According to the NHS, a migraine is usually identified by a moderate or severe throbbing pain on one side of the head. It is a complex condition with a wide variety of symptoms, including sensitivities to light or sound. It is a common health condition, with 1 in 5 women and 1 in 15 men affected in the UK.

It is also a very disabling one: globally, migraine is ranked as the seventh most disabling of all diseases, being responsible for 2.9% of all years of life lost to disability. The WHO classifies severe continuous migraine as among the most disabling illnesses, in the same level of disability as dementia, quadriplegia and active psychosis – rated higher even than blindness. The financial burden of migraine on the UK economy is conservatively estimated at £3.42 billion per year. Yet research into migraines is the least publicly funded of all neurological illnesses relative to the economic impact.

To better understand the condition and what it feels like, we interviewed four Oxford students to hear about their migraine experiences. Their answers show just how diverse each experience of migraine is, although they are of course not representative of the disease as a whole.

Phases of a migraine attack

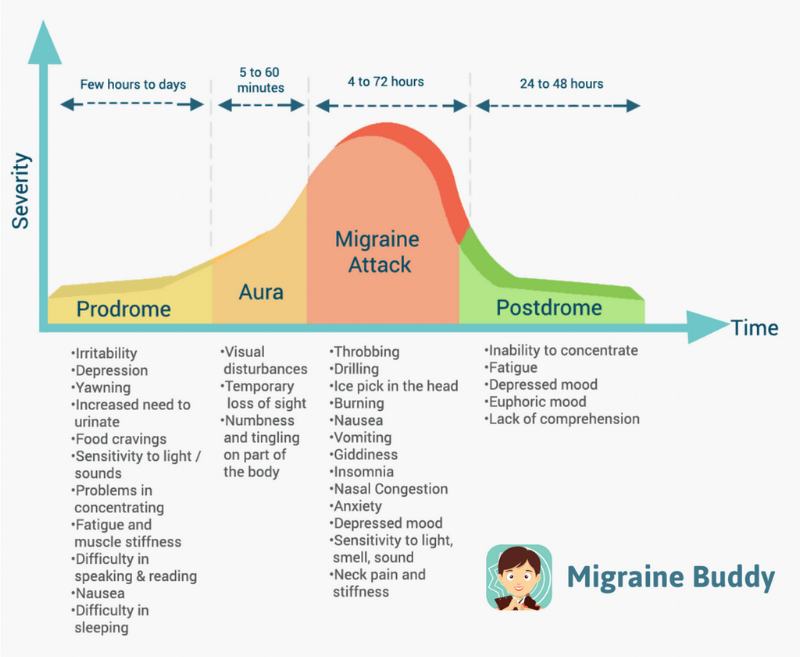

Migraine attacks are often split into four phases, classified as prodrome, aura, headache, and postrome. However, there is not one “normal” migraine attack. Some people experience only one or a few of the phases, or experience overlap.

The prodrome, also known as the “pre-headache” is the first phase of the attack. It can begin up to 48 hours before the others and often acts as a warning sign that an attack is coming. The symptoms can be quite unusual – the most common ones are changes in energy levels (both hyperactivity or fatigue), changes in mood, sensitivity to either light or sound, neck pain and stomach issues such as constipation or diarrhea. Around 80 percent of migraine sufferers experience this phase.

The second phase is the aura, which manifests itself through a change in senses. It commonly lasts an hour and can overlap with the prodrome and the headache phase. Sight changes are the most common symptom; one of the students interviewed reports seeing “weird, fuzzy things” and losing sight in one eye. Seeing stars or blurred vision are also common. Other senses can be affected as well, with another student reporting numbness in their feet, as well as vertigo so bad they fell over. Others also experience changes in hearing such as tinnitus. Around a quarter of migraine sufferers experience this phase. Some only experience the aura without the other phases, which is called a “silent headache”.

The third phase is the most well-known: the migraine headache. It can last from 4 to 72 hours, and is generally characterised through a pulsing or throbbing pain in one side of the head. Although the level of pain varies, it can be severe, unbearable and completely debilitating, with over-the-counter medication like ibuprofen or paracetamol usually not being enough. “I remember thinking I was done for” was Rowan’s response, telling us that she had been unable to get a glass of water and had received codeine in the hospital at 12 years old. Frequently, this is coupled with nausea and vomiting, as well as vertigo.

The final phase is the postdrome – aptly called a “migraine hangover” by the tracking app Migraine Buddy – in which many people feel drained and exhausted, although some report euphoric moods. “Being in that much pain is just exhausting”, Megan told us, while another student mentioned that she was in bed for two days after the headache.

Treatment and triggers

Migraines are thought to be the result of abnormal brain activity. The causes of this activity remain unclear, but in many cases there is a genetic connection. Rowan told us that both her grandmothers as well as her mother suffered from migraines.

There is no cure for migraines, yet there are a number of symptom-relieving medications. Common medication includes over-the counter painkillers, such as aspirin or ibuprofen. A migraine specific class of drugs called triptans works by using Serotonin to constrict dilated blood vessels. However, triptans have strong instant side effects, and can lead to dizziness and drowsiness. Preventative treatments may help the frequency of migraines. They include medications such as antidepressants, beta-blockers and new specialized CGRP pathway monoclonal antibodies.

Many migraine sufferers also try to avoid “triggers” – factors which increase the likelihood of a migraine attack. Emotional and physical triggers are common. Rowan described tiredness and stress increasing the likelihood of an attack, and noted getting more attacks “when in Oxford”. Medication, eating habits and environmental surroundings can also be a trigger. Trudy reported not having been allowed on the combined contraceptive pill due to her migraine condition, while Michael suspected his eating and sleeping habits may increase his migraine frequency. Alcohol, cheese (casein) and coffee (caffeine) are some of the most common triggers. Megan reported “noise and light sensitivity” as well as “probably [getting] triggered” when in “crowded spaces”.

Impact on personal and academic life

The impact of migraines on people’s lives are as diverse as the palette of symptoms. Trudy told us she doesn’t take golden hour selfies to avoid specific light sensitivity triggers. Megan shared the impact of migraines on her work routine, saying that while “last year, [she] could pull all-nighters for an essay” she now finds that more than six hours of work lead her to “crash the following day”. Rowan described the uncomfortable condition of never knowing when one will have an attack. Academically, it is “hard to take two days out … without notice” and personally, she stated that “the anxiety is notable”.

COVID-19 restrictions have had a net negative impact on those suffering from migraines, finds a study published in The Journal of Headache and Pain, due to difficulty in getting access to medications and doctors as well as increases in stress. A study conducted by migraine buddy over 14 500 of its users found over 70% to have secondary health conditions, with 82% reporting depression, and 50% reporting anxiety. Isolation, higher stress levels and uncertainty caused by the pandemic can all negatively impact these conditions.

For the students we talked to, the impact has been varied. “The amount of screen-time is really bad” Megan told us, “But there’s no way I can cut it out”. Michael has only had migraines since the start of the pandemic, and wondered if “maybe it’s got something to do with it?” But restrictions also have a psychological impact. One student shared how isolation can make physical symptoms feel worse.

We asked the students what they would like others to know about migraines. All of them responded saying that migraines are not just headaches. Quite aptly, Michael said “a headache is just one symptom of it”. Megan wished there was more awareness for the severity of migraines. She shared “friends often just think “pop a few paracetamol, it will be alright’” when in fact, “[they] utterly wipe you out”. On days with an attack, she told us, it’s best not to assume how one can help, but simply to ask. For anyone seeking to help sufferers, communication is key – and as Megan notes it is often enough “to be there and be supportive”.