Arriving at a packed-out Playhouse to see Shakespeare’s rarely performed The Two Gentlemen of Verona I had high expectations. The production marks director Sir Gregory Doran’s completion of all 36 plays in Shakespeare’s First Folio, and with a man as experienced as the former artistic director of the Royal Shakespeare Company (RSC) in charge, it was understandable that I was expecting big things.

In a speech to the Playhouse’s circle bar before the show, Doran spoke of the honour of working with students over the last academic year to put the production together. He praised their commitment, adding that five finalists working on the play had multiple exams in the week of the performances..

It was, then, a testament to this commitment that the performance was as good as it was. The production was a hilarious modern take on Shakespeare’s comedy, with several scenes updated, modified, or introduced entirely for this play. We had a drag scene, the use of Hinge (yes, the dating app), and a Formula One-themed scene to name but a few of the excellent modernisations made for this production.

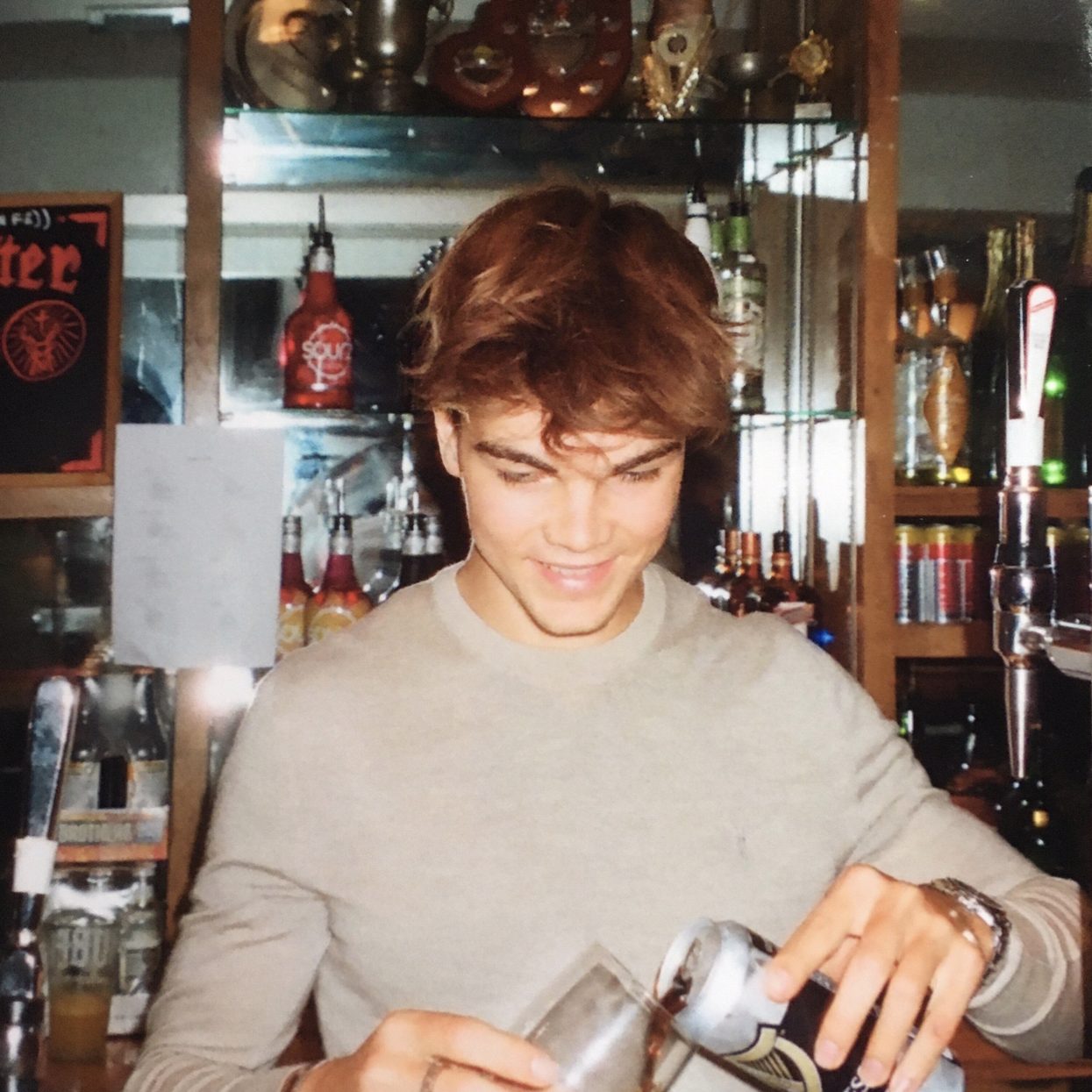

One of the stars of the show, undoubtedly, was its Duke of Milan, Jake Robertson. From his introduction in the raucous drag scene which fooled the entire audience (genuinely the highlight of the entire play), to his masterfully witty confrontation with Valentine, he had the audience in stitches throughout.

Jo Rich, playing Launce, also captured the comedy perfectly. Every scene he was part of felt like the address of a madman to his imaginary (or real) audience, and this brought his character a suitable level of chaos which matched the absurdity of the play as a whole. He also had brilliant chemistry with the live dog, Rocky, who, despite spending much of his time more interested in whatever was going on offstage, captured the hearts of the audience from his first appearance. The audible ‘awww’ when he came on for the first time was well deserved.

However, to single out individuals does not do justice to many of the cast members in this production. There are many strong performances: Lilia Kanu (Julia)’s portrayal of the heartbreak of Proteus’s betrayal, Rob Wolfreys (Proteus) in his capturing of the character as a dual figure, at times the funniest character in a scene, while at others delivering gut-wrenching soliloquies about his internal turmoil to name but a few. Also deserving praise are the servants played by Leah Aspden (Lucetta) and Jelani Munroe (Speed) whose chemistry with the lead actors was excellent.

One of the most surprising aspects of the play was the set design. Upon entry, I was underwhelmed, being greeted by nothing more than four ugly pillars of scaffolding. However, the adaptability of this set proved vital, with the production benefiting from a wide range of props which brought the set to life, while the scaffolding moved as needed to signify different settings. There was also support from a live band, which only added to the brilliance of the musical scenes.

Admittedly, on a couple of occasions, the play went too far in its unseriousness. A couple of the modifications fell slightly flat in their attempts to be funny, but these were rare and still merited a handful of laughs from the audience. All in all, the play was riotously funny, and that, in large part, is a testament to the delivery of the play by its cast.

The play also handles a difficult scene towards the end of the play well, in which Proteus attempts to force himself upon Silvia. As it ought to be, the scene is difficult to watch, and the actors did well to capture that. Will Shackleton (Valentine) and Wolfreys shine in the part in which Valentine confronts Proteus, and for such a humorous play, it excelled in its ability to switch to serious matters in an instant.

The ending of the production also held an important commentary on the play. Julia and Silvia are left on stage as the lights fade, which I took as a comment on the play’s willingness to forget the crimes of Proteus at the expense of the female characters. It was a moving signifier of their lack of opportunity to choose their paths for themselves.

All in all, The Two Gentlemen of Verona matched and furthered the expectations I held before the show. The influence of Doran was clear, but there were also aspects of the performance that were clearly student-led. This made it all the more impressive, and I hope there are more opportunities for the artistic talents of the University to work with big names and people of Doran’s level of experience in the future.