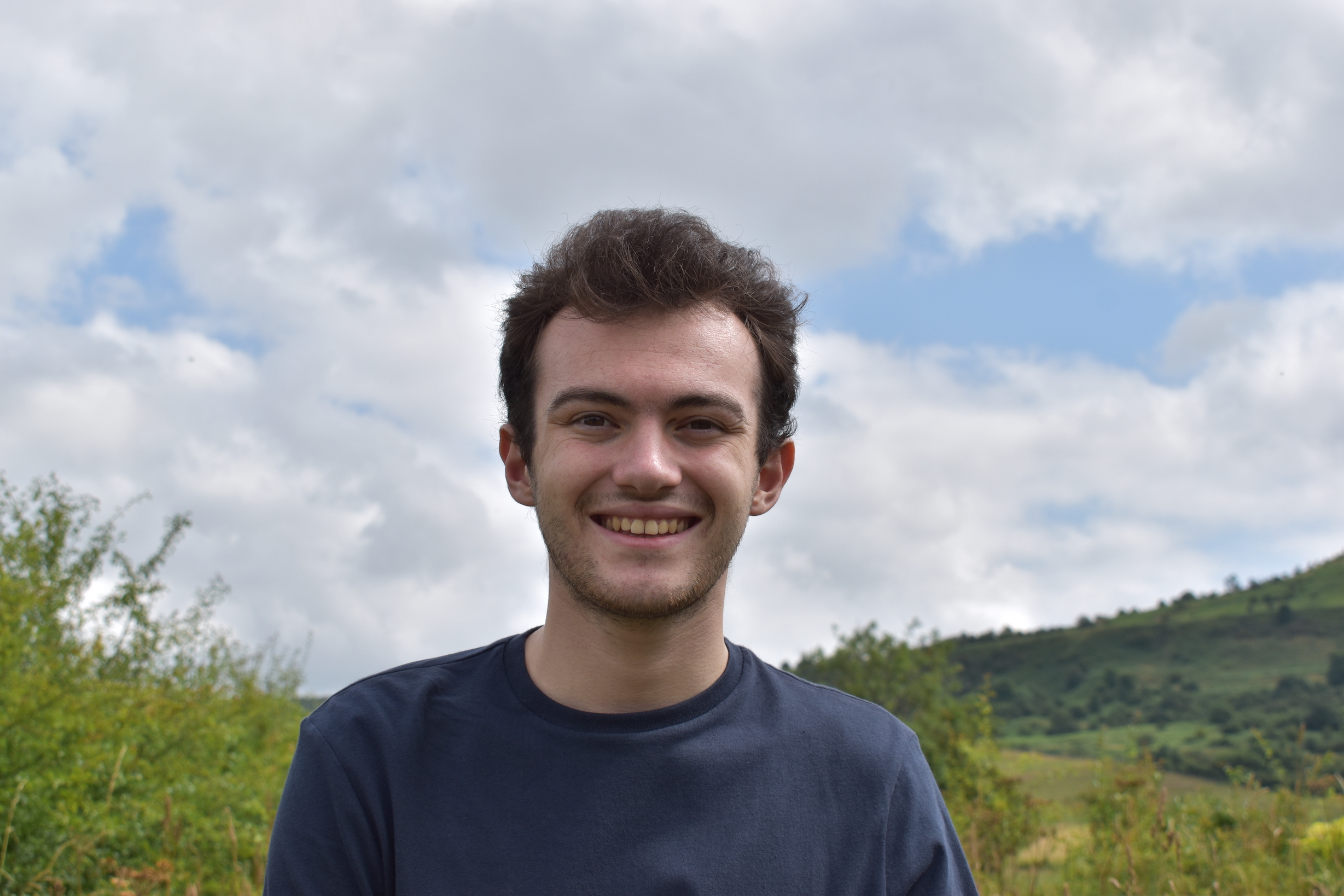

Having spent almost a year and a half in a global pandemic, I was feeling a little bereft of the ‘full’ Oxford experience and looking for a chance to see more of the University while not disrupting revision for my finals. You see where this is going.

I had rules: these had to be libraries which were open to undergraduates, without needing a special reason to study there (or, if they needed a reason, I would have to meet their requirements). This is why I wasn’t able to visit, for instance, the Weston Library.

In the process of writing this article, I felt a real sense of this university’s scale. It was a kind of travel: many of these libraries were hidden in plain sight, in buildings I’d never really given a second glance towards before. To get to the libraries themselves, I found myself traipsing through parts of the University I had no idea existed, belonging to every imaginable department, faculty, and sub-faculty.

You don’t need to go to every library on this list. But if you’re lucky enough to carry a Bod Card, you should make a point to visit at least a few. These are special places, each with its own history and personality. Make the most of them.

The Old Bodleian – Upper and Lower Reading Rooms

I remember coming here in my first year and feeling completely terrified. The Bod’s main reading rooms seem to be largely the domain of graduates and visiting scholars — the latter group, I’m told, are a hardened breed who fight tooth and nail for their Reader Cards. All of Oxford’s libraries (that I’m aware of) operate a policy of silence, but nowhere is it quite as piercing as here. Row upon row of identical desks lend this place a deeply impersonal feeling, and for such an old building, many of the rooms are weirdly sterile. Still, the views are unparalleled.

The College Library (Lincoln)

I’m told there are 44 College libraries across the University, which vary considerably in size, friendliness and academic scope. Some graduate colleges admit non-members more freely — nevertheless I was unsuccessful in my attempts to visit a few.

That said, I do think my own College’s library is one of Oxford’s best. In truth, it was one of the main reasons I applied to Lincoln. Built in the 18th century and formerly a church, the upper floor is a pleasant, airy place to either work or spend an afternoon staring at the English Baroque ceiling. The basement is a sad, dark place and I can’t think for the life of me why I spent so much of my first year down there.

Duke Humfrey’s Library

Quintessentially Oxford. That is to say, old, fussy, reasonably difficult to get into, and widely known for its idiosyncratic way of doing things (no pens and no bags, please). As an actual library, it is more show than substance: the collections it houses (which are — I kid you not — the Conservative Party archive, the University Archives and local history collections) are of little actual use to most people who use the space. The students view the place as more of a day out. Who can blame them? I’ll be the first to plaster this place all over my Instagram.

Education Library

The Education Library (not to be confused with the Continuing Education Library) is a hub for teaching and pedagogy-related texts. I’ve the impression that students from a surprisingly broad variety of disciplines find use for it (I took advantage of its modest collection of books on genocide memory, for instance). But if that’s not you, there’s a good chance it will be a little too out-of-the-way to be useful.

Like most of these smaller libraries, its real strength is its people: the librarians here were among the most friendly and helpful of anywhere in the University.

English Faculty Library

This is the Law Library’s smaller and perhaps more charming little sibling. It is located in the same building and the aesthetics are broadly the same: effortless 60s cool with an open, central atrium overlooked by a second floor. The ‘vibe’ is considerably warmer, though.

During Covid times, the EFL was one of very few libraries to allocate seats to readers — in part, I suspect, because many tables lack power outlets.

Gladstone Link

It’s often the punchline, but I’m not sure that the ‘Glink’ fully deserves the reputation it has gained in the decade or so that it’s been open as a study space.

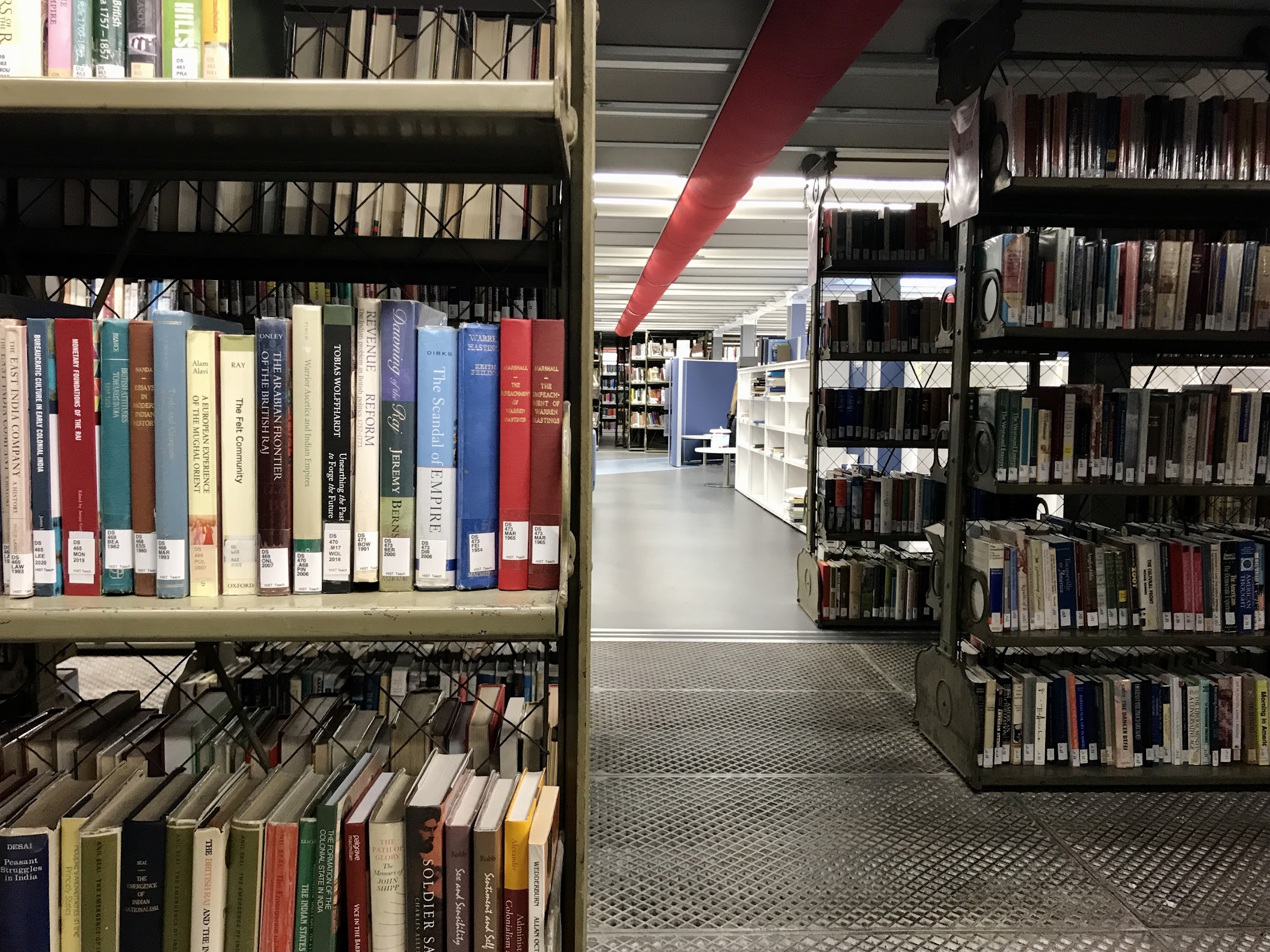

The stone staircase down from the Radcliffe Camera promises much but soon brings you to a subterranean lair with very low ceilings. (Enter from the Bodleian side and you’ll find yourself in what feels like a jet-bridge, minus the HSBC branding — or, as though you’re boarding a January flight to Tromsø, minus any promise of natural light. Sit underneath an air conditioning vent and it might feel like it, too.) If there is a redeeming quality, it would be that there is a certain charm to being sandwiched between floor-to-ceiling books on history. Do be aware that the ‘floor’ in the upper Glink is more of a metal grate: I can only imagine the number of lost wireless earbuds. Also, I can never seem to find a power outlet.

Nissan Institute of Japanese Studies Library

This is one of a number of specialised centres located around St Anthony’s College. I’m reasonably sure that it was among the first to be built at the University. The library is not a big space (at present there is room for only a handful of readers), but it is bright, welcoming, and apparently designed with Japanese architectural principles in mind. Through 2021, the construction happening next door took a little away from the tranquillity which it is usually able to boast.

While you’re at the centre, here’s a real oddity: a wall plaque unveiled by the now-disgraced Nissan car executive Carlos Ghosn in 2006, who remains a fugitive in Lebanon, having fled Japan after being arrested on charges of false accounting.

KB Chen China Centre Library

A real gem. Most students I’ve talked to don’t know that the Dickson Poon China Centre Building even exists: I’d say that discovering these obscure quarters was one of my favourite things about this challenge, but there’s nothing low-profile about this place (it also features graduate accommodation, a tearoom, a sizeable lecture theatre and teaching space, and a ‘state-of-the-art language laboratory’).

The library takes up the bottom floor, and looks out over the central courtyard: besides being home to 60,000 volumes and much of the Bodleian’s Chinese book collection, it is one of my favourite reading rooms in the entire University. It’s an ultra-modern, pleasingly designed and spacious library with both big tables and small reading nooks.

Latin American Centre Library

This library was the smallest I’d been to — it’s the former front room of a house near St Anthony’s. There’s not too much to report here: a fairly small collection of books relevant to Latin American studies. It’s reasonably cozy, with only room for a handful of students even without social distancing restrictions.

The Law Library

This is, for many of us non-lawyers, a hidden gem. The enormous main ‘hall’ of the library is bright and airy: come for the extensive collection of European and North American legal texts, and stay for the Aalto-inspired clean lines. It exudes effortless 60s style. Plus, if there’s one Oxford library to recreate on your Minecraft server, it’s this.

The library is, unusually, sponsored in part by the law firm Hogan Lovells, who were recently named and shamed for paying private investigators for intrusive surveillance in a New York Times investigation into the hand of post-Soviet governments in the English legal system. Less interestingly, it also suffers from a severe lack of power outlets (especially on the ‘open-plan’ desks).

Leopold Muller Memorial Library (for Hebrew and Jewish Studies)

The Leopold Muller is located in the basement of the Clarendon Institute, which also houses the Centre for Hebrew and Jewish Studies and the Centre for Linguistics and Philology. Though I knew the library’s brief, I don’t think I was quite prepared for the sheer size of the Hebrew book collection. It turns out that Hebrew has been taught at the University since the 16th century (the first Jewish fellow to be appointed by a College would arrive some time later, in 1882).

The librarian here was certainly a character: very helpful, and the only member of staff to catch on to my ploy of visiting all of Oxford’s libraries (or perhaps the only to ask how my adventures were going). The space, I can imagine, can become a little dreary in winter on account of it catching very little natural light.

The Music Faculty Library

If you’ve not been to the Music Faculty’s own little universe south of Christ Church, it is an experience I would wholeheartedly recommend. On the way into the library, at about ten in the morning, the door was held open for me by a figure dressed as though they were on the way to conduct the Last Night of the Proms, in full tails. It set the tone appropriately: this is an eccentric sort of place. The library itself is beautiful, but more strikingly it is charming in a Ghibli sort of way. Desks are hidden in corners, and posters plaster the walls.

Music students I’ve spoken to tell me they have a strong affinity with the Music Faculty’s librarians and the other characters sighted here. In no other library is there quite the same sense of community as in this one.

Nizami Ganjavi Library (Oriental Studies)

Nezāmi Ganjavi is widely considered among the greatest 12th century poets in Persian literature. His legacy, Wikipedia tells me, is appreciated widely across Afghanistan, Iran, and Kurdistan, but perhaps most loudly in Azerbaijan, where he is seen as something of a national hero.

Is this a library befitting such a literary giant? Not exactly. Hidden in the shadow of the Sackler Library, this isn’t likely to appear on any ‘must see’ lists — however, even in spite of its ‘town library vibes’ (as one student described it), it is not without its charms. It’s a quiet and invariably tranquil place to get work done.

The Oxford Union Library

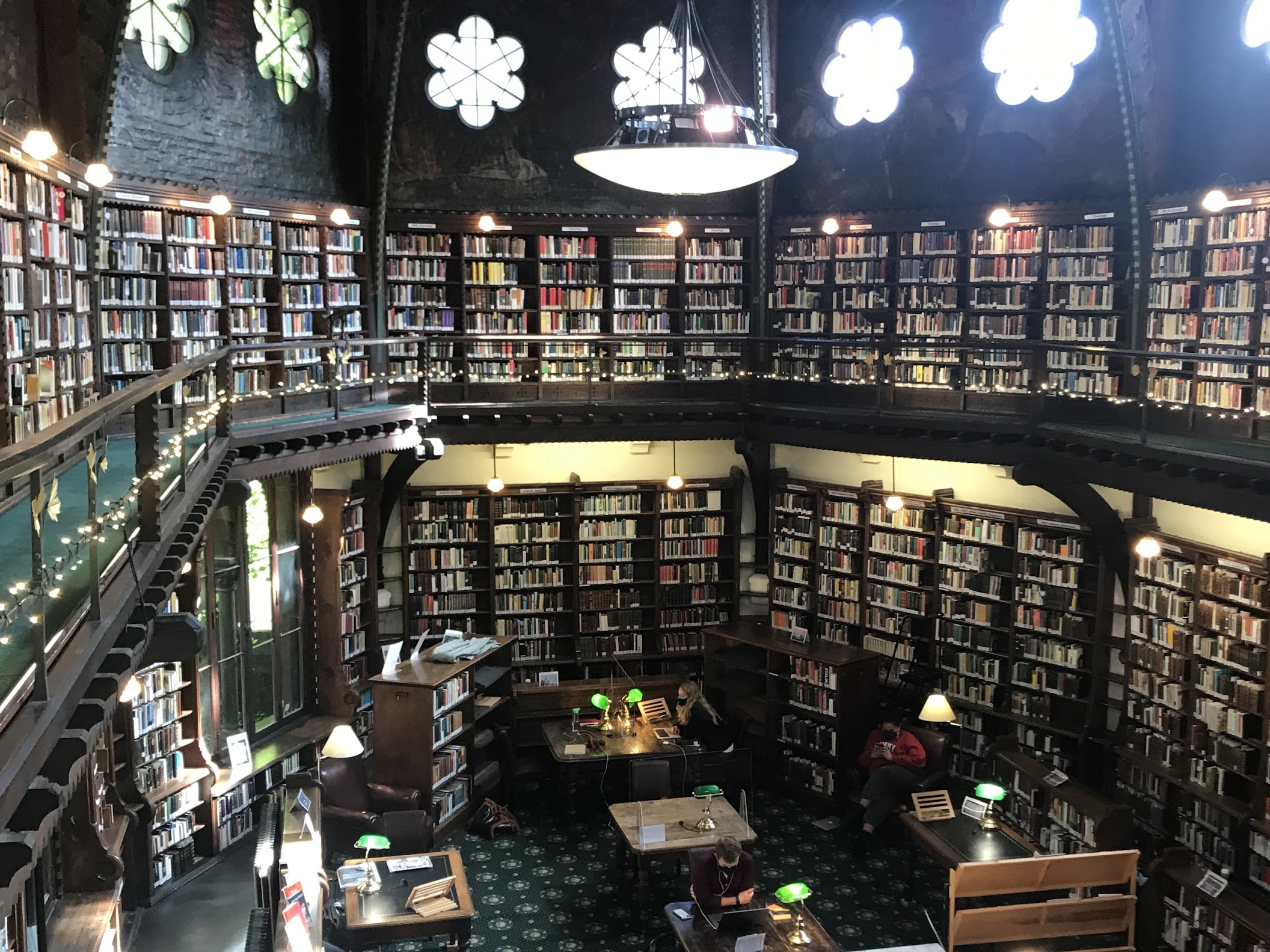

This one’s dedicated to everyone who made the mistake of purchasing membership of the Oxford Union at the start of their Freshers’ Week. It still probably isn’t worth it.

I’d always meant to study here but, then again, it was the Union so it had… all that going against it. That said, I think it’s worth spending an afternoon if you have the card. The Old Library, which was initially a debating chamber, is really quite beautiful: smaller and far cozier than the chamber across the courtyard but similar in shape. It is a comfortable and slightly sleepy place to work, decorated pretty much exactly as you’d expect. The Pre-Raphaelite ceiling murals are a particular highlight, though they’re faded and not particularly visible in daylight.

The library staff seem particularly friendly here, and the library is also noted for its nonfiction collection. Reading for fun? I might try it one day.

Oxfordshire County Library

I grew up in a part of the country that simply didn’t have the money to invest in library services. I assumed that the rest of the UK was like this, but, alas, no. The Oxford County Library is a wonderful, recently-rebuilt civic resource which is open to everyone. Though it boasts a sizable collection of books, and is an excellent place to get work done a little outside the ‘University bubble’, it is a public good that can’t be defined solely by its use as a library: it also helps people to access public services and organises events for young people across the city.

Philosophy and Theology Library

People (especially PPE students) like to dislike this one. I think their concerns are justified. Located in the otherwise STEM-oriented Observatory Quarter, this is a library over two floors — the upper being mostly a reading room — across one side of the Radcliffe Humanities Building. The space is too small to serve its purpose effectively: even in spite of social distancing restrictions, I was shocked by how busy the reading room was.

Radcliffe Camera (Upper and Lower)

The library that is Oxford. Any normal university would have the impressive but modest, modern and practical Social Sciences Library at its heart. But not us. Libraries are rarely so ostentatious or, frankly, naff. Nor are they usually so downright iconic. That we offer this hugely symbolic space to History and English speaks to the incorrect assumption that Oxford is stronger in the humanities; many students don’t realise that it spent most of its early years as a scientific and medical library.

The Upper Camera is a space best visited early on a clear winter’s morning: the sunlight streaming through the windows is quite a thing to see. But at any time, it is a beautiful place to work. The silence here isn’t quite as oppressive as in other study spaces — perhaps on account of the number of giddy undergraduates living out their Dark Academia dreams.

Rewley House Continuing Education Library

A library I didn’t know existed, serving 15,000(!) enrolled students at the Department of Continuing Education. I imagine most students don’t realise ContEd has a history here that stretches back to the late 1800s. At the heart of the operation for the last hundred-or-so years is Rewley House, a building on Wellington Square that I’d not paid much attention to before. The library looks out over a courtyard, and is probably unusual in housing a small number of texts on an extremely wide range of subjects (plus an extensive reference collection).

The Classics Library (The ‘Sackler Library’)

I’d always resented that one of our libraries was named for the Sackler family, who grew extraordinarily wealthy by playing an important role in causing the opioid crisis (which, in turn, contributed to nearly 400,000 deaths from drug overdoses from 1999 to 2017 in the U.S.). It is one of many projects to which the Sacklers have lent their name — others can be found in the Guggenheim and the Met in New York, and the British Museum and the V&A in London.

But then I visited. If the Sacklers had to give their name to a library in this city, I’m almost relieved it’s this one — one of Oxford’s ugliest and least liked by readers. The architectural style can be best described as ‘McMansion’. The floors of the central rotunda are disorientating and lacking in natural light. Neoclassical columns, which again scream ‘GOP Congressman’s Florida mansion’ more than ‘world’s largest and possibly oldest Classics department’, are awkwardly shunted into the architecture as though the building is desperate to remind you what purpose it serves. Unless you need to access anything from the collections held here, it is probably a library best avoided.

Social Sciences Library

The Manor Road Building, which houses the SSL on its ground floor, feels in many ways like a 21st century response to the 60s Internationalist St Cross Building next door. Both are wonderful and underrated, but the Manor Road Building still (having been open now for nearly twenty years) feels like a model for future university spaces. It’s light, airy and clearly designed to invite collaboration. It is an ethos that continues into the library itself, which features many sorts of workspace, including open-plan desks, booths, and workrooms. It fosters an excellent working environment that is spacious, bright and clean. The resources available cut across far more disciplines than I could hope to name here.

My one criticism? It’s always a little too warm. Other than that, it comes highly recommended.

Taylor Institution Library (Taylorian)

The Taylorian specialises in modern languages. It was built as the east wing of a complex which includes the University Galleries (now the Ashmolean), and extended twice in the 20th century. Other parts of the Institution provide space for talks and lectures.

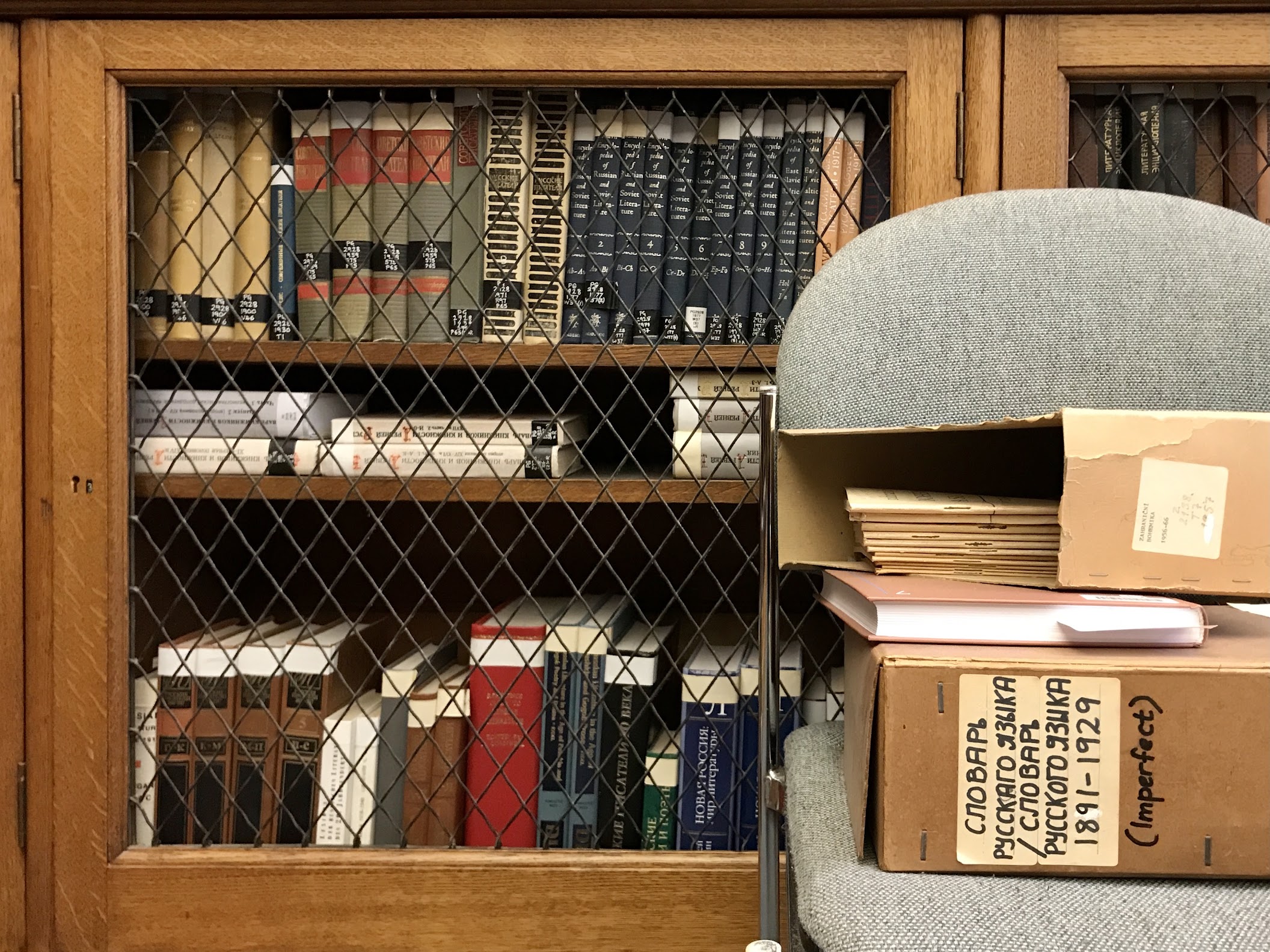

I’m not certain if this is usually the case, but I’ve not once been able to find a space in the library’s iconic neoclassical main reading room on the first floor (in our current times of social distancing, at least, you must be first in the queue to have any hope of studying there). Usually this has meant that I’ve been relegated to the library’s side-rooms (the sort which specialise, for instance, in Slavic languages), which are nonetheless smallish, pleasant spaces with high ceilings.

Vere Harmsworth Library (for American Studies)

Among the best, the Vere Harmsworth comes last. This is an ultra-modern library that completely nails it. Continuing the long-established Oxford tradition of naming buildings after people who, to greater or lesser extents, are hardly role models (see the Sackler, Rhodes House and the Thatcher Business Education Centre at the Said Business School), this one is named for the man who created the Daily Mail in its modern form.

Frankly, it’s a name unbefitting. Across four levels, it’s a clean and light space that benefits from not feeling bewilderingly large. Seating is available in open-plan desks, individual desks and booths. My favourite time to be here is late at night, an hour or so before closing time, when the outside of the building is beautifully illuminated from the ground and the huge glass windows reflect the interior. Simply put, it’s a cool space.

Image credits: Edward Rhys Jones.