Do we have time to help the people doing Human Sciences?” So going forward, it would be nice if we could start having more dedicated Human Sciences lectures. On the other hand, it’s nice to have classes with so many different tutors because you get to meet everybody and experience lots of different approaches.

FJ: Human Sciences is celebrating its fiftieth anniversary of being a degree this year. How relevant do you think the course content is now and what do you think the degree might look like in fifty years’ time?

TR: I think Human Sciences is probably going to become more relevant than ever as we go forward, especially as we study some of the biggest challenges our generation is going to face, like climate change and food insecurity. I also think it’s important to have people who can look at these issues on multiple levels. For example, if you have doctors who do Human Sciences as a first degree and then take graduate medicine, they could bring a lot of cultural and social insight to their patients. Or someone who wants to report on climate change as a journalist would have a good grounding in science. What I will say though, is that lots of our senior tutors who’ve been around since the foundation of the degree are retiring, and they’re not being replaced. Overall there’s a lack of human scientists, which means there’s little incentive for more colleges to start offering it and there’s a fear it will die out because of lack of funding. However, I really hope the degree will grow and people will see how important it is, because we really can’t lose it.

FJ: It’s so interesting to hear this! Before doing these interviews, I’d seen Human Sciences being labelled as quite an incongruous degree, but your subject content sounds fascinating. What’s your take on these sorts of stereotypes about the course?

TR: Well, it’s true that the first thing people ask about my subject is “What is Human Sciences?”. I also agree there’s a common assumption that it’s a “jack of all trades, master of none” kind of course. But what people don’t realise is that we cover what we do study on a really deep level, albeit a broad range of things. And while there’s a misconception that it’s kind of a floater degree, prospective applicants are often really interested in it. I do a lot of Access and Outreach work, speaking to school children, and when they hear it exists, they’re usually like “that sounds brilliant”. I just don’t think it’s talked about enough.

FJ: If there was one thing you could change or improve about Human Sciences at Oxford, what would it be?

TR: I think a lot of human scientists would love it to be a four-year course, with an integrated masters, so we could actually keep our studies broader for longer. Some people are unsure how a Masters of Human Sciences would look, but lots of students take on really interesting visitations and field work anyway, which I think could make a good final year after using three whole years to get through the content. I also think Human Sciences should be offered at more colleges, so we’d have a bigger cohort for exchanging ideas.

Charlie Hancock – 3rd Year, Hertford College

Freya Jones: Thanks for talking to me, Charlie. Why did you apply for Human Sciences?

Charlie Hancock: I didn’t know it existed until I got into sixth form, but I’ve always had very broad interests and spent a lot of my school career wanting to go into sciences. Then the real world started happening, and events made me think that I didn’t want to go in a purely scientific direction. I also figured it would make sense for me to do a degree which would give me lots of areas of knowledge to draw on, because I was pretty certain by sixth form that I wanted be a journalist, and I wanted to learn things that would make me an attractive person to have in a newsroom. Essentially, I considered Human Sciences, PPE, and History and Politics and I chose Human Sciences because it had the greatest number of modules – like genetics – that I couldn’t teach myself and where I would actually need to be taught.

FJ: Thinking about the breadth of your degree, what’s it like to jump between such a wide range of topics at the same time?

CH: Short answer, not easy! You have to learn very different styles of essay writing and studying for your different papers. Genetics essays are very dry and factual, so you’re essentially just memorising facts and regurgitating them as you go along. But essays for demography or sociology are far more like your “typical” Oxford essay, and those are two of my favourite papers. But overall it’s good to have the flexibility.

FJ: How often does the degree structure give you a chance to specialise in particular areas of interest?

CH: I wouldn’t use the word specialise because I think it’s too narrow. But out of the seven papers we have to take for our finals, we only have a choice over three of them. Some of the compulsory options are really fascinating, like human ecology, and together they really show the potential of the degree. But I also wonder whether having so many compulsory papers is to try and stop us from specialising and force us to have broad interests.

FJ: What does this look like in terms of teaching? I’d imagine it can be quite hectic if your teaching is spread between multiple departments.

CH: I never counted my contact hours exactly, but I remember having two or three tutorials a week in first year, which was intense. For Prelims, it’s a lot more like a STEM subject, with some lab sessions and a lecture every day, but later on in the degree it’s definitely about striking that balance between STEM and humanities.

FJ: That sounds like quite a balance! Obviously you plan to go into journalism, are you aware of the rest of your cohort having clear career plans?

CH: I think a lot of people want to go into NGO work, for which Human Sciences would be very useful, because it teaches you about nutritional anthropology in developing countries and so on. Lots of us also have plans to go on to further study, and quite a few are involved in consulting. But I think people choose Human Sciences because it’s a springboard which introduces you to lots of different things.

FJ: That’s interesting. And as someone who knows what they want to do, how useful has Human Sciences been for your career prospects?

CH: Well frankly there are many aspects of my degree which I’m never going to use. For example, a lot of anthropological studies might satisfy my curiosity, but I’m never going to return to them. On the other hand, I’ve gained a set of skills which should be useful in the newsroom, such as being mathematically competent and knowing how to analyse datasets. It also helps you to think outside the box and make connections between different ideas, which is very useful for journalism.

FJ: Is there anything you would change about the degree?

CH: I think I’d make it more customisable. The course has some pretty impressive potential, but it’s frustrating to have so many compulsory papers and that – when you actually get to make decisions – there are still relatively few options to take. So it would be nice to see a wider range of optional papers.

FJ: How important do you think Human Sciences is as a degree, both today and going forward?

CH: I acknowledge Human Sciences is a weird degree, but I think it’s a very good thing that it exists. The basic principal of having people who are competent in both the sciences and the humanities is crucial. However, I do think the degree will have to evolve. The greatest threat to Human Sciences is that, by its very nature, we’re reliant on different departments for teaching and we’re a small course. There isn’t much impetus for colleges to start taking human scientists. Going forwards it will also have to integrate how technology impacts human lives.

Molayo Ogunde – 3rd Year, St Hugh’s College

Freya Jones: Molayo, thank you for speaking with me. Why did you choose Human Sciences when you were applying for Oxford?

Molayo Ogunde: Interesting. I think I decided to apply for Human Sciences more than I decided to apply for Oxford itself, actually. I originally applied for med school, but then I took a gap year and decided I wanted to do something which was a combination of my interests. At school, I was pushed towards medicine because I was interested in biology, but I wanted to do something else and I thought, why not give this a go?

FJ: How have you found the balance between sciences and humanities in your degree now you’re here?

MO: I think it’s largely dependent on which options you take. In the first two years of the course, there’s already quite a good balance, but in third year you can choose to concentrate more on humanities or on science. Personally I’ve tried to keep a balance with both, to explore my biological interests as well as more critical things.

FJ: How challenging is it to keep track of what I’d imagine is a very broad range of topics?

MO: It’s definitely challenging. One moment, I’m doing coding, the next moment, I’m reading about health economics, or writing an essay on anthropology. I try to structure my days so that I can delve into different topics at different times.

FJ: Do you have opportunities to go into as much depth as you’d like to in subject areas of interest?

MO: Not always, but I think that’s because we’re a three-year degree. There’s only so much you can cover, and going into the same depth as other degrees on everything would be quite intensive.

FJ: How does the quality and style of teaching compare to any expectations you may have had before coming here?

MO: I guess one thing I did expect was more lab work, but I’m not too upset about that because the course has been good regardless. It’s really nice to study with such a variety of different people and be taught by tutors from different fields. For example, you’ll get one lecturer who talks about how much he loves birds, and then you’ll be hearing what your tutor things about designer babies.

FJ: Thinking of the world beyond Oxford, how well has the degree prepared you for what you want to do personally?

MO: Well, I did a consulting internship in summer and I think it prepared me pretty well for that. Because it’s so broad, it really equipped me to manage interpersonal relationships with the people and clients I was working for. It’s also good to get more transferable skills, like a grounding in statistics, which you wouldn’t strictly pick up from, say, biology.

FJ: If there was something you could change about Human Sciences at Oxford, what would it be?

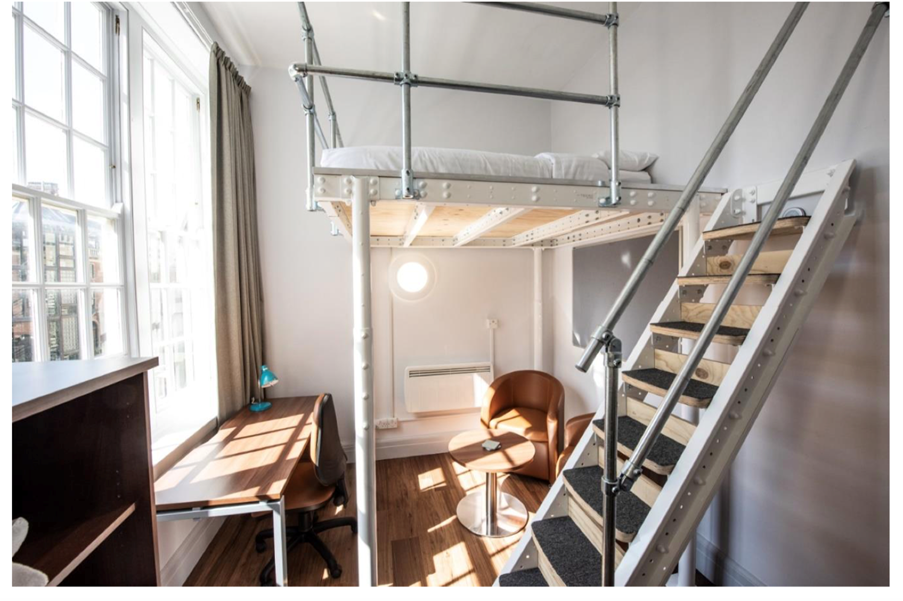

MO: To start with, I’d get a bigger building. At the moment we literally have our classes in a house, which feels a bit weird. It would also be nice to have our own consistent lectures, as opposed to just dropping into other people’s where Human Sciences isn’t really in focus. But equally, I think that’s part and parcel of being an interdisciplinary degree.

I was surprised by how much I learnt from these conversations. As a die-hard humanities student, I had my doubts about the substance of any BA with “Sciences” in the name, but HumSci really does seem rigorous, interesting, and supportive of outside-the-box thinking. The way in which interdisciplinary work (potentially a logistical nightmare) is viewed as the basis for employability and a uniquely attractive skillset was also striking. Thus, with current plans in the works for the launch of a student-lead Human Sciences Society, many hope to attract more applicants and crucial funding. Meanwhile, one wonders which course content and case studies will be used for Human Sciences in fifty years’ time.