From his office in the Clarendon building on Broad Street, Richard Ovenden calls libraries “the infrastructure of democracy.” These words are spoken with the authority of someone who clearly sees preservation not as nostalgia, but as a duty – a form of stewardship for knowledge itself. As the 25th Bodley’s Librarian, Ovenden is custodian of one of Europe’s oldest libraries, and he makes a simple but radical claim: that protecting the archive is an act of public service.

It’s a belief that clearly shapes every part of his work at the Bodleian, where the boundaries between scholarship and politics are never entirely clear. As Ovenden admits, the archives are “capital P political” – home to the papers of prime ministers as well as the official archive of the Conservative Party, the records of Oxfam and the anti-apartheid movement. But he also recognises that every decision about what to preserve is, in itself, political. “Archivists are human beings”, he says; while they follow collection development policy, they are inevitably guided by their own interests and conflicts. His own interest lies in photography – a passion that has shaped recent acquisitions and exhibitions, most notably ‘The Camera Helps’ at the Weston Library, the first retrospective of the works of British social documentary photographer, Paddy Summerfield. As he puts it, “humans who have worked in the Bodleian for over 400 years have all played their role”, and this, too, is part of its lineage; his personal curiosity will undeniably leave a lasting institutional trace.

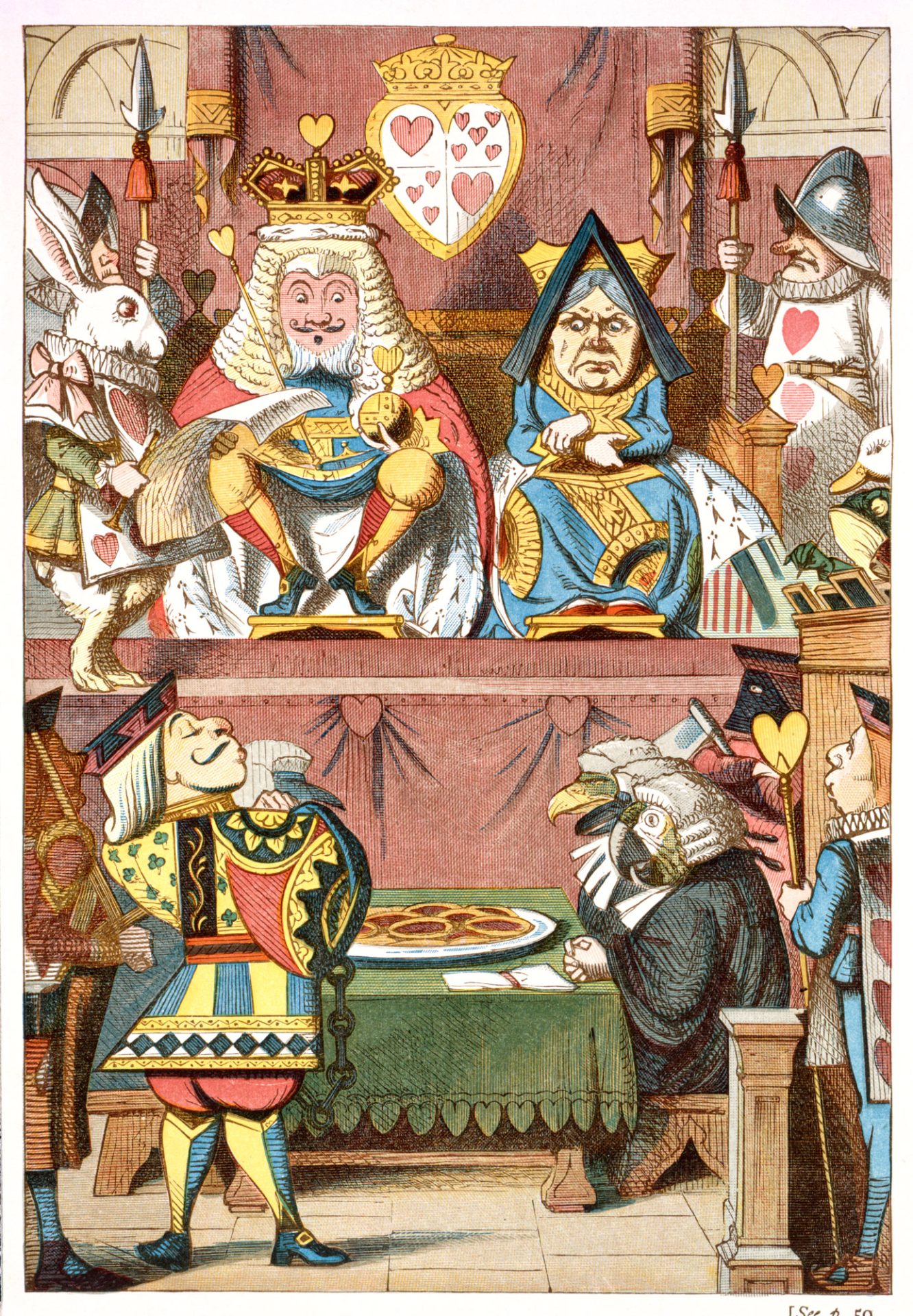

Ovenden is deeply conscious of the Bodleian’s long and sometimes fraught history. The library first opened its doors to the public on the 8th November 1602, celebrating its 423rd birthday earlier this month. Decisions made by predecessors continue to shape the archive today: historical collection biases, for instance, meant that works by some major women authors of the 19th century were turned down. As Ovenden admits, the decision to reject the first-editions of Jane Austen, Mary Shelley, and the Brontë sisters, “totally haunts me” hundreds of years later. These gaps still resonate within the collection, reminding us that archives were never neutral, and that each generation of librarians leaves its imprint.

These choices about what to preserve are rarely straightforward. As Ovenden explains, there’s always an element of serendipity in what survives – a “supply and demand equation”, as he calls it, that relies as much on timing and luck as on policy. Occasionally, this can decide whether something is lost forever, as with the collection of glass-plate negatives acquired by the Bodleian from the Old Royal Observatory ten years ago. Nearly discarded, they were saved after a quick decision and are now being digitised with the Paris Observatory – a model for how the Bodleian collaborates internationally to preserve vulnerable material. Stories like this illustrate how easily the boundary between loss and survival can blur – and how much of an archivist’s work still rests on timing.

This sense of uncertainty runs through much of Ovenden’s work. With over 13 million printed items, and a rough total count of 23 million items, he admits that “there’s hidden material in there” – documents, images, and artefacts that haven’t been uncovered yet. It’s clearly a prospect that excites him and one that he sees as central to the Bodleian’s future – particularly as technological developments allow even well-known items to be seen in a new light. Through the ARCHiOx project, alongside the Factum Foundation, the Bodleian has been experimenting with photometric stereo technology to capture the surface of manuscripts in microscopic detail, revealing indentations and marks invisible to the eye. One of the most brilliant discoveries has been to uncover faded etchings and doodles in an 8th-century manuscript – inscriptions that hint at a woman named Eadburg, probably a nun, drawing little characters; not unlike students in a boring tutorial. These hidden marks, invisible to the naked eye, illustrate how new tools are reshaping what ‘preservation’ means.

Yet as much as technology allows us to uncover the past, it also forces reflection on the present. Ovenden tells me about his lunch earlier that day, where he spent some time discussing social media archiving – how future scholars might want to use the material we produce today, and therefore how we should preserve it. It’s a question that clearly fascinates him partly for its practical implications and partly for what it reveals about the assumptions we make about ourselves. He agrees that “we always think of the current time as the best”, but history, he suggests, teaches otherwise. The choices we make about what to keep – the tweets, the videos, the messages – will shape what the future can know about us, and we have to make those choices now, with imperfect insight. Beyond its value to researchers, this kind of preservation has tangible consequences: records of online communication are already being used in war tribunals and human rights investigations. The challenge, he explains, is that we must make our best estimations of what will be wanted in the future – “and we almost always get it wrong.”

“I’m a preserver”, he says. It’s not a grand statement, but it captures something central to his work: the quiet insistence that some record, however uncertain, is always worth keeping.

That instinct to preserve extends beyond the Bodleian. In recent pieces in The Observer, Ovenden has repeatedly returned to the question of what happens when societies fail to protect their records – when libraries are closed, books removed from shelves, or archives left to decay. His concern is not nostalgia but accountability. He has written about the closure of public libraries across Britain – almost 200 since 2016 – which disproportionately affect the most deprived areas of the UK, arguing that they have a direct impact on the freedom of readers. Public libraries, he reminds us, are “the infrastructure of democracy itself”, places that allow everyone to “read freely from well-stocked shelves”, regardless of background or means.

In another piece, Ovenden turns his attention to the United States, where libraries have become “the frontline of the battles over knowledge.” He charts an alarming rise in book bans and political interference – librarians dismissed, data deleted, and the heads of major national institutions forced out. What connects these episodes, he suggests, is not censorship but a deliberate effort to control the public record. As he writes, the “war on libraries” is a warning of how fragile the principles of open access and free inquiry can be. Across both pieces, Ovenden’s message is clear: when the institutions that safeguard knowledge are undermined, democracy itself is weakened. The Bodleian, the public library, and the digital archive all stand on the same foundation – the belief that access to information is a public good, not a privilege.

The Bodleian’s reach, though, extends far beyond Oxford’s colleges and quads. As Ovenden is quick to point out, it isn’t simply a university resource, but a national one – a library of legal deposit, holding a copy of every book in the UK, and a partner to hundreds of institutions worldwide. Its collections belong not just to scholars in Oxford but to anyone seeking to use them. “The library is more than just an immediate resource for the academic community”, he says in his measured way, describing partnerships with museums, schools and archives that make its vast collection more publicly accessible.

That sense of duty carries particular weight in Oxford, where some of the most deprived communities in the country sit just a short distance from the dreaming spires. Few students ever see that contrast, but Ovenden is acutely aware of it. For him, the Bodleian’s responsibility doesn’t end at the edge of the University. Much of its recent work has focused on finding ways to open up the collections to those who might never otherwise encounter them, through free public exhibitions in the Weston Library to collaborations with local schools, and digital projects that allow people around the world to access material from the reading rooms. Beyond that, innovations such as “tea trolley teaching” designed to provide library services to local hospitals, and the ‘Oxford Reads Kafka’ project of last year, reflect his belief that libraries are not static institutions but “palaces for the people”. As he puts it, “we have a duty as a place of preservation and dissemination of knowledge” – a warning that the work of the Bodleian is not only to safeguard the past, but to ensure that it continues to speak to the present. Therefore, the act of preservation itself is ultimately about the future, not the past; “we are guardians of facts and truth; rights of citizens; and identities of communities.”

When I asked Ovenden about these ideas of legacy – what he hopes will endure beyond his tenure – his thoughts turned immediately to one of the first collections he helped acquire: the Abinger Archive, the papers of Mary Shelley and her parents. At its heart is the manuscript of Frankenstein, accompanied by a series of journals between Percy and Mary Shelley, including the haunting Journal of Sorrow, which Mary kept following Percy’s death in 1822. “Fantastically interesting and important”, he reflects. Being involved in that acquisition, to fundraising to publishing and mounting exhibitions, clearly left a lasting impression on him. It was a concrete reminder that the choices librarians make – what to save, how to preserve and present it – determine what survives, what is remembered. For Ovenden, legacy doesn’t appear to be about monuments or titles, but about ensuring that the traces of human thought and experience – especially those vulnerable to loss – remain accessible and meaningful to future generations.

That sense of responsibility extends into his reflections for students. “I was a history student at Durham and here I am as the Bodley’s Librarian”, he says, almost matter-of-factly, a reminder that curiosity and persistence can take you far. He describes the current moment as a fascinating, if challenging, time to work in the “profession of knowledge” – particularly as access to information is increasingly shaped by commercial platforms and private “superpowers.” This makes the role of librarians and archivists all the more vital: the decisions they make about what to preserve and how are not just about collections – they shape how society remembers, questions, and understands itself.

Even beyond professional considerations, Ovenden’s personal reading life offers insight into how he thinks about value and preservation. When I asked him for a single favourite book, he hesitated and then asked if I could possibly stretch to two. The first was The Lord of the Rings, which he fell in love with as a teenager after it introduced him to long-form prose and the pleasures of collecting. The second was Olivia Manning’s Balkans Trilogy, which he describes as “the most brilliant writing… more than comfort reading, it’s a balm to the soul.” For Ovenden, these personal attachments are inseparable from his work; they are a reminder that libraries exist not only to safeguard facts but to preserve the imaginative and emotional threads that connect readers across generations.

Sitting with Richard Ovenden, it becomes clear that the Bodleian is more than just a repository of books and manuscripts; it’s a living testament to the choices societies make about what to remember and what to forget. His favourite books, the ones that first drew him into reading and collecting, serve as a quiet reminder that preservation is about curiosity, imagination and connection, as much as it is about facts. Underpinning it all is the conviction that libraries are, in his words, “the infrastructure of democracy” – a place where knowledge is protected, shared, and made available to all, not just the few. This conviction feels more urgent than ever in a moment where both libraries and democracy are under pressure – from political interference, book bans, and the erosion of public access. His work is a reminder that preservation is not just about safeguarding the past, but about defending the foundations of an open society. In the choices he makes, from rescuing fragile manuscripts to shaping national and international collections, he demonstrates that the survival of knowledge – and with it, the health of democracy – depends on vigilance, curiosity, and the quiet insistence that some record, however vulnerable, is always worth keeping.