The University of Oxford has continued to offer a scholarship in conjunction with the Chinese Ministry of Education, which requires recipients to “support the leadership of the Communist Party of China” and “love the motherland”, as other universities around the world have cut ties.

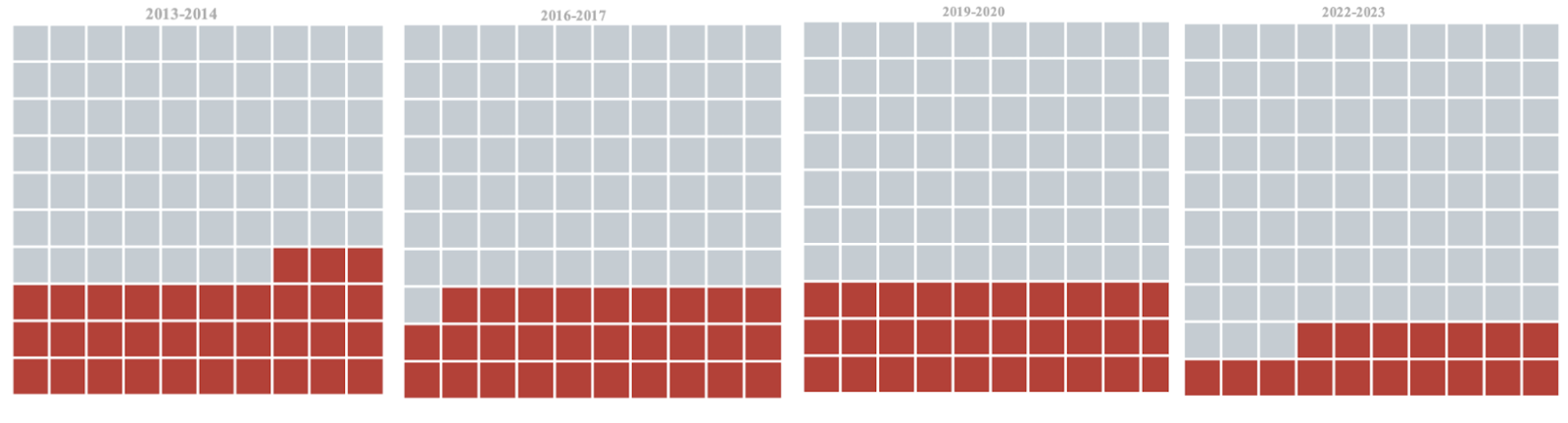

The scholarship, run by the China Scholarship Council (CSC) funds up to 20 Chinese students per year in DPhil programmes at the University. In 2023, the CSC awarded approximately 646 placements across 26 British universities.

Globally, CSC scholarships have come under scrutiny, with multiple universities in the USA and Europe breaking off relations with the programme. The University of North Texas abruptly ended their relationship with the Scholarship Council in 2020, requiring affected students to return home immediately. Negative sentiment towards the programme further intensified in 2023, when a number of European universities across Germany, Sweden, Denmark and the Netherlands severed ties with the programme.

Following Cherwell’s recent investigation into Oxford University’s financial relationship with China-linked institutions, the CSC scholarships stand out for their discrepancy with the University’s commitment to safeguard the freedom of speech of its students.

China Scholarship Council and Oxford University

Costs of China Scholarship Council-University of Oxford Scholarships are shared between the University of Oxford and the Chinese Ministry of Education via the China Scholarship Council. The two institutions jointly cover 100% of scholarship recipients’ course fees, living expenses of at least £19,237 for up to 3.5 years of study, and one return flight from China to the UK.

The award is available to students in full-time Doctorate in Philosophy (DPhil) programmes at the University, who are also residents and nationals of the People’s Republic of China. Students must first secure an unconditional offer from Oxford University before undergoing the selection process of the CSC, who determine scholarship recipients.

CSC Criteria and freedom of speech

“Basic requirements for applicants,” as defined by the Chinese Ministry of Education include that they must “support the leadership of the Communist Party of China”, “love the motherland”, and “hold correct world views and stances”.

It is unclear how these requirements are assessed, however, Article one of the current guidelines sets out to “thoroughly implement Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era.”

In describing the “selection method”, the guidelines further outline that the applicant’s “nominating unit” must “strictly assess” the applicant’s political ideology and submit an evaluation to the CSC. Nominating units include most universities in mainland China, government ministries, and provincial governments. Listed among them are six of the‘Seven Sons of National Defence – a set of Chinese universities with suspected heavy ties to the People’s Liberation Army.

The University of Oxford does not have involvement in the vetting and selection process after a student’s admission to the University.

Beyond the initial selection process, the CSC may continue to enforce its requirements throughout the duration of the scholarship through secret contracts, originally uncovered by a Swedish newspaper in January 2023. The contracts stipulate that recipients must nominate two guarantors, usually close relatives, who are bound to repay the whole scholarship, plus additional financial penalties, if the recipient breaches the terms of the agreement. Breaches include prematurely ending one’s studies, failing to return to China after the study period, and, more broadly, “engaging in acts that damage the national interest”.

Under the University’s recently approved Code of Practice on Freedom of Speech, it affirms that “freedom of speech and academic freedom are central tenets of university life and must be robustly protected.” Likewise, the provisions of the UK’s Education Act of 1986 imposes the duty to “ensure that freedom of speech within the law is secured for members, students and employees of the establishment and for visiting speakers.”

A spokesperson for the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg (FAU) in Germany, who cut ties with the programme in 2023, stated: “Under these contracts CSC scholarship holders will be unable to fully exercise their academic freedom and freedom of expression as stipulated under German Basic Law”, and determined the scholarships were “antithetical with [their] kind of values of academic freedom.”

What now for Oxford?

The University’s wider relationship with China-linked institutions may be revised even beyond this specific scholarship after the upcoming Chancellor’s election. Former Chancellor, Lord Christopher Patten, previously cautioned that “we actually have to do our part so that we don’t [see] the erosion of our values in higher education,” regarding the risks faced by Chinese students.

Current candidates to the chancellorship have expressed markedly different views of the future of Oxford’s continuing relationship with Chinese institutions. Regardless, the possible implications of the CSC scholarship on current Oxford University students must not be neglected and the University’s next steps are currently under significant attention.

The University of Oxford said in response: “Oxford welcomes applications for postgraduate study from students around the world through a highly competitive admissions process – any successful offer to study is made entirely independently of scholarship awarding bodies.

“All Oxford University research and teaching is academically driven, with the ultimate aim of enhancing openly available scholarship and knowledge. We take the security of our academic work seriously, and work closely with the appropriate Government bodies and legislation. The University is fully compliant with the government’s Academic Technology Approval Scheme (ATAS) that requires research students from some nations to apply for an ATAS certificate if their research is in certain sensitive subjects.”

(Appendix) Cherwell Translation of Relevant Guidelines

“Chapter 1 – General Provisions”:

“Article 1: Thoroughly implement Xi Jinping Thought on Socialism with Chinese Characteristics for a New Era, provide talent support for the comprehensive construction of a modern socialist country, cultivate and reserve talent for accelerating the construction of an important global centre of talent and a highland of innovation, and build a platform for cultural exchange between China and foreign countries for building a community with a shared future for mankind.”

“Chapter 4 – Application Conditions”:

“Article 7: Basic requirements for applicants

1. Applicants must support the leadership of the Communist Party of China and the socialist system with Chinese characteristics, love the motherland, be of good character, abide by laws and regulations, have a sense of responsibility for serving the country, society and the people, and hold correct worldviews, life stances and values.”

“Chapter 5 – Selection Method”:

“Article 11 The nominating unit shall review the application materials and has the right to reject any application that is untrue, inconsistent or does not meet the requirements. The nominating unit shall also strictly assess the applicant’s political ideology, teacher ethics (or conduct and academic style), and provide an evaluation of these in the unit recommendation field on the main application form.”

(These translations are drawn from the “Guidelines for the Selection of Students to Study Abroad under the National Scholarship Fund”, and were made using an online translation software, similar translations of the past 2023 guidelines may be viewed in the UKCT report on the China Scholarship Council.)