Oxford’s colleges are all infamous for different reasons, and come with their own unique reputations and stereotypes – grand or scrappy, aloof or chaotic, satirised or beloved, glamorous or quietly dependable. What if, instead of being identified by their quads and cloisters, they were cast as famous literary characters? Christ Church College’s boastful architecture smacks of Gatsby; Keble College seems to brood like Frankenstein’s creature; and Exeter College reminds one of rebels like Jo March.

Below, I’ve matched Oxford’s colleges with a figure from ‘the canon’ in an attempt to capture, to the best of my ability, their distinctive characters, pairing architecture with archetype, and reputation with narrative behaviour.

Balliol College is Hamlet from Hamlet

Political, intellectual, and emotionally tortured. Balliol’s reputation for philosophers and prime ministers mirrors the political upheaval afflicting Shakespeare’s brooding prince.

Blackfriars is Father Brown from The Father Brown Stories

Witty, wise, and compassionate – this beloved Catholic priest is the perfect embodiment of the college steeped in theology and philosophy.

Brasenose College is Sancho Panza from Don Quixote

Earthy, humorous, and loyal to a fault. Brasenose is a hearty and sociable college, beloved by most, with a refreshing down-to-earth vibe.

Campion Hall is Father Gabriel from The Mission

Quietly powerful and deeply intellectual, this college carries centuries of history and is perfectly represented by the compassionate Jesuit missionary.

Christ Church College is Jay Gatsby from The Great Gatsby

Boasting with wealth, grandeur, and pomp. This college is Jay Gatsby personified, with its beautiful dining hall, high society, and students who cannot help but throw themselves into the spotlight.

Corpus Christi College is Mole from The Wind in the Willows

Small, understated, and quietly charming. The Corpus Pelican, a golden pelican sundial in the middle of the college’s quad, is just as whimsical as Mole’s homey energy.

Exeter College is Jo March from Little Women

Creative, ambitious, and literary, Exeter might not be the flashiest of colleges, but is surely full of heart.

Green Templeton College is Dr John Watson from The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

This practical, observant, and quietly heroic figure captures the progressive nature of the college, as well as its focus on medicine, business, and social sciences.

Harris Manchester College is Gandalf from The Lord of the Rings

Having famously warm vibes, an eclectic student body, and a touch of quiet wisdom, Harris Manchester stands out among the other undergrad-heavy colleges, and is just like the elder statesman of the Fellowship.

Hertford College is Emma from Emma

Witty, independent, and charming, just like the beloved heroine of this Austen classic, Hertford’s architecture is just as playful as Emma’s matchmaking.

Jesus College is Howl from Howl’s Moving Castle

A flamboyant, slightly chaotic Welsh wizard who is both brilliant and a tad eccentric. Plus, he has a wandering castle – what better metaphor for this tucked away college?

Keble College is Frankenstein’s monster from Frankenstein

The dramatic, gothic, red-brick college unites all that is paradoxical, and seems to generate a multitude of opinions. Some think it monstrous, others marvellous.

Kellogg College is Katniss Everdeen from The Hunger Games

Young, modern, adaptable, resilient. Kellogg can often be an underdog compared to the grandeur of some other colleges, but its modernity is also its strength.

Lady Margaret Hall is Anne Shirley from Anne of Green Gables

LMH is – just like the bold Anne – a pioneering outsider full of earnest energy. The first women’s college, it has always strived for change and progress.

Linacre College is Mary Poppins from Mary Poppins

Pragmatic and progressive, Linacre seems to take responsibility seriously, but always has a twinkle in its eye.

Lincoln College is Bilbo Baggins from The Hobbit

Compact, warm-hearted, and quietly adventurous. Tucked away on Turl Street, this college feels exactly like a well-loved hobbit-hole, with a hidden world behind its door.

Magdalen College is Mr Darcy from Pride and Prejudice

Immaculate, beautiful, and aristocratic, Magdalen can feel imposing to outsiders. However, once known, it becomes steadfast and magnetic.

Mansfield College is Atticus Finch from To Kill a Mockingbird

Mansfield is socially conscious, progressive, and justice-minded, whilst wearing its radical heart right on its sleeve.

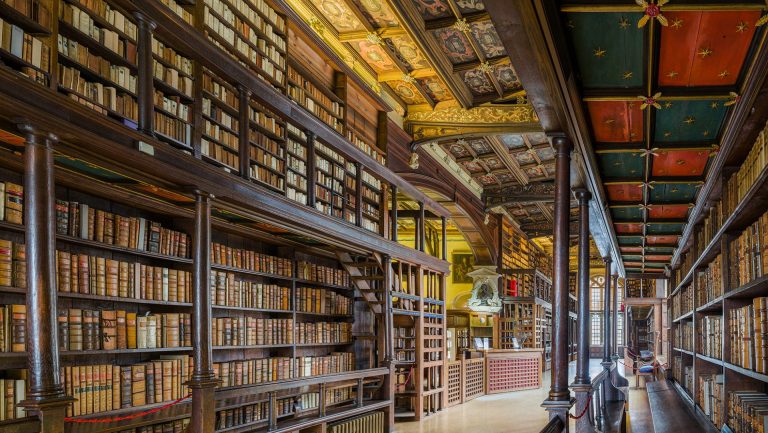

Merton College is Prospero from The Tempest

Merton is home to one of Europe’s oldest libraries, giving it its ancient, powerful, bookish flair. Known as the most academic Oxford college, it certainly resembles this wizard-like Shakespeare figure.

New College is Dorian Gray from The Picture of Dorian Gray

New embodies everything that Wilde’s protagonist stands for: eternal youth, timelessness, and beauty. It looks almost untouched by time, but has centuries of history under its belt.

Nuffield College is Piggy from Lord of the Flies

Just like the little data-driven thinker trying to hold civilisation together, this small and graduate-only college is analytical and influential, with its focus on politics and economics.

Oriel College is Sherlock Holmes from The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

Traditionalist, precise, and rather conservative, Oriel has a mixed reputation resembling the division in popular opinion about the great detective.

Pembroke College is Oliver Twist from Oliver Twist

A little plucky, small, and often overshadowed by its flashier neighbours, Pembroke is full of charm and scrappiness.

Queen’s College is Lady Macbeth from Macbeth

Regal and imposing, with dramatic architecture. The college commands the stage from its place towering over the High Street, yet entering it can prove quite the challenge.

Regent’s Park is Jean Valjean from Les Misérables

Just like the redeemed and compassionate Jean, Regent’s Park is dedicated to goodness and its Baptist principles.

Reuben College is Matilda Wormwood from Matilda

As the youngest member of the Oxford family (founded only in 2019), this college has a decisively modern ethos and is just as clever and energetic as Matilda herself.

Somerville College is Hermione Granger from the Harry Potter series

A brilliant, pioneering college with feminist roots, and therefore the ultimate symbol of brains, independence, and the Granger spirit.

St Anne’s College is Scout Finch from To Kill a Mockingbird

St Anne’s is modern, no-nonsense, and progressive, yet remains full of a curiosity and spirit that make it quite charming.

St Anthony’s College is Odysseus from The Odyssey

International and worldly. This college seems to always be travelling and telling stories. Removed from the central hub of colleges, it remains something of a mysterious outsider.

St Catherine’s College is Holden Caulfield from The Catcher in the Rye

This college is a modernist outsider. It is plain, concrete, often misunderstood or made fun of, but radically proud of its difference.

St Cross College is Phileas Fogg from Around the World in 80 Days

With its wonderfully cosmopolitan and understated character, St Cross is known for being open, collegial, and international.

St Edmund Hall (Teddy Hall) is Pip from Great Expectations

Old, a bit scrappy, and full of ambition, St Edmund Hall is always reaching upwards, yet stays cheerful and approachable.

St Hilda’s College is Jane Eyre from Jane Eyre

Principled and intelligent, St Hilda’s is a college that triumphs with its quiet strength and integrity – much like the beloved heroine of Charlotte Brontë’s famous novel.

St Hugh’s College is Dorothea Brooke from Middlemarch

Serious-minded, idealistic, and underrated. Just like this layered character, St Hugh’s character is difficult to discern – but maybe that’s just because it lies quite far off.

St John’s College is Ebenezer Scrooge from A Christmas Carol

Staggeringly rich and sometimes resented. St John’s is undoubtedly one of the wealthiest colleges in Oxford, but its funding for scholarships and outreach work gives it a philanthropic heart.

St Peter’s College is Willy Wonka from Charlie and the Chocolate Factory

Quirky, colourful, and on the smaller side, this college lies hidden away behind a wall and is therefore full of surprises.

Trinity College is Tom Sawyer from The Adventures of Tom Sawyer

Incredibly adventurous and playful, this beloved college always seems to be at the centre of fun and mischief.

University College (Univ) is George Knightley from Emma

Steadfast, dependable, friendly, and wise, but less showy than some other colleges, Univ is a High Street presence all are glad to see.

Wadham College is Orlando from Orlando

Orlando – with their gender-fluid, timeless, and artistic character – is a near-perfect symbol for Wadham’s radical and progressive tradition, and famously strong LGBTQ+ identity.

Wolfson College is Tony Stark from the Marvel comics

Famously progressive, interdisciplinary, and informal (having no high table or gowns), this college pushes boundaries and breaks conventions just like the beloved superhero.

Worcester College is Mary Lennox from The Secret Garden

Worcester’s lush and dreamy gardens feel precisely like Mary’s discovered paradise, and are just as charming as the curious protagonist herself.

Wycliffe Hall is Aslan from The Chronicles of Narnia

Wycliffe is one of Oxford’s Permanent Private Halls, known for being evangelical, deeply theological, and community-oriented, whilst prioritising debates and social activism.