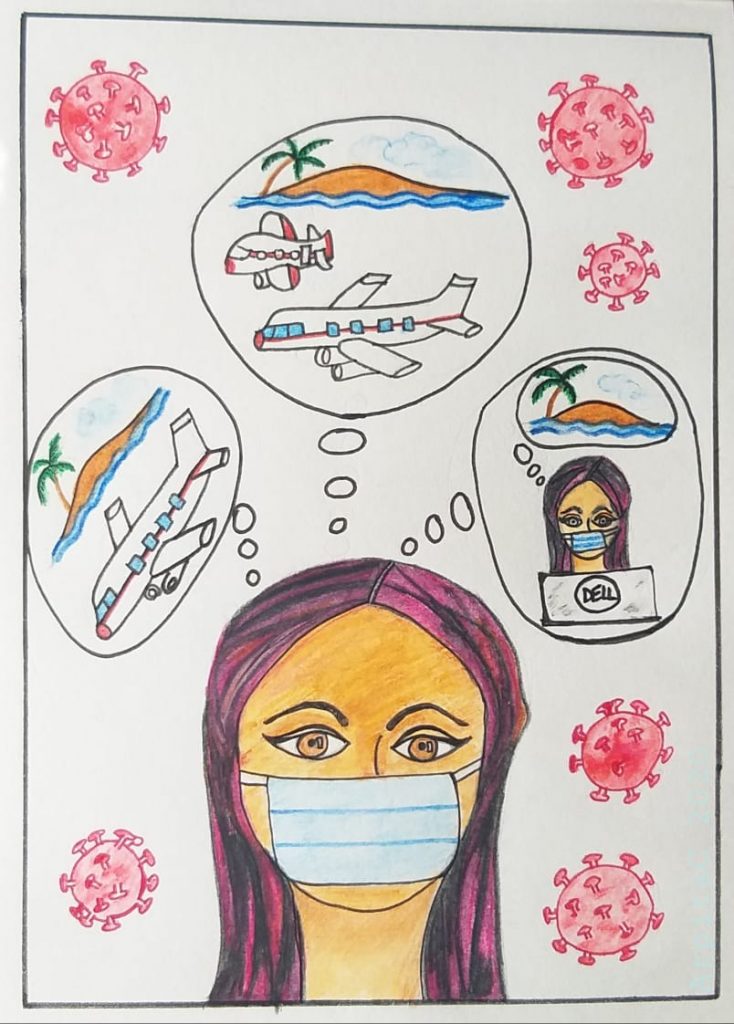

As international tourism reopens, an important question is back on the cards: should we fly? If we want to be responsible travellers, this is the fundamental question each of us must answer.

Throughout 2019, as the media feverishly covered Greta Thunberg’s transatlantic voyage, this question filled me with cognitive dissonance. Not flying seemed ascetic and impractical, exuding a perverse privilege of time and money, and yet it also seemed to be the only ethical solution in sight. Was anything else hypocritical? What opportunities to learn and experience the world would I forgo in a decision not to fly? Would my decision make any difference to the climate anyway? The dissonance deepened the more I wrestled with it.

But dissonance is an insincere position. I believe we have a moral obligation to confront such issues head-on, to educate ourselves into a stance, however nuanced that stance must be. The coronavirus pandemic and the Black Lives Matter movement both helped me arrive at a position, offering clarity on questions of environmental justice and the interplay of individual and structural decisions. Tragically, the coronavirus pandemic has given us a view of what a world without air travel might look like. I want to share, in long-form, the research and reflection which have brought me to a decision.

***

My first step towards an answer was assessing commercial aviation’s contribution to climate change. Before the pandemic, the aviation industry was responsible for somewhere between 4 and 5% of total human-caused global warming. About 40% of this warming came from CO2 emissions, representing 2.4% of global fossil fuel emissions in 2018. The other 60% of the warming came from gases like nitrogen oxides and sulfur dioxide, tiny particles like sulphate and soot, and changes to cloudiness induced by these particles.

Aviation-induced cloudiness may account for up to 55% of the total warming impact from aviation. At temperatures below -40oC, soot and tiny water vapour droplets ejected from aircraft engines act as nuclei onto which ice crystals can form, producing a white line of clouds behind the aircraft. These are the striking condensation trails (‘contrails’) familiar from the ground, which are subsequently dispersed by winds into thin, hardly visible ‘contrail-cirrus’ clouds. These clouds reflect very little solar radiation but insulate like other clouds, making them potent warming agents.

Despite representing the majority of current global warming from aviation, these non-CO2 sources are hardly mentioned in media debates about flying. Part of this is because the best estimates for contrail extent are more uncertain than those for CO2 emissions; measuring such thin, short-lived clouds from satellite data is far harder than calculating CO2 emissions directly from the amount of fuel burnt, and so industry and media publications frequently err on the side of caution. Uncertainty is integral to robust science but is exploited by fossil-fuel industries to hide the knowledge that this warming exists, is large, and needs to be addressed.

A second reason for the omission is related to the different timescales over which warming effects operate, and the difficulties in jointly assessing them. For instance, contrail-cirrus clouds from an individual aircraft persist and contribute to warming for at most a day, whereas CO2 emissions accumulate and contribute to warming over centuries. In other words, CO2 emissions from the first trans-Atlantic flight in 1933 are still warming the Earth, but only yesterday’s contrails are. Nonetheless, because contrails are so potent at locally warming the atmosphere, the typical daily extent of contrails induces more warming than “all the aviation-emitted carbon dioxide that has accumulated in the atmosphere since the beginning of commercial aviation” causes on that day.

The coronavirus pandemic illustrates this nicely. In areas where aircraft fleets were grounded, no warming could come from contrail-cirrus, but warming was still being contributed by the legacy of past aviation CO2 emissions. However, the virtually instantaneous climate response to contrail-cirrus should not lead us to underestimate it – as soon as we start flying again, contrail-cirrus will resume; its extent is expected to triple by 2050, growing at a faster rate than CO2 – but it does explain why CO2 and non-CO2 warming are so often separated.

A third reason why non-CO2 warming is often forgotten is its non-linearity: altitude, latitude, temperature, time of day and the characteristics of the land beneath the flight path (that particulates fall onto) all determine the magnitude of the non-CO2 warming components. This precludes being able to specify ahead-of-time the precise warming contribution of a given flight. Unfortunately, favourable conditions for airline efficiency are those that exacerbate contrail warming – such as flying at high altitudes, high latitudes and at night (because there is no reflection of solar radiation to partially offset the warming at night).

Many carbon calculators and media visualizations suggest we can address the non-CO2 warming contribution simply by multiplying CO2 emissions by two. The three factors discussed above (measurement uncertainties, temporal disjunctures and non-linearity) explain why this approach is flawed. (This is a mistaken interpretation of a ratio known as the relative forcing index, which divides all past aviation emissions contributing to warming today by all past aviation-CO2 emissions contributing to warming today). We cannot use this ratio in any predictive or multiplicative way for an individual flight. Hence, it is incredibly difficult for scientists to robustly calculate aviation’s ‘total global warming potential over the next 100 years’, the standard metric used in international agreements to specify how much global warming an individual action will have.

Going through these technical details is important. Firstly, they highlight how the aviation industry exploits legitimate measurement difficulties to trivialize itself and escape international regulation under the Paris Agreement by only referencing CO2. Secondly, measurement uncertainties and non-linearity together explain why most flight carbon calculators will probably underestimate the damage of a given flight. Thirdly, the inherent unpredictability of a flight’s climate impact shows why waiting for better technical data does not excuse current inaction.

In short, we need to consciously acknowledge all the possible warming effects of flying in our decision-making, even if an accurate picture of the climate impact of a given flight is unknowable until after the plane lands. Most simply, the bottom line is that 5% of global warming was caused, pre-pandemic, by commercial aviation.

The next important topic to investigate is the uneven distribution of air travel, even within richer nations like the UK. In 2019, less than half (48%) of the UK population flew (weighted towards London and the south-east), and yet the UK still had the third largest aviation emissions of any country. The 15% of the UK population who fly three times or more a year take about 70% of all UK flights, flights which have been laid at the door of second homes, offshore tax havens, and frequent short-haul city breaks. Flights per capita are highest for wealthy island nations and offshore tax havens.

Globally, inequality in aviation is far more extreme. Although the proportion of the global population who have ever flown has never been systematically addressed (which is itself telling), somewhere around 6% is the current best guess. Airline routing shows that only 1.2% of the total carbon emissions of air passengers were emitted for flights between African countries in 2018, whereas 18% was emitted between North American destinations (over a far smaller geographical area). Research by Oxfam demonstrates that the richest 10% of the world’s population emit 49% of all CO2 emissions. Air travel is even more unequal: the top 10% consume 75% of all air-transport energy.

Fly from London Heathrow to JFK New York and back and you’ve already emitted more CO2 than the average person in 56 (mostly African) countries emits in a year, according to an uncomfortable Guardian visualization – and this calculation ignores non-CO2 warming effects. I recommend having an experiment with the page: I found it an incredibly powerful visualization because it fully highlights the environmental racism and the environmental privilege involved in flying.

Indifference to carbon inequalities and disregard for climate change’s disproportionate burden on people of colour is a form of racism, according to Laura Pulido, a leading scholar in the field. “The evidence for the uneven and unfair distribution of death [from climate change] is overwhelming”, she writes. “Indifference…characterizes the attitudes, practices, and policy positions of much of the Global North toward those destined to die”. Pulido discusses environmental racism as structural, state-sanctioned racial violence that has always been inherent to capitalism, and that has always offloaded its externalities onto poorer, less valued bodies.

Environmental privilege is the ability to reside in (and travel to) clean, un-poisoned places, shielded from climate change’s worst impacts, all the while polluting the environment. In the words of social activist, Naomi Klein, environmental privilege requires vast sacrifice zones. “Fossil fuels…are so inherently dirty and toxic that they require sacrificial people and places: people whose lungs and bodies can be sacrificed to work in the coal mines, people whose lands and water can be sacrificed to open-pit mining and oil spills…And you can’t have a system built on sacrificial places and sacrificial people unless intellectual theories that justify their sacrifice exist and persist: from Manifest Destiny to Terra Nullius to Orientalism, from backward hillbillies to backward Indians…[It’s] the original Faustian pact of the industrial age: that the heaviest risks would be outsourced, offloaded, onto the other – the periphery abroad and inside our own nations.”

I believe the Black Lives Matter movement must be a clarion call for people who fly and have flown to examine the privilege of choosing to fly, something I’m guilty of not doing in the past.

The first authors to use the term ‘environmental privilege’ remark that those with it “often believe they have earned the right to these privileges”. Yet how can anybody earn a right to fly and emit a vastly outsized share of emissions, way above the global per capita emissions necessary to keep climate change under control? To me, it is essential to reframe flying not as a right or a goal but an immense privilege and responsibility. Not flying is not about victimhood or sacrifice but the position of the great majority of the world’s population. Prominent environmental activist and journalist George Monbiot captures the mood well: “these privations affect only a tiny proportion of the world’s people. The reason they seem so harsh is that this tiny proportion almost certainly includes you.”

Are there, then, any arguments that can justify buying a holiday plane ticket, when to buy one is the most damaging single action for the climate most people can make? This is where I feel the coronavirus pandemic offers clarity. It has given climate activists, tragically, the very result they were campaigning for. We no longer have to talk hypothetically.

Aviation is the backbone of tourism: about 60% of international tourist arrivals are by plane, not to mention domestic travel. Much of tourism’s recent growth comes from the 60% decrease in airfares since 1998, with most tourists now travelling for leisure, not business. Tourism is not a marginal sector: it represented 10.3% of the world’s GDP in 2019, and has been crippled by the pandemic; the World Travel and Tourism Council expects 31% of tourism jobs (100.8 million) to be lost in 2020. The last four months evidence the merit in the argument that some air travel is necessary for development and cultural exchange. If not, are we happy with the prospect of swathes of the travel industry collapsing again? Of course, this is a slippery, ethically complex issue: the same countries most vulnerable to sea level rise are most dependent on tourism and international aviation for income. Whilst I would love to see the scope of both long-haul and short-haul flights curtailed, the crucial takeaway for me is that abstention from flying can be socially and economically destructive, just as climate change is.

The pandemic has also brought into sharp relief the structural reasons limiting the effectiveness of individual action. By April, although passenger numbers had fallen by over 95% worldwide, CO2 emissions from aviation had only fallen by 60%, fitting with the 62% decrease in flight departures. In other words, many flights have been taking off practically empty: ‘ghost flights’.

There are several reasons for this. Firstly, in the US, a stipulation for government bailout was that airlines kept routes running despite the low demand. This emphasizes how important regional interconnectivity is for governments and their unwillingness to axe major transportation routes for the climate’s sake. Secondly, ghost flights flew because of slot allocation rules (until these were temporarily suspended). Slots are the ability for an airline to take off and land at crowded airports at particular times, reallocated every six months. If an airline operates its slots at least 80% of the time (the ‘use it or lose it’ rule), it can keep the slot for the following season, making them ridiculously valuable at busy airports. For instance, Oman Air reportedly paid US$75 million for a pair of Heathrow slots in 2016 and British Mediterranean Airways flew a plane empty six days a week for six months to Cardiff in 2007 to preserve its Heathrow slot after axing a route to Tashkent.

The pandemic reveals how far airlines are incentivised to fly popular routes regardless of their passenger load factors. A major argument of the Swedish flygskam (flight shame) movement is that aircraft departures could be reduced if enough people abstained from flying. Whilst passenger numbers fell in Sweden in 2019, these reductions were crucial to small regional airports without slot allocation; there is a sense of futility to the consumer-driven argument. It would be crazy for airlines to give up their expensive slots at crowded airports when the aviation industry was expected pre-pandemic to more than triple in size by 2050. Even if businesses and academia continue videoconferencing and many airlines are laying off pilots and old stock, air travel is still likely to bounce back. Therefore, the main challenge for climate activists is to stop further expansion and further lock-in. This is why the court ruling that deemed Heathrow’s third runway illegal was so important.

Aviation is also artificially cheap. Although part of this is budget carriers and record-low oil prices, cheapness is also structural. Article 24 of the 1944 Convention of International Civil Aviation exempts all aviation fuels from taxation. According to a 2019 government briefing paper, this is an “indefensible anomaly”, but it is an anomaly that the UK government can do little about. Whilst Article 24 exists, any fuel taxation policy would only encourage environmentally damaging ‘tankering’: filling up a plane as full as possible in a non-taxed jurisdiction, leading to more emissions due to the plane’s heavier weight. All progressive aviation regulations – such as a no-fly zone over the Arctic – face the Sisyphean challenge of obtaining unlikely worldwide cooperation.

However, I believe it is disingenuous and dangerous to meekly accept that individuals cannot change commercial aviation’s fate. We might not be able to stop pre-coronavirus flight levels resuming, but our choices can slow the industry’s rate of expansion, particularly as role models like Greta Thunberg shift the representation of aviation away from discourses of freedom and status towards recognition of damage, privilege and death, including flying’s toll on personal health.

PhD researcher Steve Westlake has shown that “around half of respondents who know someone who has given up flying because of climate change say they fly less because of this example.” Another study shows climate scientists with smaller carbon footprints are believed as more credible by the public. Credibility increases as communicators reform their behaviour. Crucially, individual action also paves the way for public acceptance on structural changes, like taxes on frequent fliers.

As leading no-fly climate scientist Kevin Anderson puts in: “individuals are what we first see manifesting potential systemic change. To succeed, examples of change need to gain momentum, be taken up by others, and finally be scaled up – perhaps through top-down nurturing and the development of specific policies.”

Ultimately, I admire people with lifelong no-fly policies, but I think being puritanical and renouncing flight should not be the focus of the discussion, as the pandemic has shown. Widespread reduction is what we need, not individual or societal elimination. Alongside the massive privilege of flying, there is the privilege of being able to choose not to fly, a privilege afforded by fast, dense train networks; by powerful passports which minimise overland visa hassles; and by family living close to home. If those privileges are available to us, I think we should take them to minimize our harm, but if they are not available, we should not shame occasional flying.

***

So, here is my decision. I aim to take at most one personal flight in the next three years. If I fly, I will commit to maximising my time at the destination and will spend my money at homestays and local businesses. I will try to fly medium-haul (the least carbon-intense distance per kilometre); economy-class on the most efficient planes; in the morning (to minimise contrail-cirrus warming); with minimum luggage; and not through the Arctic, where aviation is especially devastating. I have come to see the higher price of train fares as the fair price I should pay to minimise the emissions travel causes. Rather than offsetting through an offset charity-cum-business, widely regarded as ineffective (see here for concise summary), I will donate to a dedicated forestry charity (like treesforlife.org.uk) where concerns about additionality, permanence, leakage and enforceability are less pronounced.

***

I hope my article helps you think through this complex issue – writing it has certainly helped me. Let’s have a conversation that avoids flight-shaming and which learns from the Black Lives Matter movement and the coronavirus pandemic. Let’s be nuanced and self-reflexive rather than allowing ourselves to wallow in dissonance.