When you find yourself locked in a stranger’s car, alone, behind an MOT station 30 miles away from college, half an hour until your tute; something’s gone wrong.

Frustrated by my pedestrian existence, I decided to buy a bicycle. What I didn’t know was that this decision would take me on a very Oxford odyssey: encounters with angle-grinders in Garsington, thinly veiled hostage negotiations in a field in Abingdon, and a chat with a 9 year old about the Nigerian Naira’s dependence on petroleum exports.

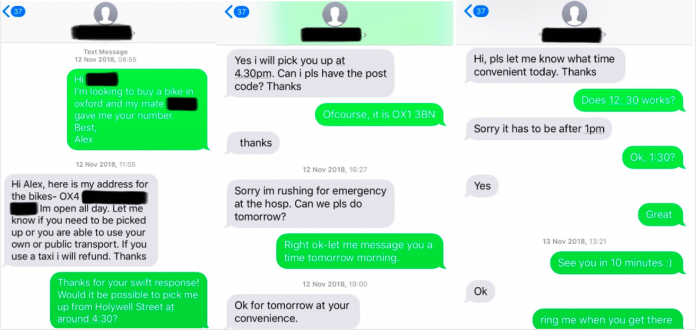

I got Jeremy’s number from a mate in college. Jeremy was evidently the go-to man, the real McCoy. I was assured that he had sold somewhat functional bikes to at least three vague acquaintances. They were also cheap. With these strong endorsements, and negative 1.5k in my Santander account, I boldly sent off my first text.

“Hi Jeremy, I’m looking to buy a bike in Oxford and my mate X gave me your number. Best, Alex”.

3 hours later, the cogs of Jeremy’s tightly run global business empire whirled into action:

“Hi Alex, here is my address for the bikes – OX4 XXX, XXXXX Road. I’m open all day. Let me know if you need to be picked up or you are unable to use your own or public transport. If you use a taxi i will refund. Thanks.”

Professional. Responsive. Transparent. Flexible. Generous. What else should I have expected from Oxford’s premier bike merchant? I scoffed at my initial hesitation to contact him; I was in the hands of a pro. I googled the address and saw that it was 15-minute drive out of Oxford. It was too far to walk, so I had a choice: the generous offer of a refundable taxi, or being picked up? I eventually opted for the latter, in a bid to strengthen my position in subsequent price negotiations. Also, since his job was literally selling transport to people because they had no other means of traveling, asking for a lift couldn’t have been an uncommon request.

“Thanks for your swift response. Would it be possible to pick me up from Holywell Street at around 4:30?”

“Yes I will pick you up at 4:30pm. Can i pls have the post code? Thanks” – I admired his stylised informality: selective decapitalisations and general aversion to punctuation. Every interaction exuded confidence and a relaxed manner indicative of vast experience.

At 4:27pm a text comes through: “Sorry im rushing for emergency at the hosp. Can we pls do tomorrow?”

An emergency! And at the hospital! How dreadful! I needed a cigarette and a lie down before I was able to compose a response. I eventually found solace in his confidence that we would be able to “do tomorrow”, since it at least implied that the medical emergency was not life threatening. I messaged him the following morning and after minimal back and forth, he arranged to pick me up at 1:30pm.

At 1:42pm a black Honda (whose back window had been repaired/replaced with cling film) eventually screeched to a halt outside New College plodge. It was at this moment I had my first inkling that this bike deal might not go as smoothly as I had hoped. But I nodded at the driver and confidently got into the (bicycle) dealer’s car. (Full disclosure: I also took a furtive photo of the car so I could lecture my friends on not judging books by their covers whilst they salivated over my gleaming bike.)

The 15 minutes flew by. He gave me a potted history of his life: his childhood in Lagos, his wife, his children, and his aspirations to graduate from a masters programme next year. I was inspired by his story and chatted with an ease I have failed to muster with any hairdresser or trained psychotherapist since. To my disappointment he made no mention of yesterday’s ‘accident’, but this modest reticence only added to my admiration of his resilience and professionalism.

Eventually the car stopped, and I was somewhat surprised to be led through the front door of a small suburban house. It only got stranger from there. He proceeded to guide me through to the back garden of what he now referred to as his home, where I was greeted by the sight of over 300 bicycles. Each bike exhibited a different stage of decomposition: most of the frames were missing at least one wheel whilst others had surrendered to rust decades ago. Presumably some were also camouflaged by the tetanus-riddled fauna of spokes, chains and brake wires. Through this metallic morass, Jeremy nimbly waded. He plucked out one bike (or most of it) after another until he found one which I liked. At a distance of 10 metres, I fell in love with a battered old racing bike frame, mottled in chipped sunset paintwork. The fact it was missing both front and back wheels phased neither me nor Jeremy, who set about finding suitable substitutes. Within minutes he had assembled a beautiful new mongrel before my eyes, never before ridden. I was encouraged to take it on a ‘test drive’.

I hadn’t ridden a bike regularly since I was 5. I am naturally lanky and malcoordinated. I will also do anything to avoid a situation in which I am publicly seen to be making a fuss. This cocktail of hamartia meant that the ‘test drive’ consisted of me wobbling along the pavement for ten metres, falling off whilst trying to disembark, and then blurting out “it’s perfect, I’d love to buy it”. He asked for £80, I offered £50. We met in the middle at £65 and shook hands. This might have been where the adventure ended had there not been one further, minor wrinkle to be ironed out.

On inspecting the bike more closely, I discovered a unique feature which Jeremy had neglected to advertise: there was a “kryptonite D-lock” still secured through the bike frame. But before I could raise an eyebrow, Jeremy anticipated my fears and reassured me that the bike was an old one of his brother’s, and he had simply lost the key. Out of the 300 bikes in his back garden, the likelihood that I should have picked out a family heirloom seemed like an extraordinary piece of fortune indeed. However, without waiting for my response, Jeremy immediately started to search for tools to remove the lock, with a speed and alacrity which confirmed that no impediment would prevent this sale from going ahead. On even closer inspection I noticed that the D-lock was not only attached to the bike frame, but also to another ring of metal–similar to the sort that are sometimes nailed onto walls for cyclists to secure their bikes. A cynical observer might claim that the bike looked like it had been forcibly ripped from the side of a building.

From the comfort of your lockdown boudoirs, I imagine it is easy for you to say what you might have done instead. I promise you it is much harder when you are actually in a man’s kitchen, with no alternative means of getting back to college, whilst he road-tests various weapons from his power tool arsenal in front of you. It gets harder still when one of his children comes downstairs and makes you a cup of tea whilst you wait.

After 15 minutes of fruitless angle-grinding, bashing and hacking, the ever-resilient Jeremy devised a new plan. He explained that he had ‘friends nearby’ in possession of the requisite tools to remove the lock. At a certain point you just have to accept that you are in too deep to bail. So, once again, I boarded the Honda, bike in tow, and went to meet Jeremy’s ‘friends’.

Jeremy’s description of ‘nearby’ turned out to be as flexible as his conception of what constituted the saleable condition of a 2nd hand bike. We drove for a further 30 minutes, deeper and deeper into the Oxfordshire countryside whilst he elaborated on his political leanings. I was interested to discover he was a “One Nation” Conservative and an ardent advocate for corporal punishment. Halfway through his assessment of the Thatcher administration, I spotted a sign saying that we were passing through Garsington. Three turns later, he pulled up behind an MOT garage. Springing out of the Honda, Jeremy whistled at his friend who slid out from beneath a car, and the two of them wheeled my bike around a corner into the sunset, leaving me locked in the car, alone.

After 40 minutes with no sign of man nor bike, I shared my live location with a friend on facebook along with a signed will that any remaining organs should be donated to science.

However, once again, my fears were unjustified, and our returning hero Jeremy rolled into sight. He proudly encouraged me to examine the recently unfettered bike and asked me if I was happy with it. As a prisoner in his car, parked on the private land of his ‘friends’ ’ MOT station, I did not think it polite to demur.

3 hours after Jeremy originally picked me up, I was returned to Holywell Street. 24 hours later, the bike’s rear hub decided to stop working. Naturally this happened whilst negotiating the Cowley Roundabout, calculated by the Department of Transport to be “the Second Most Dangerous Roundabout In Britain”. The bike is now rusting in my garden instead of his. If you recognise any of its parts (the wheels don’t match so it must have a minimum of 3 previous owners) then let me know and I can return the relevant remains to you. Unfortunately, I strongly suspect that cutting off the D-lock removed the only working thing on that bike.

For Cherwell, maintaining editorial independence is vital. We are run entirely by and for students. To ensure independence, we receive no funding from the University and are reliant on obtaining other income, such as advertisements. Due to the current global situation, such sources are being limited significantly and we anticipate a tough time ahead – for us and fellow student journalists across the country.

So, if you can, please consider donating. We really appreciate any support you’re able to provide; it’ll all go towards helping with our running costs. Even if you can't support us monetarily, please consider sharing articles with friends, families, colleagues - it all helps!

Thank you!